Schuylkill Expressway

Essay

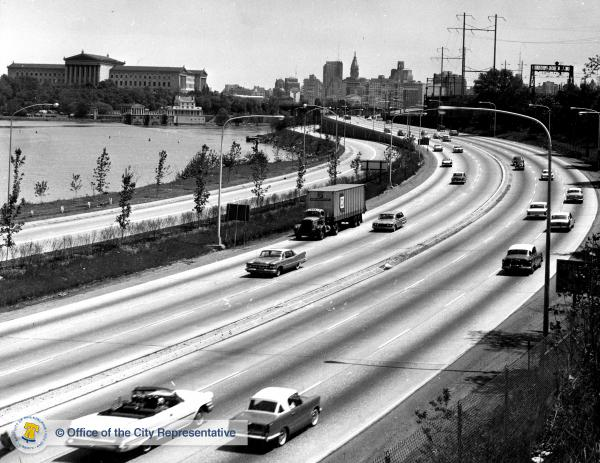

Fully opened for traffic November 25, 1958, Philadelphia’s Schuylkill Expressway was gridlocked from the first day of its operation. Envisioned by city planners as a panacea for economy-suffocating urban traffic congestion, but built on flawed engineering assumptions about traffic flows, the expressway ignored any concern for postwar social and regional realities. Rather than being acclaimed, within years the highway was decried, ignominiously branded the “Surekill Distressway.”

Decades before it was built, traffic jammed the narrow streets of 1930s Philadelphia despite the Great Depression, and later the city’s World War II-fueled economic revival only exacerbated matters. Postwar pro-growth planners and organizations such as the Greater Philadelphia Movement (GPM) and the Citizens’ Committee on the City Plan (CCCP) saw this automobile congestion, together with slums and suburbanization, as draining the city’s lifeblood. Well-engineered express highways, they argued, would save the downtown and help restore livable urban neighborhoods.

Highway mania had intensified in 1938 with publication of “Toll Roads and Free Roads,” prepared by the Bureau of Public Roads (BPR). Created in 1918 to free American farmers from the mud, the engineering-oriented BPR in 1938 now advocated a modern urban-oriented highway system that one year later was rendered graphically in General Motors’ “Futurama” exhibit at the 1939 New York World’s Fair.

After World War II, Philadelphia boosters rallied behind the idea of modern freeways and pressed for a submerged Vine Street Expressway to relieve congestion from traffic flowing into the city from New Jersey via the Benjamin Franklin Bridge. However, Pennsylvania’s historically anti-urban state legislature, which controlled both state and federal highway funds, quashed the idea. Instead, momentum built in Harrisburg for an east-west arterial highway in 1947 called the Valley Forge Expressway, connecting Philadelphia with King of Prussia and designed to relieve traffic jams on U.S. Route 30, which served Philadelphia’s “Main Line” suburbs such as Ardmore, Bryn Mawr, and Haverford. Talk of such a highway dated from the 1920s and appeared in the 1931 Regional Plan of the Tri-State Regional Planning Federation.

By 1941, the year that President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Interregional Highway Commission proposed a 33,920-mile, federally funded interregional highway system (the Federal Aid System), the so-called Valley Forge Expressway appeared on Pennsylvania’s wish list of modern state highways. Together with the widened and submerged Vine Street and the “Industrial Highway” skirting the Delaware River, the Schuylkill Expressway was featured in planner Edmund Bacon (1901-2005) and architect Oscar Stonorov’s (1905-1970) spectacular “Better Philadelphia Exhibit” in 1947.

With the Pennsylvania Turnpike nearing completion, Philadelphia’s fledgling City Planning Commission in 1947 undertook the Philadelphia-Camden Origin and Destination Survey, whose data officially supported building an express highway following the Schuylkill River from the new Pennsylvania Turnpike exit at Valley Forge into the “heart of Philadelphia.”

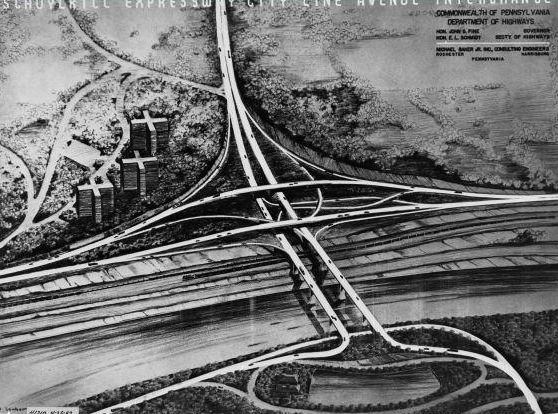

However, while both the Bureau of Public Roads and Edmund Bacon saw the Schuylkill Expressway relieving traffic congestion regionally, north and south of the proposed multilane highway, as well as east and west, Clark, Rapuano, Holleran, Hardesty, and Hanover, the engineering firm contracted to design the roadway, interpreted the 1947 origin-and-destination data to alleviate mainly Pennsylvania Turnpike and Philadelphia-generated traffic volumes. They ignored Broad Street traffic and other traffic flowing from Philadelphia’s burgeoning northeast where Bacon planned garden-city communities. Nor did Clark, Rapuano’s flawed design grapple any more successfully with the topographical obstacles presented by the rugged, albeit idyllic, Schuylkill Valley terrain as it entered the city limits. Against protest, the historic Schuylkill canal locks and sections of Fairmount Park were sacrificed, and the narrowing of the roadway from six lanes to four as the highway approached Thirtieth Street made a bottleneck inevitable, despite frequent and dangerous turnoffs into Fairmount Park.

Constructed between 1950 and 1959, much of it before the availability of federal funds derived from the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, the original Schuylkill Expressway largely predated modern highway standards. By 1962, fatal accidents occurred frequently, and experts identified ten potential deathtraps. In 1970, with federal funds, the state completely redesigned and rebuilt the complex of on- and off-ramps in the vicinity of City Line Avenue and the Roosevelt Boulevard Extension. In the 1980s, the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation added new lanes and rebuilt shoulders along the entire eighteen-mile length of the highway. Long the busiest highway in Pennsylvania, by the twenty-first century the expressway carried 163,000 vehicles daily within Philadelphia County and 109,000 more vehicles daily in adjoining suburban Montgomery County. Its heavy use profoundly impacted the growth of the Philadelphia region. It especially opened the city’s western suburbs to intensive residential and industrial development, making Montgomery County, for example, a center of American pharmaceutical industrialism and boosting one of the largest shopping-mall complexes in America at King of Prussia. That intense growth, plus the traffic from North Philadelphia and Bucks County flowing from the Roosevelt Boulevard Extension of the expressway, daily flooded the highway with commuter vehicles. Thus, notwithstanding several rebuildings, the Schuylkill Expressway in the era 2010-2014 still ranked as one of the most dangerous and congested commuter highways in America. Its historic failings attest to the flawed motivations and assumptions that guided its birth.

John F. Bauman is Visiting Research Professor at the Muskie School of Public Service, University of Southern Maine, and the author of books and journal articles on a broad range of urban policy issues. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History