Vigilance Committees

Essay

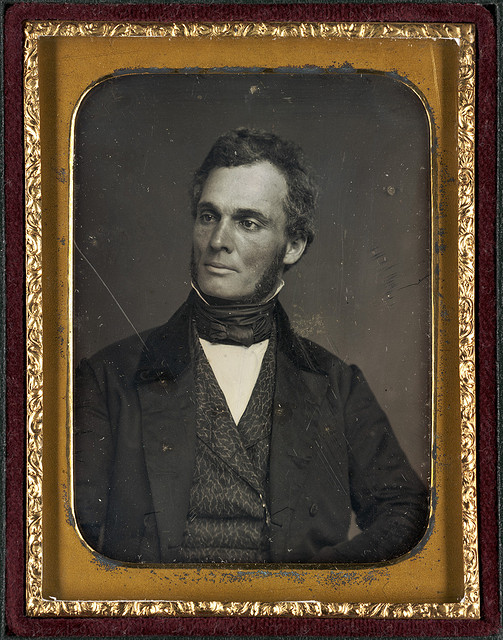

As Pennsylvania and other northern states became havens for enslaved people who sought to escape bondage, free Blacks and sympathetic whites organized Vigilance Associations, which operated Vigilance Committees (sometimes called Vigilant Committees) to protect fugitives and potential kidnap victims. After Black abolitionist David Ruggles (1810-49) formed the first such organization in New York City in 1835, Robert Purvis (1810-98) convinced his Philadelphia associates to do the same in 1837. Citizens in rural counties soon followed suit, and Vigilance Committees began to appear throughout the region. Women’s auxiliaries soon followed.

In the 1830s, a series of events highlighted the need for Philadelphians to organize a sustained initiative to help the runaways who were flocking to the region in increasing numbers. Angered from watching slave catchers chase down escaped slaves and free Blacks, a Committee of Twelve, which included Purvis, met in 1834 to consider helping fugitives escape. Two years later, Purvis became involved in a dramatic rescue of four enslaved brothers named Dorsey. Finally, under the direction of Purvis and his father-in-law, the influential businessman James Forten (1766-1842), a group of men met in August 1837 to organize the “Vigilant Association of Philadelphia,” with the primary goal of aiding fugitives and kidnap victims.

Members of the Vigilant Association paid twenty-five cents to join and contributed at least seventy-five cents yearly. They elected a Vigilant Committee of fifteen members and appointed officers, including a president, a secretary, a treasurer, a number of subcommittees, and a salaried agent to collect funds for their initiatives. Members chose James McCrummell (?-c1867), a prominent Black dentist, as president; Jacob C. White (1806-72) as secretary; and James Needham (?-1870) as treasurer. A year later, in July 1838, women formed the Female Vigilant Association to assist in fundraising. This group also had a committee of fifteen that included Elizabeth White (1807-?) as president. The women held West Indian Emancipation Day celebrations on August 1 and fairs in December to raise money.

Vigilant Committees communicated with each other through informal means and messengers, creating loose and irregular regional networks. Sometimes their efforts crossed state boundaries, but the details of their work is difficult to trace because participants concealed the evidence of their efforts to help enslaved people break the law by “stealing themselves” from their masters.

Vigilant committees operated more openly than the secretive Underground Railroad. The association’s and committee’s work was kept secret, but their existence was well known. In Philadelphia, members published their names and addresses in the Pennsylvania Freeman newspaper and in flyers so that fugitives and others in need could easily find them. Purvis’s home at Ninth and Lombard Streets contained a hidden room in the basement for emergencies, and his country home, Byberry (near Bristol in Bucks County), served as a temporary home for many. The committee also circulated flyers to enlist donations of clothing and other paraphernalia to help disguise fugitives and send them on their way to Canada and other points along the Underground Railroad.

Abolitionists affiliated with the Pennsylvania Abolition Society (PAS) and the Pennsylvania Antislavery Society (PASS) assisted the Vigilant Committee in many ways. John Greenleaf Whittier (1807-92), a New Englander who moved to Philadelphia in 1837 to edit the Pennsylvania Freeman (formerly known as the National Enquirer and General Register), helped to found the committee. David Paul Brown (1795-1872), a noted Philadelphia criminal attorney who worked with the PAS and helped to found the Philadelphia Antislavery Society, represented fugitives and the abolitionists who assisted them free of charge.

The Philadelphia Vigilant Association reorganized annually in 1839, 1840, and 1841, changing leadership and staff as it struggled for financial stability while offering increased services to fugitives. The group offered fugitives boarding, clothing, medical attention, legal counsel, and guidance farther north. In the six months from June to December 1839, the committee handled more than fifty cases and sent forty-six people to freedom. Most of these fugitives were from Virginia and Maryland, and most went to Canada via New York. Other destinations included Trinidad and England. By the fall of 1841, the group was handling more than three cases a week.

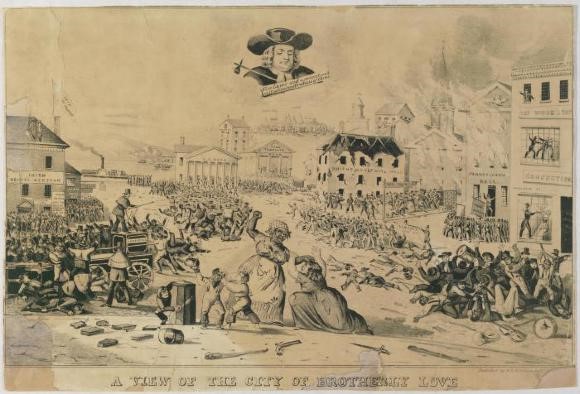

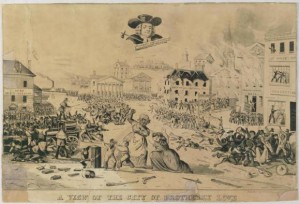

A race riot in Philadelphia on August 1, 1842–the latest in a series that occurred during the 1830s and 1840s–stifled the committee as rioters targeted the Purvis home, leading the family to relocate to their property in Byberry. With Purvis gone, the committee essentially ceased to function. Charles W. Gardner (1782-1863), pastor of the First Presbyterian Church, revived it in late December 1843 with the help of Black leaders Alexander Crummell (1819-98) and Hetty Reckless and white abolitionist J. Miller McKim (1810-74), a salaried agent of the Pennsylvania Antislavery Society. This effort met with limited success, however, due to a number of factors that included disagreements among Black and white abolitionists over the issue of direct resistance as the antislavery movement entered its more militant phase in the 1840s and 1850s.

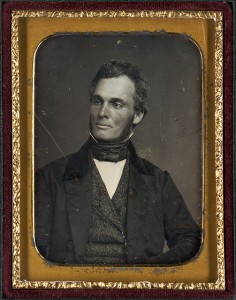

A final iteration of the Vigilant Committee emerged in December 1852 in response to the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law. Purvis came back to lead a new General Committee of nineteen and guide a new Acting Committee, which was chaired by William Still (1821-1902). Still, whose name became synonymous with the Philadelphia Underground Railroad, had been working as McKim’s assistant at the Pennsylvania Antislavery Society since 1847. This committee lasted about a decade.

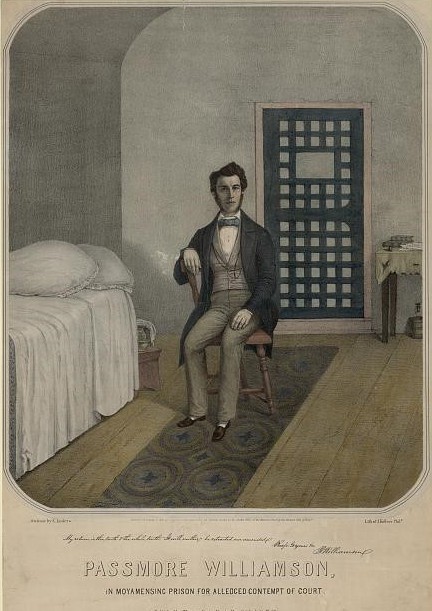

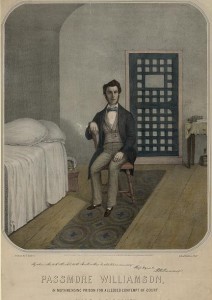

Perhaps its most famous action involved the efforts of Still and Passmore Williamson (1822-95) to rescue Jane Johnson (c1814-72). Johnson and her children were brought to Philadelphia by her owner, North Carolina politician and U.S. ambassador to Nicaragua John H. Wheeler (1806-82), in July 1855 as they made a side trip during their journey to South America. While in the city, Johnson approached local free Blacks about her desire to escape, and they reached out on her behalf to the Pennsylvania Antislavery Society for assistance. After learning of her request for assistance, Williamson, Still, and five Black dockworkers proceeded to the ferry where Johnson and Wheeler were, found her and the children, and helped them escape while holding the shocked slave owner at bay. Williamson, the only white involved in the bold rescue, served more than three months in Moyamensing Prison on charges of contempt of court for refusing to tell officials where they could find Johnson. Williamson’s imprisonment created a backlash that led many previously indifferent whites to embrace the antislavery cause. Two of the dockworkers who physically held back Wheeler served one week’s imprisonment for assault, but Wheeler eventually dropped the charges against Williamson and Still was acquitted of riot and assault charges.

Abolitionists active with the Vigilant Committees were the most radical among the nation’s antislavery leaders. They sought to work within the American political and legal system where possible to overturn slavery. At the same time, however, they remained willing to break the law if necessary to protect the rights of individuals in need of assistance.

Beverly C. Tomek is the author of Pennsylvania Hall: A ‘Legal Lynching’ in the Shadow of the Liberty Bell (Oxford University Press, 2013) and Colonization and Its Discontents: Emancipation, Emigration, and Antislavery in Antebellum Pennsylvania (NYU Press, 2011). She earned a Ph.D. in history at the University of Houston and teaches at the University of Houston-Victoria. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Compromise of 1850 (Library of Congress)

- The Struggle Against Slavery: The Abolition Movement and Underground Railroad in Pennsylvania (ExplorePaHistory.com)

- Abolitionist of Society Hill (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Abolitionist's Dreamland (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- The Liberation of Jane Johnson (Digital Exhibit, Library Company of Philadelphia)