Herpetology (Study of Amphibians and Reptiles)

Essay

Over the course of three hundred years, urbanization and habitat loss in the Philadelphia region threatened amphibians and reptiles that once fostered rich scientific discussions. Nevertheless, pioneering herpetologists influenced medical, paleontological, and ecological studies of these creatures in North America.

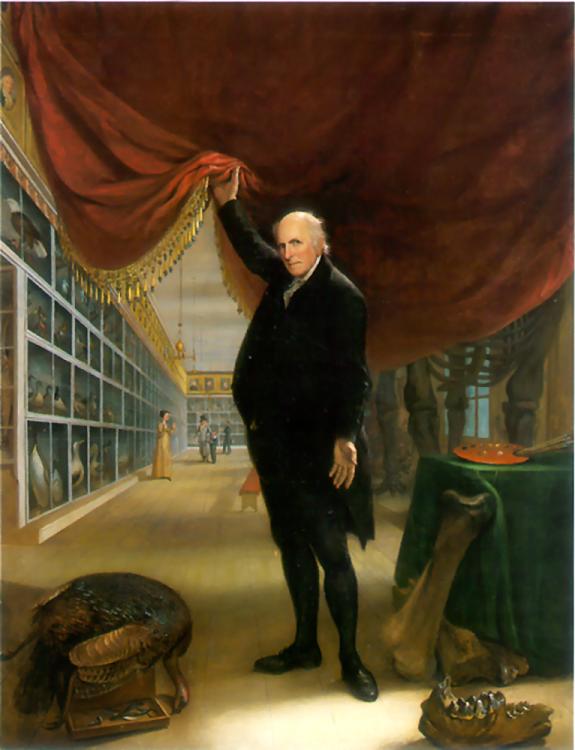

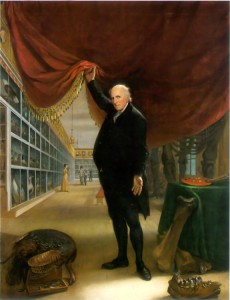

Beginning in the eighteenth century, naturalists on both sides of the Atlantic became entranced with unusual North American herpetological specimens. Rattlesnakes, for example, were prized for their curious rattles, live births, and deadly venom. In February 1746, Philadelphia scrivener Joseph Breintnall (?-1746) wrote to Peter Collinson (1694–1768) about the deleterious effects of rattlesnake venom on his body; Breintnall’s account of his self-treatment of a rattlesnake bite was read before the Royal Society in London. Dangers posed by the snakes did not deter naturalists from seeking them out. In 1797, Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827), proprietor of the Philadelphia Museum, and French naturalist A.M.F.J. Palisot de Beauvois (1752–1820) traveled to Bridgeton, New Jersey, to snare rattlesnakes. They returned with nine live specimens, which they studied and put on display at Peale’s museum.

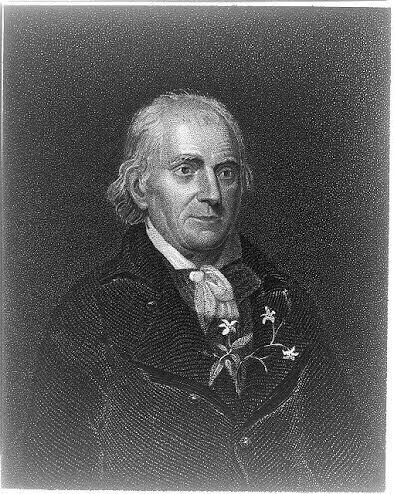

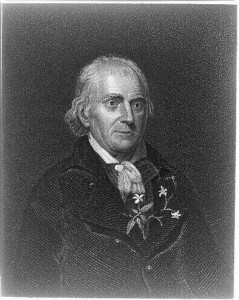

Philadelphia-area naturalists produced a number of important herpetological publications in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Between 1773 and 1777, the famed Kingsessing naturalist William Bartram (1739–1823) traveled through the American South, documenting various species of reptiles and amphibians in the process. Bartram illustrated the head and carapace of a soft-shelled turtle for an account of the trip, popularly known as Bartram’s Travels (1791). In addition to various papers published in the proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences and the American Philosophical Society, two early herpetological synopses printed in Philadelphia were American Herpetology (1827) by Richard Harlan (1796–1843), published in 1827, and North American Herpetology by John Edward Holbrook (1796–1871). Holbrook, from South Carolina, sought to create a comprehensive illustrated index of North American reptiles and amphibians, providing both descriptions and plates of frogs, toads, lizards, salamanders, alligators, and turtles. The work originally appeared in 1836, but was panned for poor coloring. For the better-known, five-volume set appearing in 1842, Holbrook corresponded with naturalists more familiar with living species to fix this problem. One of these was Maria Martin Bachmann (1796–1863), whom he credited as “Miss Martin” on the plate of the Coluber Constrictor.

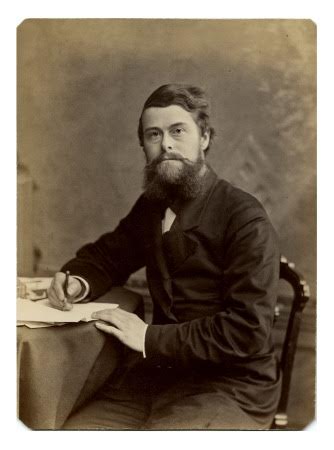

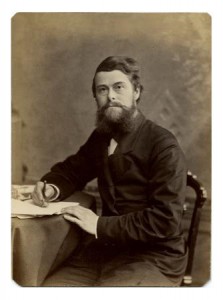

Noted Philadelphia physician Silas Weir Mitchell (1829–1914) performed a number of herpetological experiments beginning in the 1860s. In 1861, he published Experiments and Observations upon the Circulation of the Snapping Turtle, in which Weir described his work monitoring turtles’ blood pressure. His study convinced Weir that the prevailing view of turtle respiration proposed by Robert Townson (1762–1827) in 1795 was incorrect. Weir later co-authored Researches upon the Anatomy and Physiology of Respiration in the Chelonia in 1863, arguing that turtle respiration more closely represents that of higher vertebrates than of amphibians. Herpetology informed Mitchell’s work as a physician; he also studied the effects of rattlesnake venom, which prompted herpetologist Edward Drinker Cope (1840–97) to name the speckled rattlesnake (Crotalus mitchelli) after him. Cope spent most of the early 1860s studying salamanders; amphibians and reptiles remained important to his later paleontological work. In 1869–70, Cope published his Systematic Arrangement of Extinct Batrachia, Reptilia, and Aves of North America.

Although many Philadelphia herpetologists were interested in North American species, a number of nineteenth-century naturalists collected species from Central and South America; examples can be found at the Academy of Natural Sciences. In the twentieth century, Alice Middleton Boring (1883–1955) looked to Asia and expanded American knowledge of Chinese species. Philadelphia-born Boring was initially interested in cell biology. She trained at Bryn Mawr, where she received a bachelor’s degree in 1904 and a doctorate in 1910. In 1918 she left to teach in China at Peking Union Medical College and became engaged with herpetology, authoring and co-authoring several studies of Chinese amphibians and reptiles in the 1930s and 1940s.

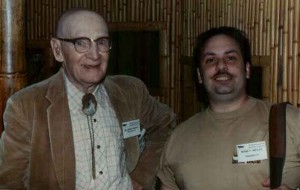

Around the same time, Roger Conant (1909–2003) came to Philadelphia. He became the curator of reptiles at the Philadelphia Zoo in 1935 and director of the entire institution in 1967. In 1952, he founded the Philadelphia Herpetological Society, which, in addition to facilitating outreach and education, operated a nature preserve in southern New Jersey. Conant described new species of water snakes and wrote Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of the Eastern United States in 1958. Through his influence, the Philadelphia Zoo remained an important institution for herpetological study and conservation into the twenty-first century. Other area institutions that maintained educational live animal exhibits emphasizing herpetological conservation in the early twenty-first century included Drexel’s Academy of Natural Sciences and Adventure Aquarium, in Camden, New Jersey. Beginning in 2012, Adventure Aquarium participated in a program for sea turtle rehabilitation, tracking, and conservation based at the North Carolina Aquarium.

Herpetologists’ increased emphasis on conservation by the twentieth and twenty-first centuries was consistent with national trends, but was also attentive to ecological changes in the Greater Philadelphia area. Philadelphia’s growth eliminated or reduced the natural resources various species of snakes, turtles, frogs, and salamanders needed to thrive. Some animals, like turtles, suffered depopulation after being targeted for the food industry. While their predecessors were concerned with possessing and displaying nature, modern herpetologists became attuned to the ways industrialization, pollution, and the introduction of nonnative species altered historic populations and sought to maintain healthy biodiversity in an urban environment.

Jessica Linker is a doctoral candidate at the University of Connecticut, Storrs, and the recipient of fellowships from a number of Philadelphia-area institutions, including the Library Company of Philadelphia, the American Philosophical Society, and the McNeil Center for Early American Studies. Her work focuses on American women and scientific practice between 1720 and 1860. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Academy of Natural Sciences displays 200 years of curiosities — including 'Frankensquid' (WHYY, March 23, 2012)

- 800 lb. alligator star of 'Endangered Species Day' at Adventure Aquarium (WHYY, May 17, 2013)

- Sea turtle rescued last year in New Jersey moving to San Diego aquarium (WHYY, November 10, 2014)

Links

- Philadelphia Herpetological Society (herpetology.com)

- Herpetology (Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University)

- Bartram's Travels (Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina)

- Loggerhead Sea Turtles (Adventure Aquarium)

- Edward Drinker Cope, Third Contribution to the Herpetology of Tropical America (Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia via JSTOR)

- John Edwards Holbrook, North American Herpetology (Biodiversity Heritage Library)