Philadelphia Lawyer

Essay

The term Philadelphia lawyer originated in the eighteenth century as a description of members of the Philadelphia bar, then widely considered the best trained in the American colonies and exceptionally skilled in the law and rhetoric. By the twentieth century the term had taken on a less flattering secondary meaning, to denote a clever attorney skilled in manipulating the law for his clients’ advantage. Both definitions continue to be used.

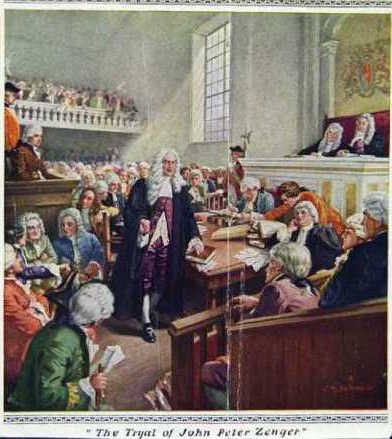

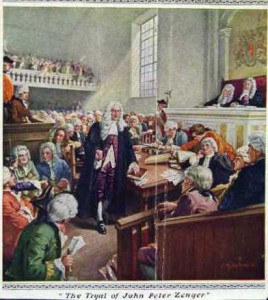

For some time the term was associated with Andrew Hamilton (1676-1741), a Philadelphian who went to New York in 1735 to represent John Peter Zenger, a printer and newspaper publisher who was charged with libel for publishing attacks on the royal governor. At a time when the English common law held that “the greater the truth, the greater the libel,” Hamilton argued that Zenger’s articles were true and therefore could not, by definition, be libelous. Under the common law, jurors were expected, on pain of being arrested and fined themselves, only to determine the facts and were prohibited from determining the law. Much to the chagrin of the judge, the jury found the publisher not guilty in one of the earliest recorded cases of jury nullification, or defiance of legal instruction. Hamilton’s arguments were published in Philadelphia, New York, and London throughout much of the 1700s and were widely admired by other lawyers.

Recent scholarship has questioned Hamilton’s association with the term. Whether it originated with him or not, the term Philadelphia lawyer came to be applied to the city’s legal professionals in general. The province’s early lawyers trained in long apprenticeships under experienced attorneys and political leaders or they went to London to train in the Inns of Court, prototypical law schools, where they received the best English legal training of the time. The phrase “this would puzzle a Philadelphia lawyer” was a common saying by the early nineteenth century, used to describe a problem so difficult it needed a highly skilled specialist to solve. It seems to have entered the language as an English, rather than an American, proverb. The phrase first appeared in print in 1788 in the Universal Asylum and Columbian Magazine published in Philadelphia. An American visiting London wrote to a friend in Pennsylvania, “They have a proverb here which I do not know how to account for;–speaking of a difficult point, they say, ‘it would puzzle a Philadelphia lawyer.’”

Fame for Philadelphia Lawyers

By the middle of the nineteenth century, the term was in common usage in the United States, turning up in novels, biographies, and newspaper and magazine articles, while still being employed by British authors. The German-born writer Francis Joseph Grund (1805-63), in his 1837 book The Americans in Their Moral, Social, and Political Relations, noted that American lawyers had to be better trained than their English counterparts because they had not only to learn the laws of the nation as a whole but also the laws of each state. “The most fertile in argument and scientific distinctions are, I suppose, those of Philadelphia, their fame being established by the adage, ‘This will puzzle a Philadelphia lawyer;’ which is expressive of the same difficulty as the squaring of a circle in mathematics,” he wrote.

As before the Revolution and the founding of the new nation, Philadelphia lawyers remained part of the city’s upper class, set apart from ordinary citizens. Their chief legal business of the early nineteenth century involved the collection of debts and taxes, execution of foreclosures, and recovery of property for landlords and creditors, none of which endeared them to the common people. Often residents met lawyers for the first time when they were evicted or sent to debtors’ prison. It is in this context, Robert R. Bell argues, that “the common opinion was that the law was nothing more than tricks and technicalities, run by unscrupulous men who build legal careers on the disasters of others.”

Nevertheless, references to “Philadelphia lawyer” in print, if not in casual conversation, continued to be largely complimentary throughout the nineteenth century. In modern usage, the term continues to reflect both meanings—a highly skilled, intelligent attorney and a shrewd, unscrupulous lawyer willing to manipulate the law. The phrase became such a part of the American lexicon that the great folksinger Woody Guthrie wrote a song in 1937, “Philadelphia Lawyer,” about a lawyer visting Reno, Nevada, who promised his lover a quickie divorce so “we can get married tonight,” only to be done in by the lady’s husband.

Jodine Mayberry is a retired journalist. She was a legal writer and editor for West Publications, a division of Thomson Reuters, for 18 years.

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Crown v. John Peter Zenger (Historical Society of the New York Courts)

- The Trial of John Peter Zenger (USHistory.org)

- The Universal Asylum and Columbian Magazine (Archive.org)

- Letter from Woodie Guthrie with origins of song "Philadelphia Lawyer," ca. 1940 (Library of Congress)

- "Philadelphia Lawyer" by Woody Guthrie (YouTube)