Pennsylvania Charter of Privileges

Essay

The Charter of Privileges, effective October 28, 1701, and sometimes known as the Charter of Liberties, functioned as Pennsylvania’s constitution until the American Revolution. It replaced several attempts since the colony’s 1681 establishment to create a viable frame of government. Among the more permissive of colonial constitutions in British North America, the document guaranteed religious freedom, strengthened the separation of church and state, granted popularly-elected officials the ability to enact laws, and balanced power between the offices of the governor, legislature, and judiciary. The text of the Charter became regarded as a shining example of the ideals of freedom of worship, human equality, individual rights, and self-government put into practice espoused by Pennsylvania founder William Penn (1644–1718).

In August 1701, during his second visit to Pennsylvania (1699–1701), Penn learned that factions in the British government had introduced legislation to strip him of his colony and place it directly under the monarchy’s control. Fearing the worst, he prepared to depart for England. Before sailing in early November, and with the approbation of the Provincial Assembly, Penn enacted several official measures already under discussion, the most significant of these being a new constitution. Others included a revised Charter for the City of Philadelphia, broadening the power of municipal government; a proposed Charter of Property outlining the rights of landowners (never instituted); and legislation regulating the judiciary. Penn worked on these during his last days in Pennsylvania at his country estate, Pennsbury Manor in Bucks County, and later from his Philadelphia home, the Slate Roof House (at Second Street, just north of Walnut, later the site of Welcome Park). He presented them to the Provincial Assembly where it met, likely at the Friends Public School on Fourth Street, south of Chestnut.

Penn’s theoretical influences in writing the Charter of Privileges and the contemporary notion of individual freedoms can be traced to his Enlightenment era background, Quaker religious principles, and events following England’s 1688 Glorious Revolution. Enlightenment (or Age of Reason, roughly 1650–1780) thinking espoused in part that all humans were equal at birth (a tabula rasa or clean slate), were free to think and reason individually, and were not intrinsically subject to inherited and arbitrary monarchial and class authority. Penn no doubt was familiar with the work of key Enlightenment philosopher John Locke (1632-74), including An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689). Early in life, Penn also heard the teachings of Thomas Loe, a traveling preacher and member of the Religious Society of the Friends of Jesus (or Quakers), who advocated rejection of institutional religion and a more personal relationship with God. Penn converted to Quakerism in the 1660s and through his writings on religion and philosophy rose to become a seminal spokesperson for the Friends. Penn also witnessed the removal of the Catholic King James II (1633-1701) in 1688, and the enactment by Parliament in December 1689 of the English Bill of Rights, which included limiting the power of the monarchy, granting more authority to members of Parliament, and an affirmation of the Enlightenment principle that all people enjoy the same basic rights. These events and ideas were no doubt fresh in his mind as he penned a new constitution for Pennsylvania.

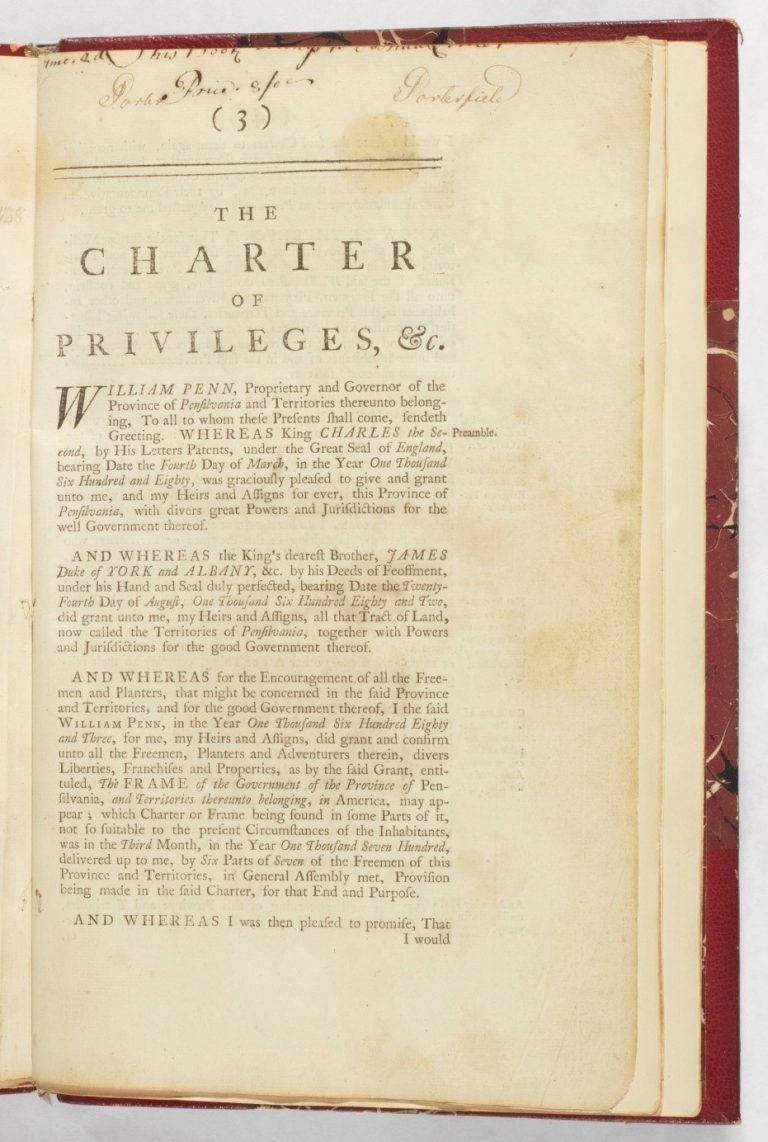

The Charter of Privileges

Members of the Pennsylvania Assembly called the new constitution a Charter of Privileges, for it permitted them certain privileges, liberties, or powers, never before surrendered by Penn. Chief among these was the power to enact legislation, an ability many colonial legislatures lacked: legislation could only originate with the governor and Provincial Council, not popularly elected representatives. Many thought the concept radical, fearing it would engender mob rule. Penn’s earlier frames of government did not grant it, including his First Frame of Government (December 1682), and the Second Frame (April 2, 1683–April 1693). In 1696, with Penn absent from Pennsylvania, the Assembly had attempted its own frame granting this power through acting Governor William Markham (1635–1704). Though in effect from November 7, 1696, to October 27, 1701, Markham’s Frame never gained Penn’s authorization for he feared the idea too liberal. However, with the possibility of a takeover of his proprietary colony by the Crown, Penn permitted the Assembly this ability out of concern for “a violent or arbitrary governor imposed on us” by the royal government, reasoning his colony could defend itself with this new power. The legislature could also choose its own leaders and officers, rather than have the choice made for them by the governor. The legislature accepted the Charter on October 28, 1701.

The Charter of Privileges begins by reiterating a significant clause from earlier frames and the heart of Penn’s “Holy Experiment”—namely, guarantees of freedom of worship, stating that no one “shall be in any case molested or prejudiced … because of his or theire Conscientious perswasion or practice.” Additionally, any male Christian could hold civil office, eliminating the requirement of land ownership. The use of taxes to support religious institutions was banned, further separating church and state. Another provision elevated much of the Assembly’s power to that of the governor and judiciary, creating a tripartite government. The governor’s role was reduced to management status, but still retained veto power. The Charter also created a unicameral legislature, relegating the Provincial Council as an advisory body to the governor. The only American colonial legislature to do so, Pennsylvania remained unicameral with its 1776 Constitution, until the state Constitution of 1790 created a bicameral assembly. Lastly, the Charter authorized the three “Lower Counties on the Delaware” of Kent, Sussex, and New Castle the option to establish their own assembly if they chose. These counties, already established with their own governments long before Penn arrived, were formally granted to him by James, the Duke of York, on August 25, 1681. They separated in 1704, creating the colony of Delaware.

The Charter of Privileges gained respect and admiration in the ensuing decades as a great advancement for representative government. The Liberty Bell, that iconic symbol of American freedom, ordered to be cast by the provincial government in 1751, likely commemorated the fiftieth anniversary of this document. The United States Constitution, the Bill of Rights, state constitutions, and those of countries around the world adopted principles set forth in this Charter as basic tenets of democratic government: religious freedom, separation of church and state, tripartite government, and laws created and enacted by popularly-elected officials.

Linda A. Ries is a retired archivist from the Pennsylvania State Archives, part of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, where she worked for thirty-five years. She is editor of Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, the scholarly journal of the Pennsylvania Historical Association.

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Treasures of the APS: Pennsylvania Charter of Privileges (American Philosophical Society)

- Charter of Privileges (Full Text, Avalon Project, Yale University)

- Teaching Unit: William Penn's Charter of Privileges (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- 1681-1776: The Quaker Province (Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission)

- Discussion of State Constitutions During the Revolutionary Period (UShistory.org)

- Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776 (The Avalon Project, Yale Law School)