Hog Island

Essay

Hog Island, at the confluence of the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers, exemplifies many broad trends in the environmental history of the region. Once improved for agriculture, the natural landscape ultimately deteriorated through overexploitation, leading to its conversion for industrial, commercial, and other forms of development. No longer productive in the early twentieth century, the island was buried in fill to create a featureless landscape suitable for industry and development.

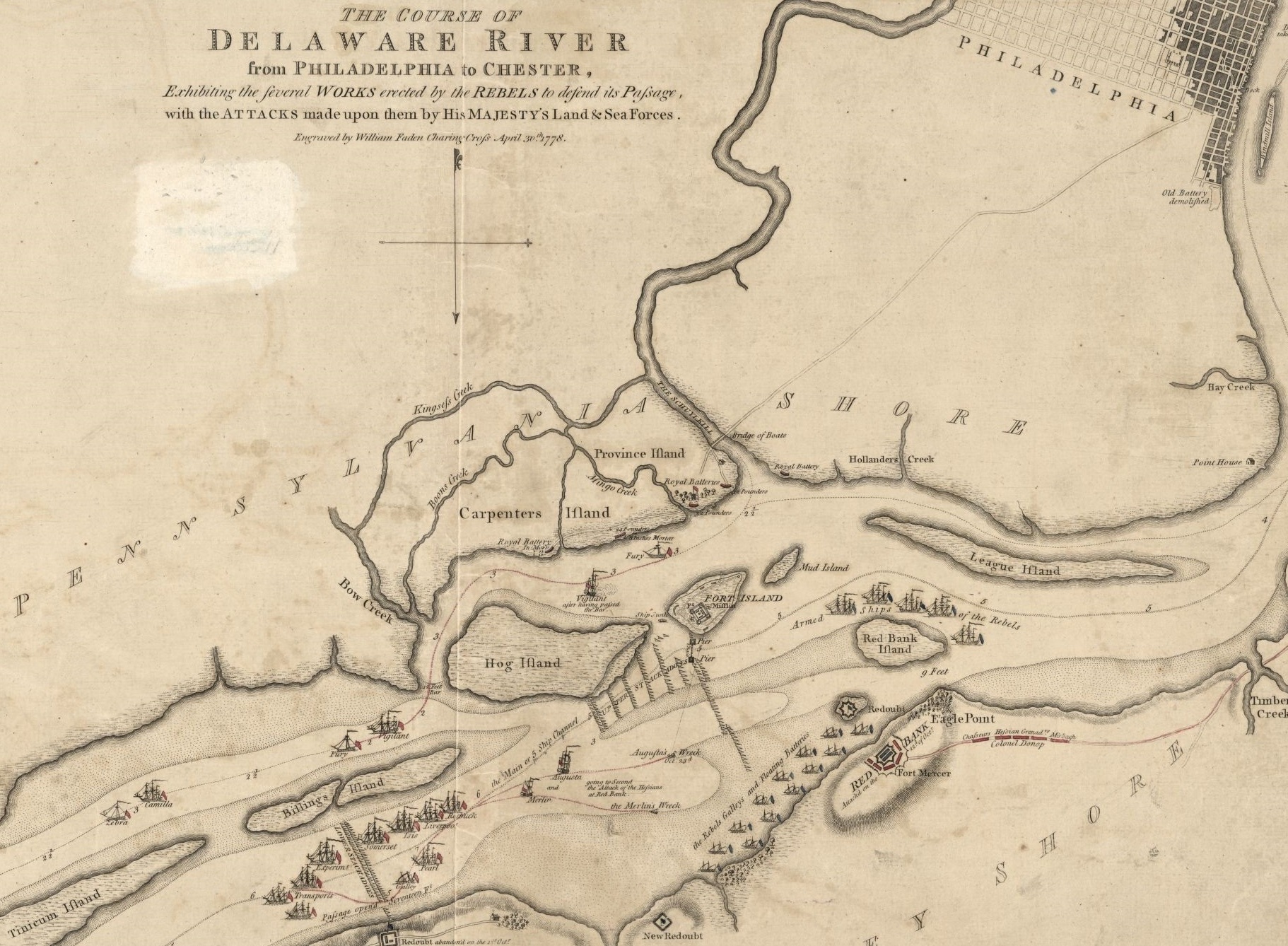

Swedish settlers began taking formal possession of the islands at the confluence of the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers between the 1640s and 1680s. Hog Island was not purchased from the Lenape by Swedish immigrant Otto Ernest Cock until 1681, the same year that William Penn (1644-1718) established the Province of Pennsylvania. This ushered in a period of agrarian use in which these rich riparian bottomlands and islands served the growing metropolitan center of Philadelphia. However, to make them productive required banking, or diking, to keep them from being flooded during high tide by brackish river waters.

Banking such extensive areas as Hog Island required substantial investments in labor and finances. It is not certain when the wetlands on Hog Island began to be reclaimed, but Hog Island was certainly diked by the outbreak of the Revolution, as an order to have it flooded was given by the Council of Safety as a measure against the invading British troops moving upriver toward Philadelphia in 1777. The island played no significant role in the Revolution, but the value of Hog Island as agriculturally productive land was affirmed by a nine-year (1780-89) legal battle over ownership after the conflict ended. By 1790, the island was advertised for rent and described as “200 acres of the richest maddow [i.e., meadow]” and by the first decade of the nineteenth century, 360 acres had been reclaimed by diking.

Island of Agriculture

Hog Island was used exclusively for agriculture for almost the entire nineteenth century.

By 1855, the island was owned by a single landowner, John Black, who lived in New Jersey. Mid-century newspapers indicate dairy and livestock raising were the principal agricultural activities on the island. By 1910, the island had only two owners, Charles Black and Francis Bohlen, and was divided into lots, which may have been rented to separate tenant farmers.

Hog Island’s ownership by absentee investors for half a century is the central fact in the fate of the island. By John Black’s admission years later, the island’s natural fertility had been ruined by the lack of maintenance. In 1894 the island’s owners contracted with the American Dredging Company to use the island as a dumping ground for dredge spoils from the Delaware River. This effectively ended about 200 years of agriculture on Hog Island and initiated a process that would end with the complete obliteration of the island as a distinct landform in the Delaware River. The American Dredging Company deposited sufficient river gravels and sands to raise about 300 acres of the island an average ten feet above its natural elevation.

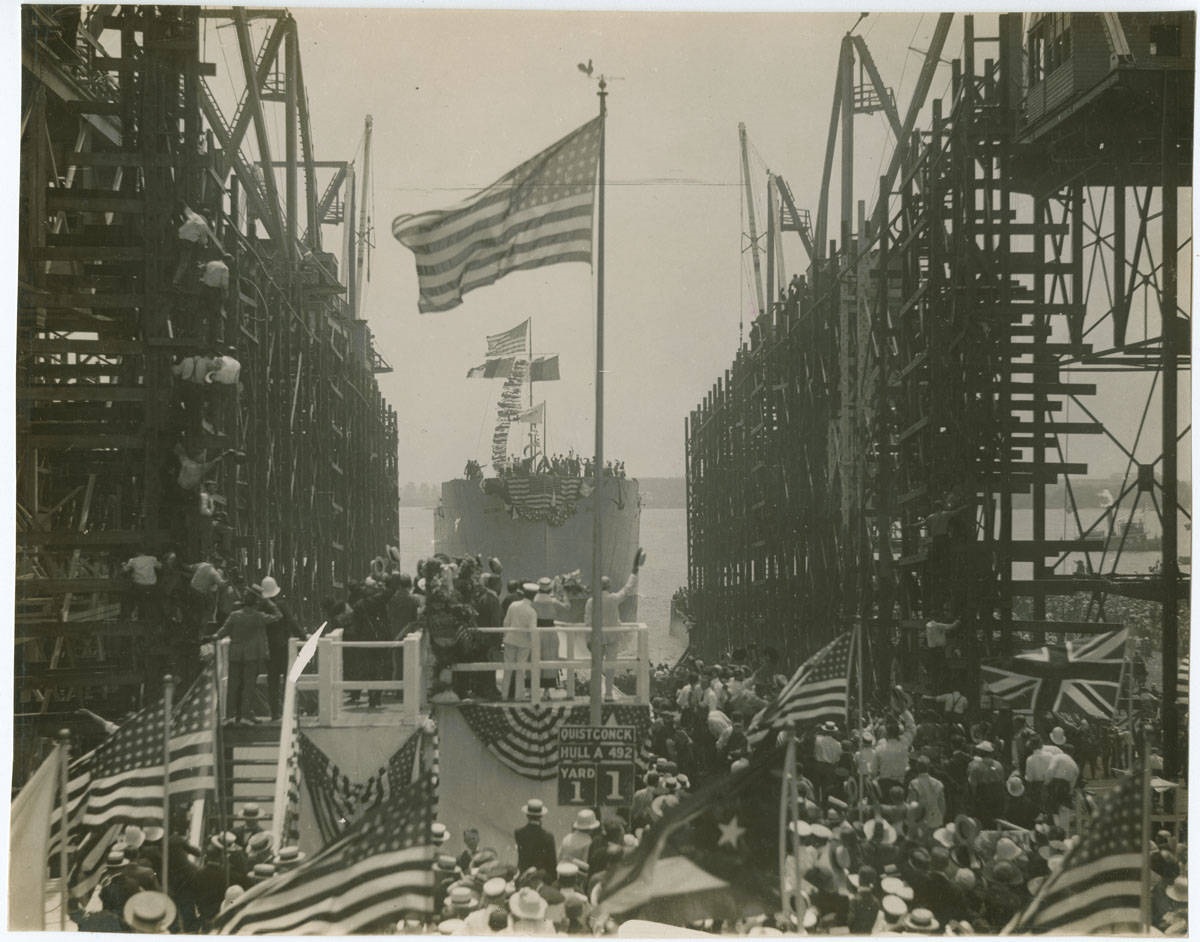

The final effacement of Hog Island and the creation of a new industrial landscape in its place came with the United States’ entry into World War I. Even before the United States entered the conflict, it was clear that the existing merchant fleet was inadequate to the task of supplying the Allies, much less sending troops. What the U.S. government needed was a new shipyard and a new approach toward shipbuilding to create the largest shipyard in the world. This new shipyard would convince allies and enemies alike that the United States was a world power and a force to be reckoned with.

Fill and More Fill for Shipyard

Hog Island–by 1916 a semiwasteland of dredge spoils–provided an ideal opportunity to create the planned industrial shipbuilding facility. Additional filling was required to provide an adequate platform on which to erect the yard, and over half a million cubic yards of fill was added to the site between 1918 and 1919. The new shipyard had no electricity, sewage facilities, adequate roads, or rail service; all these utilities had to be installed.

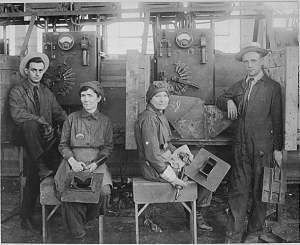

Construction of the Hog Island Shipyard began in December 1917 and the labor force reached over 35,000 by the time it was completed in the spring of 1918. Not only did Hog Island become the largest shipyard in the world, but new mass-production construction methods were used. Hog Island was not a shipyard in the traditional sense, but rather an assembly center where parts manufactured elsewhere would be riveted or welded together to create a series of identical freighters.

The Hog Island Shipyard was completed just months before the war that had made it possible ended. The yard had cost $65 million to build, but despite that investment and arguments made for maintaining it, the Hog Island Shipyard was closed after completing its last ship in 1921. When the shipyard closed, only 122 ships had been built in the largest shipyard in the world.

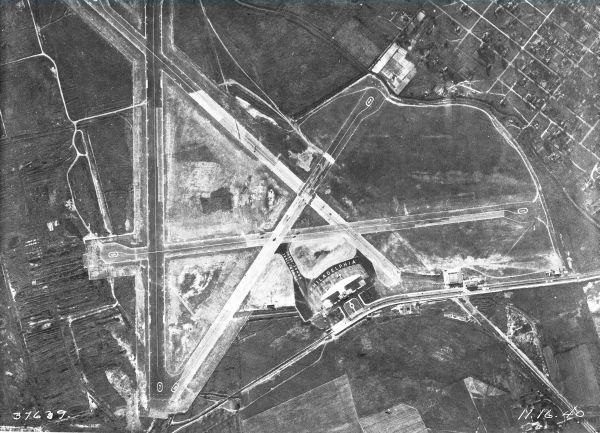

In March 1930, the City of Philadelphia purchased the abandoned shipyard for $3 million. The city, with financing from the Works Progress Administration, used a portion of the former shipyard and about 600 acres of Tinicum Township to build the Philadelphia Muncipal Airport. Additional dredge spoils were were added to the property before landing strips and terminal building were constructed. The new airport opened for commercial air traffic in 1940. Additional in-filling of the former Hog Island was performed in the mid-1950s in support of post-war airport expansion.

A portion of the former island not taken for the airport was converted into an ammunition port in 1940. Following the end of World War II, the Hog Island marine terminal continued to be used for loading ordnance until the ammunition depot closed about 1958. Since then, it has been used as a marine petroleum discharging terminal, first by Gulf Oil and later by its successor, Sun Refining and Marketing Company.

Hog Island shared the fate of many riparian environments across the urbanized northeastern United States. Exploited until no longer profitable, the island disappeared under a mantel of industrial development. No longer visible, it has been divorced from its own history as place in Philadelphia’s natural and cultural landscape.

John W. Lawrence received his Master’s Degree in Anthropology from the University of Pennsylvania in 1989. He serves as Senior Archaeologist for an international engineering firm and has conducted original archaeological and historical research in Central America and in the Mid-Atlantic region. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Beachcombing By the Airport

- From Shipways to Runways: the Transformation of Hog Island, Part One (PhillyHistory.org)

- From Shipways to Runways: the Transformation of Hog Island, Part Two (PhillyHistory.org)

- From Wetland to Urban Land: A Social and Environmental History of Philadelphia's Tidal Islands (PhilaPlace.org)

- Hog Island Shipyard: Context and Discoveries