Whiskey Rebellion Trials

Essay

The first two convictions of Americans for federal treason in United States history occurred in Philadelphia in the aftermath of the Whiskey Rebellion, an uprising against the federal excise tax on whiskey that took place primarily in western Pennsylvania in 1791-94. Philadelphia served as the nation’s capital during this period and therefore was the city in which the excise legislation was passed, where President George Washington (1732-99) issued his proclamations against the rebels, and where the trials for a number of the rebels took place.

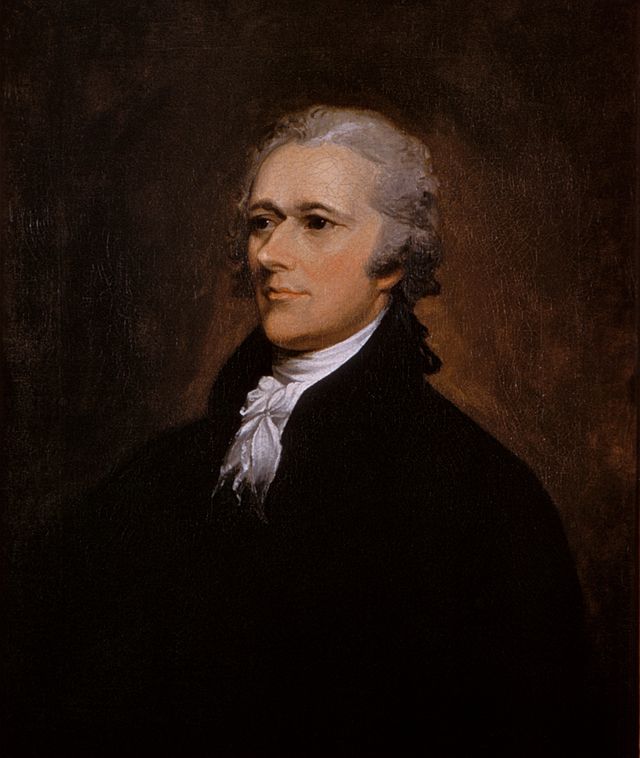

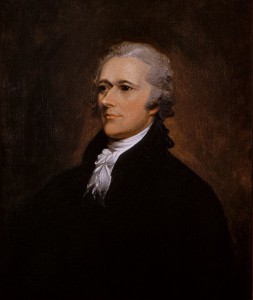

The Whiskey Rebellion developed after the First United States Congress, seated at Congress Hall at Sixth and Chestnut Streets, passed an excise tax on domestic whiskey on March 3, 1791. This legislation, pushed through Congress by Secretary of Treasury Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804), was designed to help pay off state debts assumed by Congress in 1790. The law required citizens to register their stills and pay a tax to a federal commissioner within their region. Almost immediately, protests flared in areas such as North Carolina, Kentucky, and particularly western Pennsylvania. Citizens on the frontier protested because they had little money to pay the tax and had used whiskey to barter within their regions for decades. Secondly, they thought that the tax opened the door for government intrusion into their domestic lives, which they believed Americans had fought against during the American Revolution.

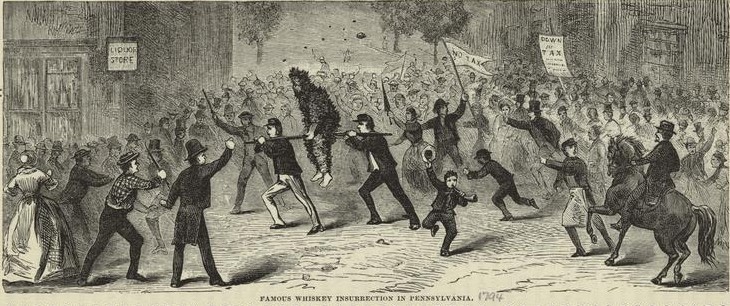

The first resistance to the excise tax in western Pennsylvania occurred in September 1791 when sixteen men assaulted an excise collector in Washington County by cutting his hair, tarring and feathering him, and leaving him in the woods. Protests continued through 1791, although they were not always violent. Citizens also organized mass meetings in July and September 1791 to draft petitions to Congress to repeal the tax. Western Pennsylvania then remained relatively peaceful until the fall of 1792, when John Neville (1731-1803), the regional supervisor for the collection of the federal excise tax, rented an office from a local man named William Faulkner. Within days, roughly twenty men ransacked Faulkner’s home and forced him to swear an oath to evict Neville, which he promptly did. Partly in response to this attack, but more importantly due to overall resistance to the excise tax, President Washington issued a proclamation condemning the excise resisters on September 15, 1792.

Despite this federal proclamation, resistance continued into 1793. The intensity appeared to fade by the beginning of 1794, in part because Congress passed an amendment to the law allowing distillers to sell whiskey to the army to help pay the excise tax. Another amendment adopted on June 5, 1794, allowed trials of excise cases to take place in state, as opposed to federal, courts–just one week after U.S. District Attorney William Rawle (1759-1836) obtained federal writs requiring more than sixty western distillers to appear in federal court in Philadelphia. When U.S. Marshal David Lenox (1753-1828) and the tax supervisor John Neville traveled from Philadelphia to western Pennsylvania with the writs, their presence reignited resistance. On July 16, a nearly twenty-five-minute gun battle at Neville’s home in Allegheny County resulted in the death of one resister. In reaction to this “murder,” an estimated five hundred resisters came back on July 17 to Neville’s house, defended now by ten soldiers from Fort Pitt, and another gun battle ensued. The resisters burned Neville’s home and captured Lenox, who somehow managed to escape with his life. He returned to Philadelphia, where Hamilton and Washington called for military force to suppress the rebellion.

As Washington prepared his 12,950-man army, drawn primarily from New Jersey and Pennsylvania state militia troops, citizens in Philadelphia and other cities including Hagerstown and Baltimore, Maryland, protested the use of military force against their countrymen. By the time troops reached western Pennsylvania in October 1794, most resisters gave in to the futility of opposing the federal forces. Washington’s army found little opposition and easily rounded up many potential resisters but not the supposed leaders of the rebellion, who had fled farther west. When the army marched back toward Philadelphia on November 19, only twenty suspects were in custody. When the army and the prisoners returned to Philadelphia by Christmas Day, the accused rebels were paraded through the city and down Broad Street as trophies.

Many of these prisoners languished in prison for nearly six months while they awaited federal trial for treason. Eventually, only ten of the accused whiskey rebels were tried for treason at the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, which sat in City Hall (later known as Old City Hall, Fifth and Chestnut Streets). Two of these ten men, John Mitchell and Philip Vigol (or Weigle), were convicted due in large part to William Rawle’s expanded definition of treason that combining to defeat or resist a federal law was the equivalent of levying war against the United States and therefore an act of treason. This set a precedent for treason that was used five years later in the aftermath of Fries’s Rebellion in Bucks County. Mitchell and Vigol were the first two Americans convicted of federal treason in American history. On November 2, 1795, Washington pardoned both Mitchell and Vigol after finding one to be a “simpleton” and the other to be “insane.” While these pardons unofficially ended the saga of the Whiskey Rebellion, the government’s use of military force to repress this “rebellion” and questions concerning the legitimacy of these “treasonous” acts remain controversial and are still debated among historians.

Patrick Grubbs is an advanced Ph.D. student at Lehigh University writing his dissertation entitled “Bringing Order to the State: How Order Triumphed in Pennsylvania.” He has also been employed at Northampton Community College in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, since 2009 and has taught Pennsylvania history there since 2011. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Links

National History Day Resources

- “Proclamation on Violent Opposition to the Excise Tax,” February 24, 1794 (National Archives)

- “By the President of the United States of America: A Proclamation,” printed in Gazette of the United States and Daily Evening Advertiser, August 09, 1794 (Library of Congress)

- Correspondence concerning the Whiskey Rebellion (National Archives)