Tenderloin

Essay

In the final decades of the 1800s, a vice district emerged just north of Philadelphia’s city center. Bound by Sixth Street on the east, Thirteenth Street on the west, Race Street to the south, and Callowhill Street to the north, this neighborhood was called the Tenderloin, like similar districts in many other cities of the era. The Tenderloin, encompassing Philadelphia’s cheap amusements district as well as its tiny Chinatown, housed as many as 250 pool rooms, gambling resorts, saloons, opium dens, and brothels by the close of the nineteenth century.

The origin of the nickname “Tenderloin” is unclear, but newspaper articles from the late 1800s note that red-light districts—areas with concentrated commercial sex and vice enterprises—offered “prime cuts” for multiple constituencies: sex, drugs, and amusements for the working classes; good incomes for madams, pimps, and showmen; and graft opportunities galore for politicians and police officers.

As in other cities, Philadelphia’s Tenderloin developed at the edge of the growing central business district (then extending westward along the axis of East Market Street) and in the vicinity of new railroad stations (the major depot for the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad built in 1859 at Broad and Callowhill Streets and its replacement, Reading Terminal, on Twelfth Street between Arch and Market, in 1893). The shifting market functions of the city center produced change for the neighborhood once occupied by prosperous merchants. As the railroads made it possible for the professional classes to move to suburbs like Chestnut Hill and the Main Line, the district they left behind became home to wholesale and retail warehouses, tenements, stores, single-family houses, and furnished-room houses (high-density homes offering lodging to single people). An abundance of inexpensive housing attracted a new population of working-class Chinese and European immigrants as well as African Americans. Low rents and the proximity to the railroad depots created a venue for vice as well as quick access for visitors to the district’s dime museums, brothels, and vaudeville shows.

Tenderloin Amusements

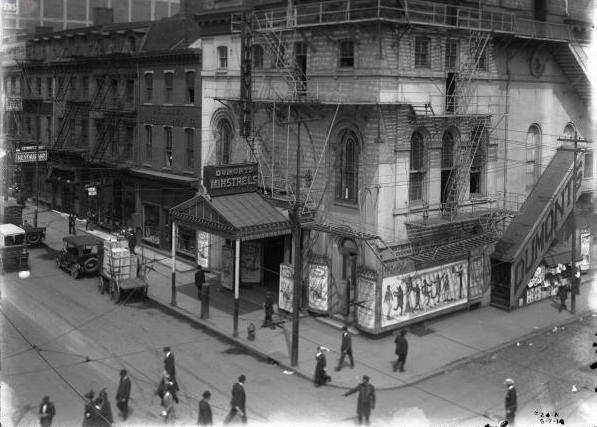

The Tenderloin’s more unseemly offerings sprang up next to the district’s working-class entertainment options: minstrel shows, dance halls, and circus performances. On one block of Eighth Street, between Arch and Vine, three vaudeville theaters—including the Bijou and the Fourpaughs—emerged between 1875 and 1895. By 1910, this block contained five movie houses (in addition to the three vaudeville theaters), two dime museums, five shooting galleries for recreational target practice, and numerous other cheap diversions like penny peep shows and palm-reading parlors. A sociologist who surveyed the Tenderloin reported in 1912: “The tenderloin theatres are not composed entirely of degenerate residents of the slums, of wicked gamblers, of ‘furnished roomers,’ and painted blondes of doubtful virtue.” He conjectured that without the patronage of people passing through the city and others visiting from the suburbs and country, more than half of the Tenderloin’s theaters would fail. He also pointed to the district’s inexpensive housing stock, a plethora of low-cost rooming houses that furnished chorus girls and actors with temporary shelter and board.

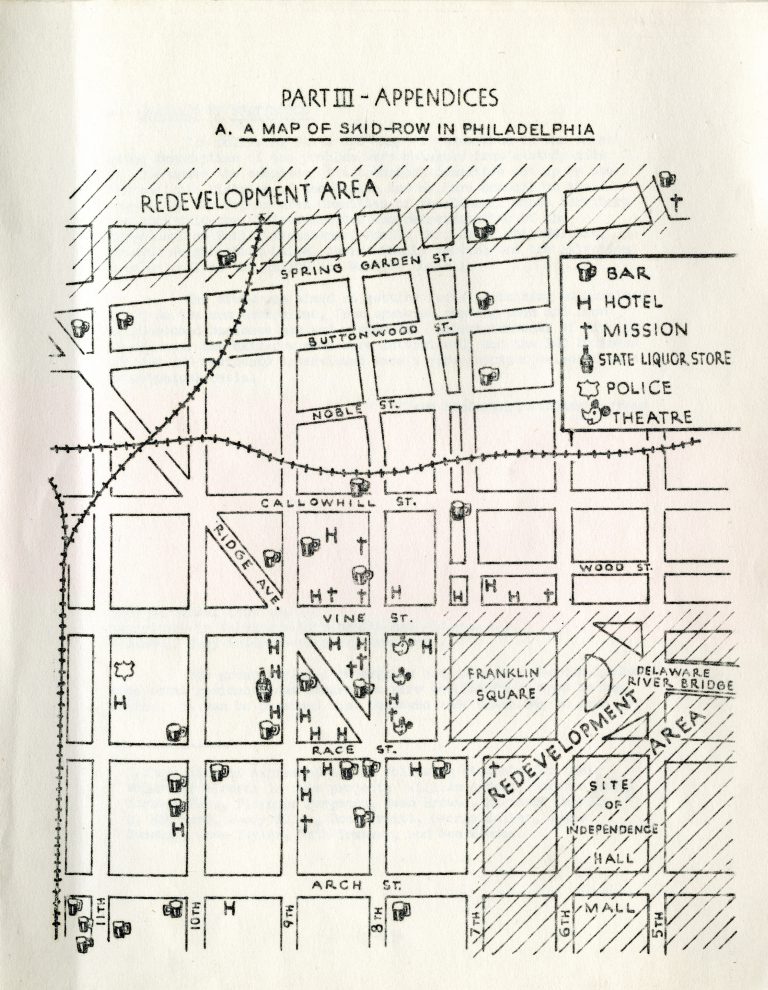

The eastern outskirts of the Tenderloin and the warehouse district stretching east to the Delaware River attracted a Skid Row population of poor, homeless, and transient men and the missions, saloons, flophouses, and cheap restaurants that catered to them. This population, like the working classes, was drawn to the Tenderloin because of its inexpensive housing options and its proximity to the city’s rail yards and labor opportunities.

The abuse of opium, morphine, and cocaine ran rampant in the Tenderloin. By 1910, Americans consumed 68,000 pounds of opium annually, with many of the nation’s Chinatown neighborhoods facilitating the drug’s trade. The recreational use of opium had existed in China for centuries, and many Chinese immigrants brought a tradition of opium smoking with them when they arrived in the United States. Chinese immigrants settled the 900 block of Race Street in the 1870s and 1880s. The concurrent emergence of the Tenderloin around Chinatown ensured that opium dens catering to a Chinese clientele found new patrons of differing ethnic and racial backgrounds. During one midnight raid on Chinatown’s opium dens in 1900, Philadelphia police arrested more than forty Chinese-Americans, along with white and black men and women.

The Politics of Vice

Though police disrupted illegal activity in the Tenderloin, the press noted a pattern of inconsistent law enforcement in the district. Newspapers and reformers had long observed connections between the city’s political machine and its most well-known vice district. In a 1905 editorial in the Philadelphia Inquirer, the Rev. Daniel I. McDermott, rector of St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church, claimed that the machine had “made a Sodom out of the heart of the city” by regulating vice in the Tenderloin. Many of the district’s “dens of infamy” remained operational by bribing local police officers and paying tribute to the Republican political syndicate. McDermott chided the police and the mayor, asking what right they had to “dedicate a section of the city to debauchery, to make it a plague spot, to scandalize its residents, to imperil the virtue of its youth and depreciate the value of property.” A grand jury investigating the Tenderloin echoed McDermott’s sentiments and went even further, blaming the prevalence of “disorderly houses” (brothels) not only on police graft and political interference, but also on the leniency of the courts. Many prostitutes simply saw their court fines as licensing fees.

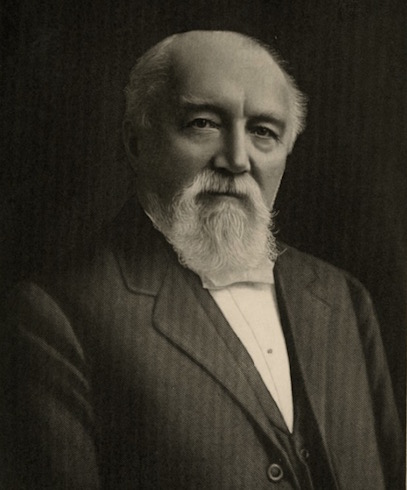

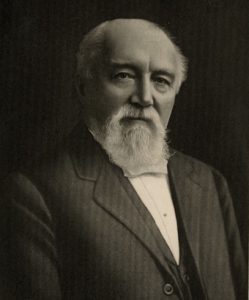

To attack the social evils of the Tenderloin, reformers sought to dismantle the Republican political apparatus from the top down. They rallied around Rudolph Blankenburg (1843-1918), who became mayor of Philadelphia in 1911 after what the New York Times later called “one of the greatest reform campaigns ever fought in this country.” Blankenburg—a rarity as a reform-minded Republican within a then-unscrupulous party—appointed a Vice Commission, which uncovered a thriving market throughout the city for commercial sex, gambling, and drug use. The investigators found the largest number of vice houses in the Tenderloin (the city’s sixth and eighth police districts), which accounted for much of the $6.2 million spent on prostitution per year in Philadelphia. Three-quarters of all the city’s arrests for streetwalking (prostitution solicitation in the streets) took place in the Tenderloin.

Like other Progressive-era reformers, Blankenburg believed vice to be a social evil requiring treatment similar to contagious diseases. The social contamination caused by vice, they reasoned, required quarantine and suppression. This segregationist approach to vice differed from two other common approaches to combating vice in this era—the first involved licensing and regulation, while the other, referred to as “abolition,” required constant repression until annihilation was achieved.

Although Blankenburg may have leaned toward a segregationist approach, neither he nor the Vice Commission considered the Tenderloin to be a segregated district because respectable people lived and worked throughout the district despite the presence of vice. Just north of the Tenderloin sat the furnished-room district, home to a burgeoning class of office workers—many of whom traversed the Tenderloin every day on their way to and from work in Center City. If not entirely segregated, the Tenderloin occupied the space of de facto red-light district in the city’s popular imagination, thanks to regular media coverage of the district’s seamy character.

The Tenderloin became a site of spectacular police raids, open-air political stumping, and missionary moralizing. In 1910, more than fifteen hundred religious reformers marched into the Tenderloin from City Hall on a Saturday evening, intent on interrupting the vice trade and focusing press attention on the city’s underbelly. In the wake of the 1913 Vice Commission’s investigation, Mayor Blankenburg took a walking tour of the Tenderloin, and within the span of four blocks, hundreds of onlookers had joined him for an excursion through the neighborhood. Although Blankenburg declared in 1912 that vice was “practically eliminated” in the city, and again in 1915 that “the much-heralded ‘Tenderloin’ does not exist,” vice squads continued to locate and interrupt illegal activity. During a single night in July 1916, police arrested more than five hundred people. Critics claimed that highly publicized raids and marches drew unnecessary attention to the red-light district while at the same time displacing vice onto other neighborhoods.

The Decline

As in many other red-light districts across the country, the Tenderloin’s sex trade declined around 1920. The United States’ entrance into World War I in 1917 introduced a marked national effort to repress vice and promote healthy living among servicemen. Police clamped down on districts like the Tenderloin, and in Philadelphia vice migrated to the main commercial thoroughfare, Market Street, where department stores and motion picture houses drew men and women from a variety of backgrounds for work and pleasure. Changing gender norms, economic opportunities, and the massive federal apparatus of Prohibition also shifted the landscape of vice by pushing drinking culture and its attendant behaviors further underground.

Architectural interventions further disrupted the neighborhood’s identity. The 1926 opening of the Delaware River Bridge (later renamed the Benjamin Franklin Bridge) led to more traffic around Franklin Square—the eastern boundary of the Tenderloin. By the mid-1900s, as commercialized vice disappeared from all but a few pockets of the Tenderloin, the former red-light district became known as Skid Row, as a longstanding homeless population continued to inhabit the neighborhood. The late-twentieth-century building of the Vine Street Expressway through the exact center of the former Tenderloin shifted the character of the Skid Row and Chinatown neighborhoods even more. A destination for pleasure seekers and a home to many working-class people in the late 1800s and early 1900s, the former Tenderloin became simply a place for commuters to pass through on their way elsewhere.

Annie Anderson is the senior research and public programming specialist at Eastern State Penitentiary and the coauthor, with John Binder, of Philadelphia Organized Crime in the 1920s and 1930s (Arcadia Publishing, 2014). She received her M.A. in American Studies from the University of Massachusetts Boston. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Prostitution in Philadelphia: Arrests 1912-1918 (Stanford University)

- The Rise and Fall of Blackface Minstrelsy in The City of Brotherly Love (The PhillyHistory Blog)

- The Skeleton Man, the Jersey Devil and a Multitude of Other Attractions (The PhillyHistory Blog)

- The Trocadero Theater (VisitPhilly.com)