Public Baths and Bathing

Essay

Public bathing became a civil and social imperative in the Philadelphia region and elsewhere in the United States during the second half of the nineteenth century. Following the cholera epidemic of 1849, which devastated the American population, leaving hundreds of thousands of deaths in its wake, including that of President James K. Polk, it became apparent that cleanliness and personal hygiene were essential to maintain a well-ordered and healthful civilization. During the second half of the nineteenth century people and their governments became aware of the benefits of washing, and the public bathhouse movement was the largest civic effort to meet the growing concerns of squalor in the city.

The practice of bathing in fresh water and in mineral springs began in Europe during the 1760s and 1770s as a product of Enlightenment thinking. Since the middle ages, human bodies in European society were always covered, even while bathing; direct contact to water was generally thought to have been harmful as water could seep into the skin through pores and potentially drown a person from within. The scientific discoveries of the Enlightenment revealed the healthful benefits of exposing bare skin to air and water, thereby setting a precedent for cleanliness and the practice of bathing, which was retained by European colonists who came to America.

However, bathing institutions and facilities were not common in the United States until after the Civil War. The first bathing facilities in the Philadelphia and New Jersey region were located along the Jersey Shore. Long Branch, Asbury Park, and Cape May became wildly popular destinations for public bathing during the 1860s. Prized for their luxurious hotels and resorts, these small ocean towns became centers of recreation for affluent patrons to breathe the salt air and bathe in the refreshing Atlantic tides, escaping the bustle and grime of urban centers like Philadelphia or New York City. The pleasures of resort towns were, however, available only those who could afford to pay the price of luxury. Those who lacked the money and leisure time to travel to the shore bathed illegally in local rivers, docks and wharves. Until the second half of the nineteenth century, urban poor lacked the facilities and services to keep themselves clean.

Growth of Slums

Urban slums grew exponentially through the mid- to late nineteenth century, as immigrants flooded northeastern urban centers that lacked facilities and services to accommodate their growing populations. Many newly arrived Eastern and Central European immigrants lived near the Delaware River in the densely populated areas of Southwark and Northern Liberties. These slums were as crude as livestock pens: the stench of human waste wafted from shared outdoor privies; children splashed in surface drains, and in divots along muddy, unpaved street-gutters resembling potholes, flooded with fetid and stagnant water; white linen hung on clotheslines strung across alleys of crowded two-story row houses, midst the choking smog of nearby factories. To live here, or in any other urban slum in the nineteenth century, meant an intimate relationship with filth. In contrast to the more affluent, who began installing indoor plumbing in their homes as early as the 1840s, Philadelphia’s poor and working class population lacked the means for thorough and frequent washing, which remained a middle and upper class activity.

The devastation of the cholera epidemic of 1849 sparked the public bathhouse movement in cities like New York, which immediately began constructing wash facilities for their poor population. As early at 1860, Philadelphia philanthropists and reformers advocated for the construction of public wash facilities, which they argued would bolster Victorian values of cleanliness and morality, and would become “ladders” of social mobility following nineteenth-century ideology that dirt was the cause of poverty. Baths, they argued, had the power to transform “urban barbarism” into “civic civilization.” However, bathhouses were not constructed in Philadelphia until after the economic crisis of 1893, which added to the growth of urban slums.

Floating baths were the first urban facilities in the United States established to maintain public hygiene. These early bathhouses actually floated in rivers and generally used natural water until many rivers became polluted due to the growth of industry. Philadelphia’s first floating baths were built in the late 1860s in the Schuylkill River, just south of the Fairmount Waterworks. Over time, though, “the discharge of foul matter” from nearby industrial sites and city sewers rendered the river water “unfit for domestic use,” according to the 1873 report of the Board of Health of the City and Port of Philadelphia. As floating baths closed, outdoor public swimming pools were constructed; Philadelphia had eight public swimming pools in 1899 located in immigrant-dense neighborhoods and added fifteen more pools by 1912. While floating baths and swimming pools were great improvements for the hygienic standards of slum life, they both had limitations. First, floating baths and outdoor swimming pools were only open during the spring and summer months. Furthermore, neither were used by the public for hygienic purposes, primarily; but as a way to cool off in the summer months.

Publicly Funded Bathhouses

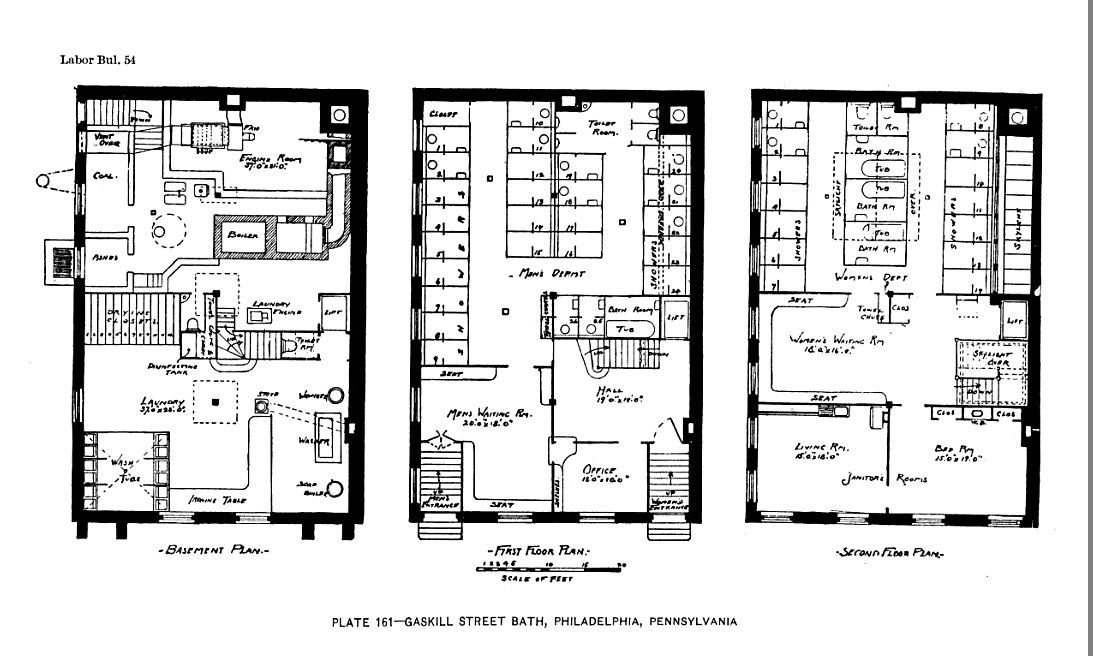

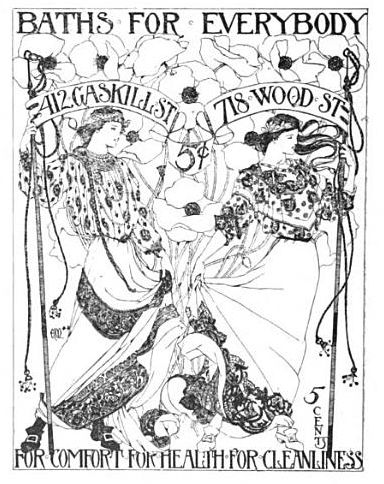

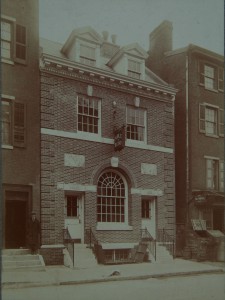

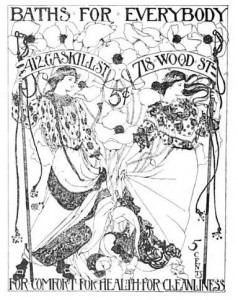

In some cities, including New York, year-round municipal bathhouses were built with municipal funds. This was also the case in Camden, which in the first decade of the twentieth century established a city-funded Public Bath House on Mount Vernon Street north of Fourth Street, with a superintendent who was a member of the Police Department. In Philadelphia the movement was supported by philanthropy. The Public Baths Association (PBA) of Philadelphia was incorporated on March 18, 1895, by a group of progressive reformers and wealthy industrialists. For its first project, the PBA commissioned architect Louis E. Marie of Furness, Evans & Co. to design the Gaskill Street Baths, based on the People’s Baths in New York City. Construction began on Gaskill Street in September 1897, and the bathhouse opened to the public on April 21, 1898; it cost a total of $29,903 for the land and construction labor. Located at 410-12 Gaskill Street, the bathhouse served the city’s poorest population with forty showers and four baths for men and women to use separately. Patrons paid five cents for a shower, and ten cents for a tub bath with a towel and soap.

As the Gaskill Street Baths became popular, averaging eighty-eight patrons per day in 1898, the PBA commissioned other bathhouses throughout Philadelphia. The Wood Street Bathhouse, at 718-20 Wood Street, opened March 30, 1903, followed by the Germantown Road Public Baths at 1203-05 Germantown Avenue on November 12, 1912. The PBA opened two more public bathhouses through the 1920s: Wharton Street Public Baths at Passyunk Avenue and Wharton Street in 1921 and Hazzard Street Public Baths at 1808-14 East Hazzard Street in 1928. By the early twentieth century, public bathing became a socially acceptable practice, which improved the standard of living among the city’s poorest people.

Soon, however, bathhouses declined as fewer patrons used the facilities. In 1908, the Philadelphia Housing Commission was formed as a result of undaunted efforts of the Octavia Hill Association, a housing reform organization formed in 1896. Committed to promoting a clean, safe, efficient, and healthy urban environment, the Philadelphia Housing Commission aided in the enactment of laws that prevented the erection of “unfit” dwellings—including those with inadequate pluming and wash facilities. As indoor plumbing became more prevalent in Philadelphia’s slums, it soon became easier for people to wash at home rather than in public baths. Many bathhouses could not sustain the cost of remaining open with the drop in clientele. The economic down turn of the 1930s compounded the financial loss for bathhouses as wealthy philanthropists who once supported the PBA and the bathhouses of Philadelphia pulled their funding. Philadelphia’s public baths began closing through the 1940s; the Gaskill Street Public Baths, the crowning glory of the Philadelphia bathhouse movement, closed in 1942, and the PBA dissolved on January 11, 1950.

Through the twentieth century, as bathhouses faded from memory, public swimming pools and sea bathing became increasingly popular forms of public bathing. With an emphasis on recreation rather than public hygiene, the New Jersey shore is world famous for its sea bathing and boardwalk attractions, remaining the last bastion of public bathing for the Greater Philadelphia area in contemporary society.

Ryan D. Purcell is an M.A. candidate in American History with a concentration in urban culture at Rutgers University.

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University.