National Parks

Essay

National parks figure prominently in Greater Philadelphia’s cultural, economic, and natural landscapes. Morristown (1933), Independence (1948), Valley Forge (1976), and First State (2015) National Historical Parks all preserve and provide access to sites associated with the American Revolution and early American history. Together they welcome nearly six million visitors each year and create more than four thousand jobs in surrounding communities, thereby generating considerable economic activity throughout the region. Alongside other regional units of or supervised by the National Park Service, including historical sites, memorials, heritage areas, historic landmarks, historic properties, an agency headquarters, and a sprawling nature reserve, the national parks reflect a longstanding and ongoing investment by the federal government in protecting the region’s rich natural and cultural resources.

Established in 1916 amid a Progressive impulse to preserve the nation’s scenic treasures, the National Park Service began its work primarily in western states, far removed from the East’s burgeoning population centers. Agency leaders worked to shift the balance by establishing parks throughout the eastern states and expanding their scope to include sites of historical significance. Doing so, however, put the National Park Service into competition with state and local preservation organizations, which had spread throughout the country following the Civil War. Also at odds with this mission was the War Department, which since the 1890s had been charged with supervising national military parks.

Despite the increasingly competitive heritage landscape, National Park Service leaders scoured the region looking for footholds to expand the agency’s stewardship across all federal parks. Their search led to Morristown, New Jersey, in 1932. Although no battles ever occurred there, Morristown was storied for its association with George Washington (1732-99) and two encampments of the Continental Army, particularly during the hard winter of 1779-80. Because Morristown was not a battlefield, it was not subject to the War Department’s supervision. Although a private organization formed to protect Morristown’s historic structures during the 1870s, it struggled financially during the 1920s and 1930s despite growing public interest in the site. Against the backdrop of George Washington’s two-hundredth-birthday celebrations in 1932, National Park Service leaders together with local enthusiasts convinced Congress to establish the nation’s first national historical park at Morristown. President Herbert Hoover signed the act into law in 1933.

Morristown was not the agency’s first historical unit—it had established two historical monuments in Virginia in 1930—but was the first to be designated a historical park, which implied a scale and significance akin to iconic wilderness parks like Yosemite and Grand Canyon. It was a crucial step in prompting a massive reorganization in 1933 that placed all of the nation’s federal parks, monuments, and historic sites under National Park Service supervision. In the Historic Sites Act of 1935, Congress authorized the agency, for the first time, to seek out and preserve historic sites and properties of particular significance. In this regard, Morristown was a catalyst for creating an expansive history program within the agency that, in coming years, employed corps of researchers, architects, and preservationists.

A Nudge from the New Deal

The impact of the reorganization was immediately evident throughout Greater Philadelphia, in part because of additional initiatives of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. With the country deep in economic crisis, the Roosevelt administration sought to ease anxieties and provide job relief by commissioning a network of recreational areas on past-prime lands bordering the nation’s urban areas. These included nearly six thousand acres reclaimed in 1935 from a centuries-old iron plantation on the border of Chester and Berks Counties forty miles northwest of Philadelphia. Hundreds of men employed by Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps set to restoring old buildings and landscapes so that by 1936, when administration of federal recreation areas passed to the National Park Service, agency leaders inherited a ready-made historic site. Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site entered the system in 1938, only the second historical site designated as such under the Historic Sites Act.

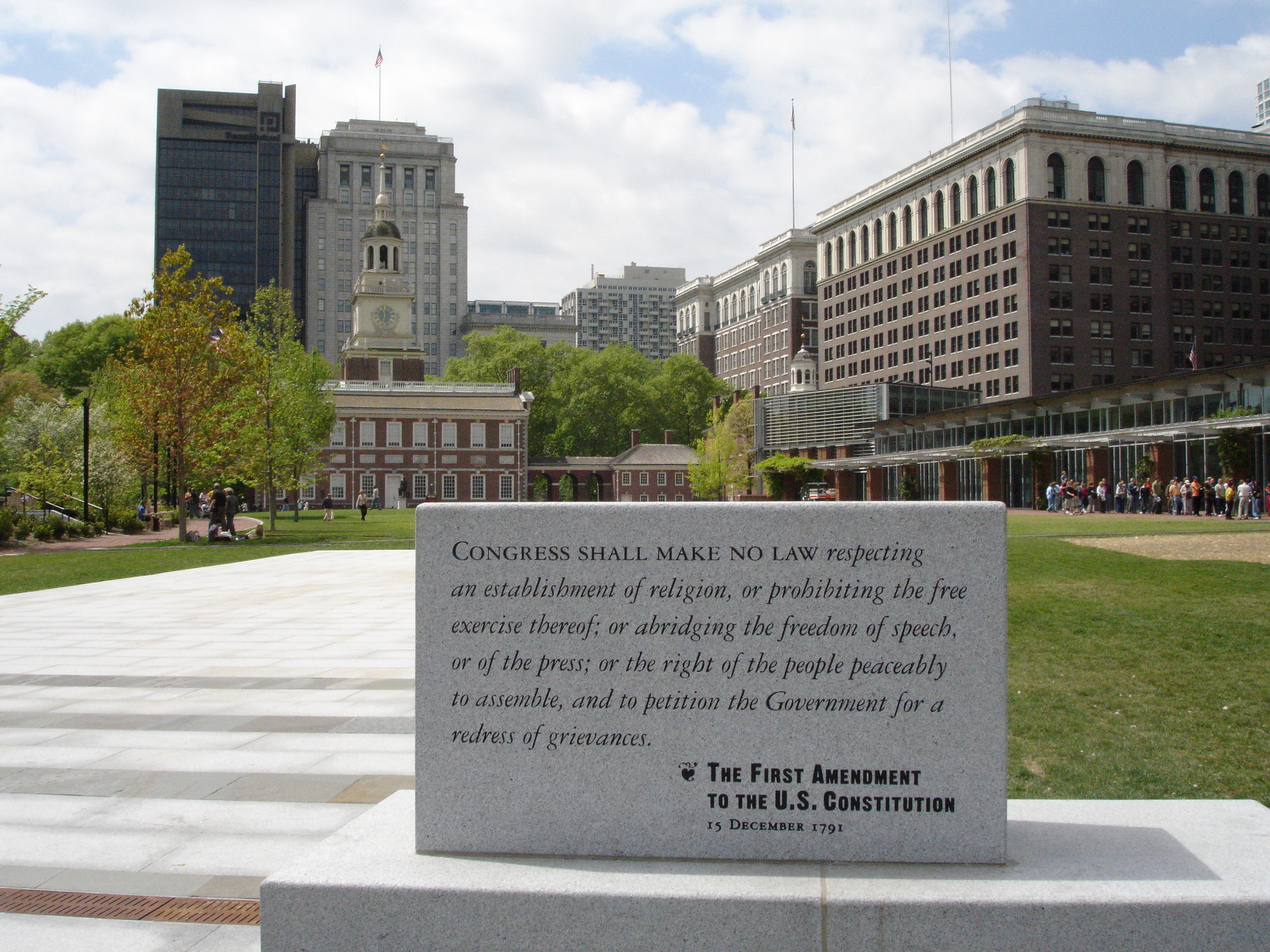

In Philadelphia, meanwhile, citizens motivated by patriotism and concern for the deteriorating urban environment around Independence Hall clamored to leverage the Historic Sites Act to create a national monument encompassing the hall and other buildings associated with the nation’s founding. Making the case for a large park was difficult, however, given a complex web of competing private property interests. The National Park Service made inroads during 1939 when it acquired the old Second Bank of the United States building, just vacated by the U.S. Customs Service and designated it the Old Philadelphia Custom House National Historic Site. In 1942, in South Philadelphia, the National Park Service brokered a cooperative partnership with the stewards of Old Swedes’ Church to establish Gloria Dei Church National Historic Site. In the meantime, a coalition of power brokers including politicians, lawyers, architects, and members of hereditary societies leveraged wartime patriotism toward generating support for a stronger federal presence. It came in 1943 when, with a special presidential waiver of a wartime prohibition against new parks, the National Park Service established Independence Hall National Historic Site. In 1948, having spent the remaining war years haggling over plans with park boosters and city officials, agency leaders and local supporters convinced Congress to authorize Independence National Historical Park.

Though born of World War II, Independence very much embodied the Cold War era. It was, after all, a park committed squarely to promoting the success of American democracy. Its singular focus on the Revolutionary era conveniently excused it from contending with constitutional failures such as those that prompted civil rights activism in the postwar years. What’s more, the National Park Service’s development plan literally created the park’s historical landscape. Throughout the 1950s, bulldozers cleared nineteenth- and twentieth-century buildings to create a mall (initially a state park) north of Independence Hall and a landscaped park extending three blocks to the east. Although some within the agency warned against this approach of displacing people and businesses that did not harmonize with Independence’s historical aesthetic, it reflected the considerable influence of postwar-era urban renewal strategies, which favored “slum” clearance and the expansion of public space in city centers. In this regard, the National Park Service’s energies in Philadelphia advanced a radical transformation of the city’s landscape that was more broadly coordinated by the City Planning Commission and its executive director, Edmund Bacon (1910-2005). The opening of a restored Independence Hall to the public in 1972 thus reflected Philadelphia’s new cachet as a center of historic preservation, but it also bespoke a new vision for urban life at the end of the twentieth century.

The popularity of that vision during the 1970s owed, in part, to the remarkable breadth of activities associated with the nation’s Bicentennial celebration in 1976. Bicentennial fervor made Independence a locus of veneration and protest. But, even beyond Independence, the Bicentennial intensified National Park Service commitments throughout Greater Philadelphia. A campaign emerged to put Valley Forge State Park—set aside in 1893 as Pennsylvania’s first state park—under federal supervision. Washington’s Continental Army suffered a difficult though transformative encampment at Valley Forge during the winter of 1777-78. Public memory of its travails inspired significant commemoration over the years, but a shifting economy and runaway suburban growth exceeded the park’s capacity to protect its resources. After considerable debate throughout the early 1970s, Congress agreed in 1976 to make Valley Forge the region’s third national historical park.

Many Less-Visible Parks

Large historical parks ranked among only the most visible of National Park Service initiatives throughout the region at the end of the twentieth century. Bicentennial energies brought Philadelphia’s Thaddeus Kosciuszko National Memorial (the agency’s smallest unit at .02 acres) into the system in 1972 as well as the Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site in 1978. The agency’s capacity to serve the region owed also to the presence of a thriving field office, established in Philadelphia in 1956. Although the purview and the name of the Northeast Regional Office has shifted over the years, its purpose has been to provide a corps of planners and technicians to nearly eighty parks and other units spread across thirteen states. Its work is not limited to historical units. Regional officers figured prominently, for instance, in brokering the establishment in 1978 of the New Jersey Pinelands National Reserve across nearly a million acres of ancient forest in southern New Jersey.

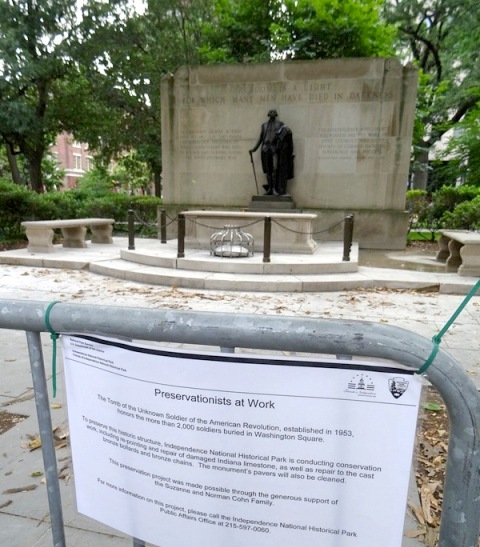

The Pinelands project heralded a new direction for the National Park Service favoring cooperative management—with state, local, and private interests—of mixed-use natural and heritage areas rather than exclusive federal control typical of national parks. This strategy shaped much of the agency’s work throughout the greater Philadelphia area during the early years of the twenty-first century. Beyond sustaining its legacy units, the agency took an advisory role in managing the Delaware and Lehigh National Heritage Corridor (1988), the Schuylkill River Valley National Heritage Area (2000), the Lower Delaware National Wild and Scenic River (2000), the Crossroads of the American Revolution National Heritage Area (2006), and the Washington-Rochambeau National Historic Trail (2009). In addition, through its supervision of the National Register of Historic Places, the agency provided assistance to hundreds of historic properties and landmarks scattered throughout the region.

The Greater Philadelphia area’s distinctive concentration of natural and cultural resources created significant responsibilities for the National Park Service. Despite dwindling budget appropriations in the twenty-first century, Congress continued to create new units to be managed. In 2015 these included the First State National Historical Park, Delaware’s first national park, which was designated to preserve and provide access to sites associated with colonial Dutch, English, Finnish, and Swedish settlements (reaching also into southeastern Pennsylvania). National politics and regional needs thus mixed again with shifting landscapes and the tides of memory to ensure an ongoing and dynamic role for the National Park Service throughout Greater Philadelphia.

Seth C. Bruggeman is an Associate Professor of History at Temple University. His publications include an edited volume, Born in the USA: Birth and Commemoration in American Public Memory (University of Massachusetts Press, 2012), and Here, George Washington Was Born: Memory, Material Culture, and the Public History of a National Monument (University of Georgia Press, 2008). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Delaware's long road to a National Park (WHYY, December 18, 2014)

- Old Swedes Church joins First State National Park (WHYY, May 11, 2015)

- National parks tout economic impact of $30 billion (WHYY, February 28, 2013)

- Shutdown cost national parks at least $414M (WHYY, March 4, 2014)

- Beyond the Uniform: Stories from the National Park Service (WHYY, June 3, 2016)

Links

- Cradle of Independence (PhillyHistory.org)

- Independence National Historical Park

- Valley Forge National Historical Park

- Morristown National Historical Park

- Benjamin Franklin Museum Opens This Weekend, Free of its Old Quirks (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Striking a Chord for Liberty (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- National Park Service

- Hopewell Furnace National Historical Park

- Hopewell Village Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.org)