Alien and Sedition Acts

Essay

A culmination of political battles between Democratic-Republicans and Federalists while Philadelphia served as capital of the United States, the federal Alien and Sedition Acts imposed stringent new rules governing political speech and writings, immigration rights, and non-naturalized immigrants. They also had an immediate impact on the political life of Philadelphia as they inflamed passions in the region, resulted in charges against many newspaper publishers, and contributed to the outbreak of Fries Rebellion.

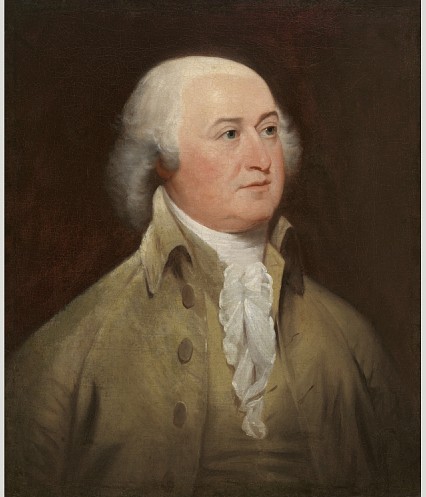

When President John Adams (1735-1826) assumed office in 1797, relations between France and the United States had deteriorated, leading to the Quasi-War of 1798-1800. Though the U.S. in 1793 had taken a position of neutrality in France’s war with Great Britain, the French seized American shipping and rejected Adams’s efforts to negotiate peace. In what became known as the XYZ Affair, the revolutionary French government demanded a large loan, bribe, and official apology from Adams before negotiations could begin. The American mission rejected these terms and news of the XYZ Affair created a political firestorm across the United States, especially in Philadelphia.

In response to concerns about invasion by the revolutionary French government, the Federalist-dominated Fifth U.S. Congress enacted legislation in 1798 to shore up national defense from both foreign and domestic threats, including an increase in military spending for the army and navy. In addition, the Federalists passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, four laws dealing with perceived domestic threats, including criticism by Democratic-Republicans that the Federalists thought undermined national security.

Naturalization Act

The first of the Alien and Sedition Acts was the Naturalization Act, which increased the residency requirement for American citizenship from five to fourteen years. The Federalists intended to stop newly arrived immigrants from voting because they were a major constituency for the Democratic-Republican Party. The second law was the Alien Act, which allowed the president to imprison or deport aliens considered dangerous to the United States at any time. The third was the Alien Enemies Act, which allowed the president to deport any male citizen of a hostile nation during times of war.

The last of these laws, the Sedition Act, was perhaps the most controversial. The Sedition Act outlawed actions or conspiracies against government policies and banned false or malicious publishing against federal officials, including members of Congress and the president. This represented one of the strongest attacks on the First Amendment in American history and created a major political backlash against President Adams and the Federalists in Congress. Notably absent from the protections of false or malicious publishing was the vice presidency, at the time occupied by Vice President Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), the leader of the Democratic-Republican Party.

The Sedition Act, despite attacking the First Amendment rights of newspaper editors and contributors, substantially liberalized the law of seditious libel. Under English common law, the truth of a published allegation was no defense from accusations of sedition, indeed, it could be worse if it was true. Under the new Sedition Act, the truth could be used as a defense against the charge of sedition. Regardless of this liberalization, the Sedition Act was wildly unpopular to Americans.

Sedition Act

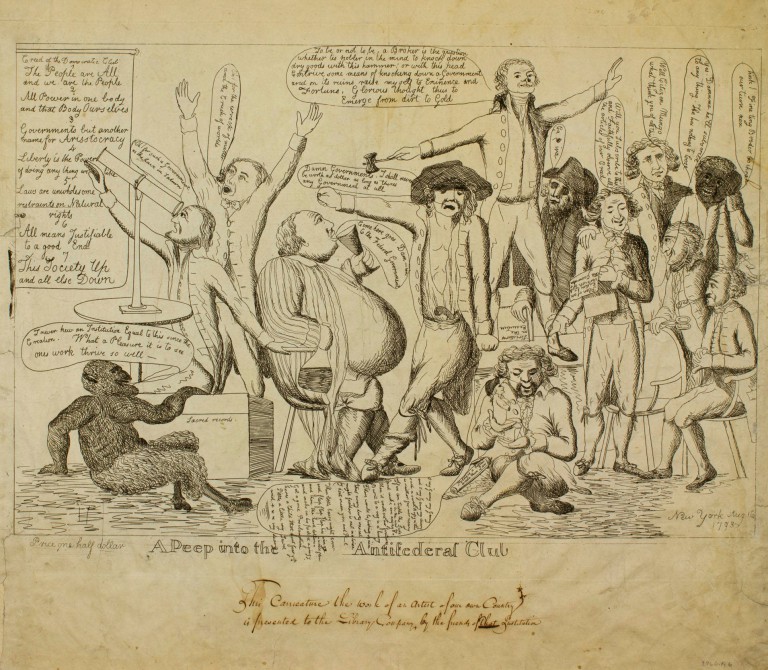

The Sedition Act was particularly important to the Federalists because it allowed them to clamp down on rival political newspapers. Throughout the 1790s, newspapers were by far the most important political battleground particularly in Philadelphia, the nation’s capital. The Democratic-Republican press, spearheaded by editors such as the grandson of Benjamin Franklin (1706-90), Benjamin Franklin Bache (1769-98) at the Philadelphia Aurora, had been gaining on their Federalist rivals. Indeed, by 1800, Democratic-Republican-leaning newspapers far outnumbered Federalist newspapers despite the Sedition Act. Bache was one of seventeen publishers jailed under the provisions of the act; he died of yellow fever in 1798 awaiting trial. Bache’s successor at the Aurora, William Duane (1760-1835), was tried but acquitted. Matthew Lyon (1749-1822), a Democratic-Republican member of the House of Representatives from Vermont was also jailed under the Sedition Act. He was later reelected from jail by his constituents.

The Alien and Sedition Acts helped incite Fries Rebellion in rural Pennsylvania counties northwest of Philadelphia. With passage of the 1798 war program, including new taxes and the Alien and Sedition Acts, German-Americans of the region protested. President Adams declared the area in rebellion and sent troops to arrest the insurgents.

Democratic-Republican leaders James Madison (1751-1836) and Thomas Jefferson opposed the Alien and Sedition Acts by authoring, respectively, the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions passed by the Virginia and Kentucky legislatures in 1798. The Virginia Resolutions called upon other states to declare that the Alien and Sedition Acts violated the First Amendment while the Kentucky Resolutions went further and asked the states to declare “these acts void and of no force.” None of the other state legislatures agreed. Delaware, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey discussed but rejected the resolutions, which are widely seen as precursors to later nullification principles espoused during the antebellum period.

As home to the federal government and a large, partisan press corps, Philadelphia in the 1790s stood at the center of political and legal battles over the Alien and Sedition Acts. The Democratic-Republicans gained support in the city and state as Federalists used severe tactics against publishers Bache and Duane, and sent troops to arrest the protesters of Fries Rebellion. This Federalist overreach in southeastern Pennsylvania and Philadelphia in large part hastened the splintering and decline of the Federalist Party before the election of 1800.

Nathaniel Conley is a doctoral student at the University of Arkansas whose research focuses on the border between Maryland and Pennsylvania with emphasis on the lower class and the border between slavery and freedom. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University