Entomology (Study of Insects)

Essay

Philadelphia and its nearby localities became important sites for entomological study by the nineteenth century due to the presence of the Academy of Natural Sciences (established in 1812) and the American Entomological Society (1859). Entomological writing and illustration also flourished in this center for book production. Over time, entomologists’ interest in insects shifted from the practical and taxonomic to become more focused on ecology and educational outreach.

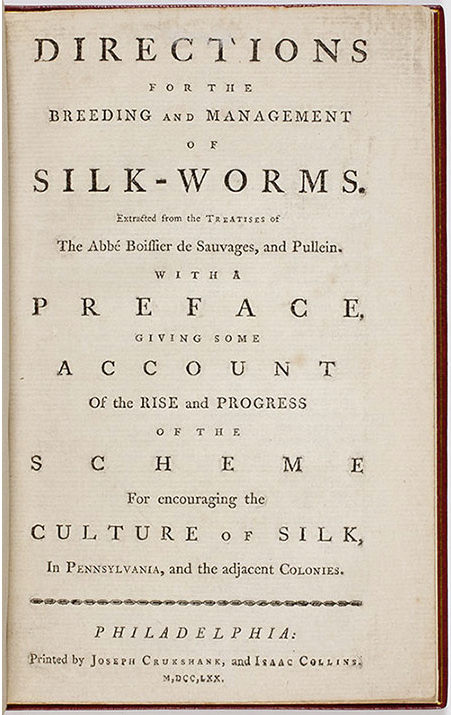

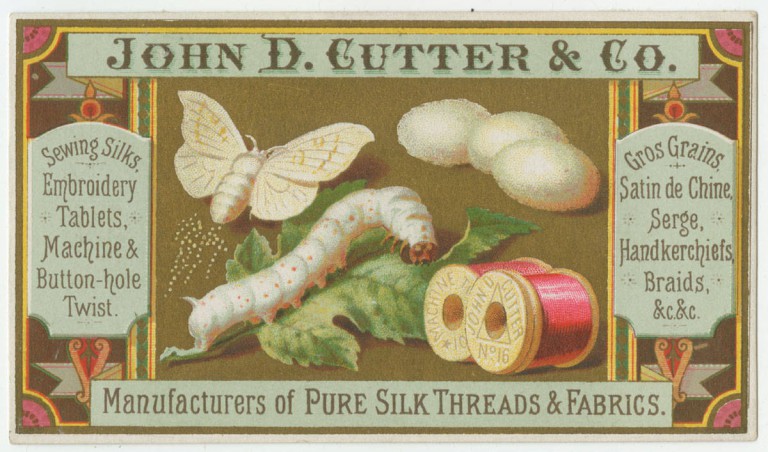

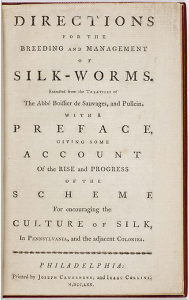

Eighteenth-century Philadelphians often expressed scientific interest in insects in relation to agricultural or economic matters. In 1768, Samuel Pullein (fl. 1734–68?) published The Culture of Silk to encourage American silk production. The treatise explained how to rear silkworms, the larvae of the domesticated silk moth (Bombyx mori). Pullein’s instructions proved to be very popular, and in 1769 Dr. Cadwalader Evans (1716–73) wrote to Benjamin Franklin (1706–90) for advice on introducing silk production to Philadelphia. Franklin suggested the creation of a public filature, an establishment for reeling silk from cocoons. By 1770, Evans and other prominent Philadelphians had organized a silk society. The following year their filature reeled 155 pounds of silk for export. Although the scheme ultimately failed, Philadelphians’ fascination with insects was just beginning.

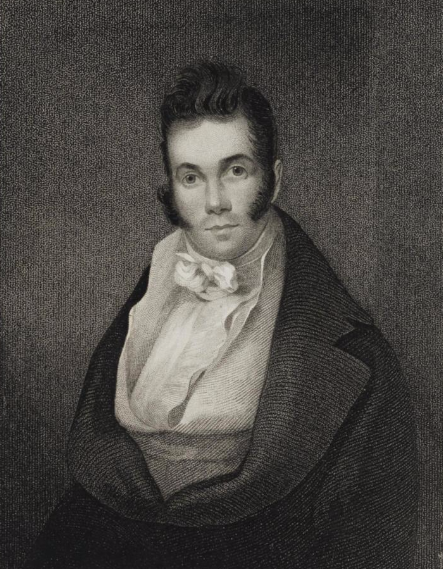

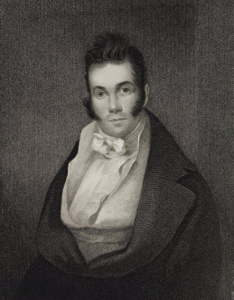

Philadelphia’s early contributions to the study of entomology were largely due to the pioneering work of Thomas Say (1787–1834), a descriptive taxonomist. In 1812, Say joined the Academy of Natural Sciences, which became an important venue for his entomological collaborations, including American Entomology. In the absence of a comprehensive field guide to insects, Say sought to provide descriptions and color illustrations of all known species in North America. Fellow academy members Charles Alexandre Lesueur (1778–1846) and Titian Ramsay Peale (1799–1885) executed many of the drawings. Apart from a preliminary set of plates and descriptions issued in 1817, the three-volume work was printed in Philadelphia between 1824 and 1828. Before his untimely death by typhoid, Say discovered and formally described more than 1,500 insect species.

A New Way of Displaying Insects

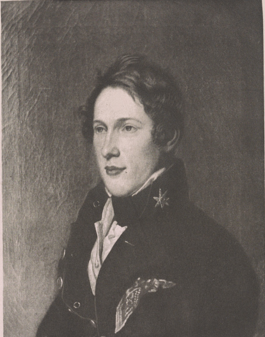

Titian Peale, the youngest son of Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827), was primarily interested in Lepidoptera, the taxonomic order that encompasses butterflies and moths. He curated an impressive collection of roughly four thousand specimens, for which he designed what entomologists call a “book box.” In the 1820s, Peale began hermetically sealing his butterflies in glass boxes lined with tin foil. Entomologists usually preserved insect specimens by pinning them to an opaque surface lined with cork; Peale’s boxes allowed them to study specimens from both above and below by pinning specimens to small cork discs glued to the glass bottom of the box. Peale displayed these boxes at the Philadelphia Museum. In 1899, the Academy of Natural Sciences acquired Peale’s collection. It is one of the oldest collections of insects in the United States.

Concurrently, women produced popular works that diffused entomological knowledge beyond the walls of scientific societies and museums. Philadelphia Quaker and abolitionist Mary Townsend (c. 1814–51) wrote Life in the Insect World in 1844. Townsend emphasized the practical uses or lives of insects, portraying them as diligent workers, careful artisans, and clever tradesmen. In doing so, Townsend argued for cosmic design—even small, seemingly unappealing creatures had purpose and were evidence of God’s goodness. Didactic works that used science to cultivate religious sensibility were considered to be appropriate fare for young women.

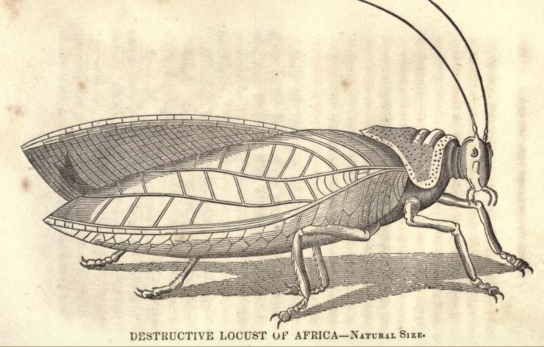

In 1859, Philadelphia became home to what would become the country’s oldest continuously active entomological society, the Entomological Society of Philadelphia. Prominent founding members included John Lawrence LeConte (1812–97), a specialist in Coleoptera (beetles), and Ezra Townsend Cresson Sr. (1838–1926), a specialist in Hymenoptera (bees, wasps, and ants). Lucy Say (1801–86), the wife of Thomas Say, became a member in 1863. The society produced various publications, including its scholarly proceedings. It also distributed, at first gratuitously and later by subscription, a circular called The Practical Entomologist. This serial aimed to acquaint farmers and agriculturalists with useful entomological knowledge. Content ranged from advice on how to deal with problematic species to the basics of taxonomy. In 1867, the society changed its name to the American Entomological Society (AES).

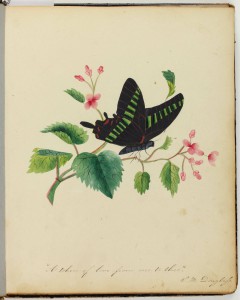

Illustrating Specimens

By the late nineteenth century, Philadelphia was home to a number of women illustrators. Local artist Mary Peart, along with Lavinia Bowen (b. c. 1820) and Patience Leslie, primarily illustrated Butterflies of North America by William Henry Edwards (1822–1909), issued in parts between 1868 and 1897. Rather than drawing from dead specimens, Peart raised and observed butterflies in her Philadelphia residence to more accurately draw and color the larval and pupal stages of her subjects. Ultimately, Edwards believed that Peart contributed more to the work than he did. In raising so many insects, she learned and passed on a great deal of information about the life cycles and habits of moths and butterflies.

Love of entomology passed from one generation to the next. Two of Ezra Townsend Cresson Sr.’s sons followed in his footsteps and became entomologists, working for periods of time at both the Academy of Natural Sciences and the American Entomological Society. George Bringhurst Cresson (1859–1919), like his father, specialized in Hymenoptera, working as a conservator at the Entomological Section of the Academy of Natural Sciences in the 1880s. Ezra Townsend Cresson Jr. (1876–1948) specialized in Diptera, the order that encompasses true flies. Cresson Jr. became a curator in at the Academy of Natural Sciences. He contributed to entomological publications up through the 1940s, co-editing the Academy’s bimonthly serial, Entomological News, with Phillip Powell Calvert (1871–1961). Under their stewardship, the publication became increasingly interested in the study of species’ evolution to expand classical taxonomy of insects.

Meanwhile, rising concern over invasive insect species prompted entomologists to team up with local Philadelphians and the United States government. In 1916, Japanese beetles (Popillia japonica) appeared in Burlington County, New Jersey. Without natural predators, the beetles spread quickly, ravaging crops and ornamental plants. From roughly a dozen insects, their numbers escalated to one thousand quarts of insects captured largely by local children, during the summer of 1920. By 1923, and despite the efforts of entomologists, the infested area spanned seven hundred square miles with no sign of abatement. The situation prompted the U.S. Department of Agriculture to form the Division of Japanese Beetle Control in 1928; in 1933, in an early biocontrol effort, researchers produced the first commercial microbial pesticide, Milky Spore, first detected in New Jersey. By the 1940s, various branch offices littered the state; the Philadelphia office was responsible for quarantining beetles in the eastern third of Pennsylvania. Japanese beetles remained an invasive pest into the twenty-first century.

Interaction with the public was not limited to invasive species. Although the Academy of Natural Sciences and the American Entomological Society continued to foster entomological research well into the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, by the end of this period, the two institutions increased efforts to educate young children. In 1986, the AES established the Calvert Award for young entomologists in honor of former AES president Dr. Phillip Powell Calvert. AES additionally offered an Insect Field Day for school-age children in conjunction with the Academy of Natural Science’s two-day Annual Bug Fest. Visitors to the Academy of Natural Sciences’ museum could enjoy the live butterfly exhibition in addition to its impressive collection of preserved specimens. Other entomological exhibits geared toward children also emerged. In 1992, the Insectarium, a museum of live insects, opened in North Philadelphia.

Though the goals of entomological study were varied, throughout its history, Philadelphians maintained a steady interest in insects. By the twenty-first century, outreach efforts worked to preserve this fascination among future generations.

Jessica Linker is a doctoral candidate at the University of Connecticut, Storrs, and the recipient of fellowships from a number of Philadelphia-area institutions, including the Library Company of Philadelphia, the American Philosophical Society, and the McNeil Center for Early American Studies. Her work focuses on American women and scientific practice between 1720 and 1860. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- 'Bug Crawl' offers a taste of the insect world at the Morris Arboretum (WHYY, July 16, 2013)

- Tonight’s Lecture: Collecting Butterflies in Solitary (WHYY, September 9, 2013)

- How to make bugs appetizing with insect librarian Isa Betancourt (WHYY, January 8, 2014)

- Rare half-male, half-female butterfly discovered at Philly museum (WHYY, January 8, 2015)

- How social societies may play a role in insect brain size (WHYY, July 9, 2015)

- Still life: Art in the service of science (WHYY, December 10, 2015)

- Think Inside the Box (WHYY, December 11, 2015)

Links

- Mary Townsend (Journal of the Sierra College Natural History Museum)

- The American Entomological Society

- Philadelphia's 'Strangling Bug' of 1899 and the American Entomological Society (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Bug Fest (Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University)

- Entomology (Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University)

- Pennsylvania Insects and Other Bugs

- New Jersey Insects and Other Bugs

- Delaware Insects and Other Bugs

- Encyclopedia Smithsonian: State Insects