Mummers

Essay

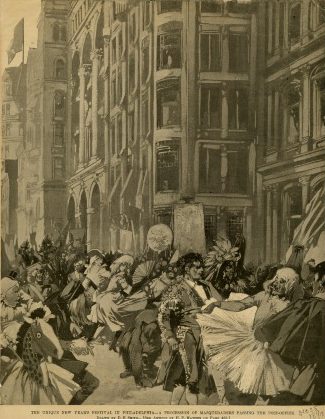

The Mummers Parade, an institution in Philadelphia since 1901, brought together many of the loosely organized groups of folk performers who roamed the streets each year between Christmas Eve and New Year’s Day. Known variously as mummers, shooters, belsnickles, fantasticals, and callithumpians, these masqueraders traced their roots to immigrants from England, Sweden, and Germany who introduced mumming to pre-Revolutionary Philadelphia.

Throughout much of northern Europe and colonial North America, groups of mummers roved from house to house during the Christmas season, entertaining their hosts and expecting food, drink, or a small tip in return. Mumming and belsnickling in southeastern Pennsylvania persisted into the 1800s, not only in Philadelphia but also in smaller cities like Easton, Lancaster, Pottstown, and Reading.

Most nineteenth-century mummers were young, working-class men, and their street-side antics could be raucous. According to the Philadelphia Public Ledger, New Year’s Day 1876 witnessed impromptu parades by men dressed as “Indians and squaws, princes and princesses, clowns… [and] Negroes of the minstrel hall type.” Philadelphia’s new, central police force eventually cracked down on unruly holiday celebrations, and H. Bart McHugh (1879-1935)—a newspaper reporter and theatrical agent—led the effort to bring the mummers to Broad Street for an organized parade, with prizes funded by the city. In 1901 the city of Philadelphia sponsored the first official Mummers Parade, and the Public Ledger reported that “three thousand men and boys in outlandish garb frolicked, cavorted, grimaced, and whooped while the Mayor and members of Councils, Judges, and other officials, State and municipal, looked on.”

Parading Up Broad Street

The original route of the Mummers Parade stretched up Broad Street from South Philadelphia to Cecil B. Moore Avenue (then known as Columbia Avenue) in North Philadelphia. Beginning in the 1920s, the Mummers Parade terminated at Girard Avenue, which shortened the parade route by five blocks. And after 1967, the mummers excised the North Philadelphia portion of the parade altogether, ending their march at the judging stand at City Hall. This contraction of the official parade route dovetailed with the emergence of the unofficial, post-parade celebration in front of the clubhouses on Second Street (or “Two Street”) south of Washington Avenue, where many mummers groups met and rehearsed throughout the year.

From the beginning, most mummers clubs specialized in comedy, music, costume, or dance, leading to an elaborate structure for judging a varied assortment of parade performances. By 2011, mummers clubs competed for over twenty-five awards through the five traditional divisions of the Mummers Parade:

- The comic division (or “comics”), focusing on satire and clowning.

- The wench brigade division (or “wenches”), emphasizing a traditional, burlesque style of female impersonation.

- The string band division (or “string bands”), featuring live music by large ensembles of banjoes and brass.

- The fancy club division (or “fancies”), displaying elaborate costume design.

- The fancy brigade division (or “fancy brigades”), concentrating on Broadway-style staging and choreography.

Until World War II, a plurality of mummers hailed from South Philadelphia, especially from the neighborhood’s Irish American and Italian American enclaves. Kensington and Port Richmond were also well-represented in the early twentieth-century Mummers Parade, and beginning in the 1950s, mummers clubs sprang up throughout the region, especially in Northeast Philadelphia and the New Jersey suburbs.

African American Participants

African American mummers regularly competed for prizes on Broad Street between 1901 and 1929, and African American composer James Bland (1854-1911) wrote the parade’s unofficial theme song, “Oh! Dem Golden Slippers.” However, the mummers in later years developed a reputation for racial insensitivity. Many mummers marched in blackface makeup until the city banned the practice following civil rights protests organized by Cecil B. Moore (1915-79) and the Philadelphia chapter of the NAACP in 1963. In the early decades of the twenty-first century, blackface still appeared at the nighttime party on “Two Street,” after the official parade, and both the burlesque “wench” costume and the mummers’ “strut” (the signature dance step of the parade) originated on the minstrel-show stage. In 2013 the Joseph A. Ferko String Band celebrated the mummers’ connection to minstrelsy with a controversial parade routine titled “Bringin’ Back those Minstrel Days,” performed in brown rather than black makeup to avoid censure by the judges.

Despite its troubled racial history, the Mummers Parade grew considerably more diverse and inclusive after 1963. In the 1970s most mummers clubs began admitting women as performers for the first time. Women had long worked behind the scenes, helping to stitch the mummers’ costumes, and one woman—a newspaper reporter named Laura Lee—snuck into the parade in 1929. In 1984 the Goodtimers Comic Club, with an African American president and hundreds of minority members, started competing in the parade. And in 1992 a group of Cambodian American artists and students teamed up with the Golden Sunrise Fancy Brigade to stage a Khmer dance drama on Broad Street. At the behest of the Philadelphia Human Relations Commission, the 2016 Mummers Parade included a new, noncompeting unit called the Philadelphia Division, organized with the explicit goal of making the parade more diverse. Participants included a Mexican American carnival organization, an African American drill team, a Puerto Rican bomba group, and a brigade of drag queens. Although most mummers clubs embraced the growing diversity of the parade, reports of individual marchers using racist and homophobic slurs along the parade route complicated efforts to make the Mummers Parade more inclusive.

Turning to Corporate Sponsors

By the early twenty-first century, the Mummers Parade drew roughly eight thousand marchers and fifty thousand spectators on a typical New Year’s Day, and hundreds of thousands of viewers watched the parade on local television. Until the financial crisis of 2008-9, the city of Philadelphia offered roughly $350,000 in cash prizes to be divided among all but the lowest-scoring groups in the parade. The withdrawal of city support forced the mummers to turn to corporate sponsors, including Southwest Airlines and SugarHouse Casino, to reimburse the city for the extra police and sanitation services that the parade required. In addition, almost twenty mummers clubs closed or consolidated during and after the 1990s, under pressure from dwindling membership, shrinking audiences, and the rising cost of mounting a parade performance.

Despite these challenges, the mummers maintained a strong record of resilience. Since 1901 the Mummers Parade has been canceled only twice, in 1919 and 1934 (although weather has sometimes forced a delay in the parade until the Saturday after New Year’s). The Mummers Museum opened in 1976 to mark America’s bicentennial, a symbol of the mummers’ contribution to regional and national culture. When the number of spectators for the Mummers Parade started to decline, the city moved the parade route from Broad Street to Market Street to boost attendance—first in 1995, and again from 2000 to 2003. In addition, the fancy brigades began competing indoors at the Pennsylvania Convention Center in 1998, which allowed fans to enjoy their performances without enduring the cold temperatures outside.

Many mummers resisted these changes, but faced with ongoing membership declines and stagnant audiences, the mummers decided to reverse their parade route in 2015 by beginning at the City Hall judging stand and proceeding southward along Broad Street. (The wenches opted out of this route change, insisting on a traditional northward march). This literal change in direction reduced the gaps between performances at popular viewing spots in Center City, boosting the size of the crowds and demonstrating the mummers’ willingness to adapt to the evolving tastes—and shortening attention spans—of the twenty-first century.

Christian DuComb, Ph.D., is assistant professor of theater at Colgate University and the author of Haunted City: Three Centuries of Racial Impersonation in Philadelphia (University of Michigan Press, 2017). He performed as a comic in the Mummers Parade from 2009 to 2012. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Economy clips Mummers' feathers (WHYY, December 30, 2011)

- Cross-dressing at the Mummers Parade (WHYY, December 31, 2012)

- Mummers strut for 125th time (WHYY, January 1, 2013)

- Mummers Fancy Brigades apply last-minute glitz, paint and elbow grease (WHYY, December 31, 2013)

- Mummers' unofficial anthem composed by local black musician (WHYY, January 1, 2014)

- Mummers Parade performs an about-face (WHYY, December 29, 2014)

- Golden Sunrise, the last fancy club, prepares to Mummer it up for 2015 (WHYY, December 31, 2014)

- Lamenting Mummers' rerouting, applauding South Philly spirit (WHYY, January 2, 2015)

- Annual stop at Ladder 5 shows Mummers’ respect for 9/11 responders (WHYY, December 23, 2015)

- Mummers hope getting more diverse will help boost crowds and ranks (WHYY, December 30, 2015)

- Protestors try to interrupt Mummers Parade (WHYY, January 1, 2016)

- Kenney addresses Mummers incidents (WHYY, January 4, 2016)

- A kinder, gentler Mummers Parade appears to be in Philly's future (WHYY, January 6, 2016)

- Casino signs four-year deal to sponsor Mummers Parade (WHYY, December 16, 2016)

- After sensitivity training, will Mummers rein in raucous antics? (WHYY, December 22, 2016)

- Milder Mummers strut into 2017 (WHYY, December 30, 2017)

- City to Mummers judges: Please be nicer (Billy Penn via WHYY, December 31, 2019)

- Mummers leader says he wants to work with Mayor Kenney to keep parade (WHYY, January 24, 2020)