Cast Iron Architecture

Essay

Over a period of four decades, from 1840 through 1880, a commercial district of distinctive cast iron buildings developed in Center City Philadelphia. Born of the iron wealth of Pennsylvania and fashioned by the city’s architects and mechanics at a time of technological innovation, these buildings helped define the downtown of the emerging modern city. Clustered along the city’s main commercial streets, from the Delaware River waterfront to Twelfth Street between Arch and Pine Streets, this architectural phenomenon became largely invisible due to extensive rebuilding, but notable examples of cast iron buildings survived into the twenty-first century.

Before the eighteenth century, cast iron was scarce and expensive. This changed with innovations in England beginning in 1709, when Abraham Darby (1676-1717) leased a furnace in Shropshire and produced cast iron with coke, a distillate of pit coal. By 1720, Darby and other iron masters could produce cast iron of such reliable quality and at a reasonable cost that it became a common material for steam engine cylinders. In Pennsylvania, the discovery of vast iron and coal resources in the western part of the state prompted major iron production in places like Hopewell, Cornwall, and Phoenixville.

During the succeeding decades, cast iron opened new structural and aesthetic possibilities for a range of products, including rails, columns, and iron bridges. The first cast iron bridges, built in England, became that nation’s most notable transportation structures. In buildings, cast iron structural columns added a fireproof element to support timber or wrought-iron beams. By the end of the eighteenth century, cast iron became a familiar material for an increasing number of architectural and engineering purposes, including decorative balconies, railings, verandahs, fences, and window grills, both in Europe and the United States. In England and elsewhere in Europe, cast iron was used for domes, train sheds, greenhouses, and libraries. Its ability to replicate shapes and forms inspired new systems of production and design.

Early Cast Iron Buildings of the Pre-Civil War Era

As the nation’s second city and a major center of population and wealth, Philadelphia quickly developed new ways to use such a promising new material. The climate of technological innovation in the city together with the role of the Franklin Institute and its scientific Journal of the Franklin Institute in disseminating these advances helped to spur new uses.

Philadelphia architects and engineers who traveled to England observed the range of uses of cast iron in buildings. In the 1820s, William Strickland (1788-1854) visited England and upon his return used cast iron columns and wrought iron railings in the U.S. Naval Asylum on Gray’s Ferry Avenue. In 1830-31, architect John Haviland (1792-1852) employed flat cast iron plates that resembled ashlar masonry on the façade of the Miners Bank building in Pottsville, Pennsylvania. The international success of the Crystal Palace building to house the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, followed by a similar building in New York City the next year, provided strong endorsement for the building material in substantial and even monumental buildings.

Thomas Ustick Walter (1804-87) drew from his experience as an architect in Philadelphia when he selected cast iron for the new dome on top of the United States Capitol building in Washington, D.C. Constructed from 1855 to 1866, the U.S. Capitol dome resembled the wood and stone dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. Walter’s design of the dome using cast iron followed his use of decorative cast iron in the design of the portico columns for the Chester County Court House. Thus, the U.S. Capitol dome can be seen as an expression of Philadelphia’s cast iron industry.

Cast iron’s ready availability coincided with Philadelphia’s need to develop a new type of commercial building with large expanses of glass windows to display products and allow more sunlight into the buildings’ interiors. Cast iron structural columns made higher ceilings possible, and, thus, larger display windows. These qualities allowed merchants to be more competitive in a downtown where commercial functions were becoming increasingly separated from residential and industrial uses. Commercial enterprises tended to cluster together in order to benefit from comparison shopping.

Commodius Interior Spaces

The earliest cast iron buildings in Philadelphia, most dating from the late 1840s, had partial cast iron facades at the first floor level or store fronts. Cast iron columns freed interiors from bulky wooden or granite piers and provided commodious interior spaces. This decade also marked expansion for cast iron production. By the late 1840s, Philadelphia’s foundries were disseminating cast iron products beyond the city’s boundaries. In a Southwark foundry, Merrick and Town produced iron rafters for the 1849 Brooklyn Gas House. In Kensington, Reaney, Neafie & Co. manufactured prefabricated iron warehouses in 1849 intended for California.

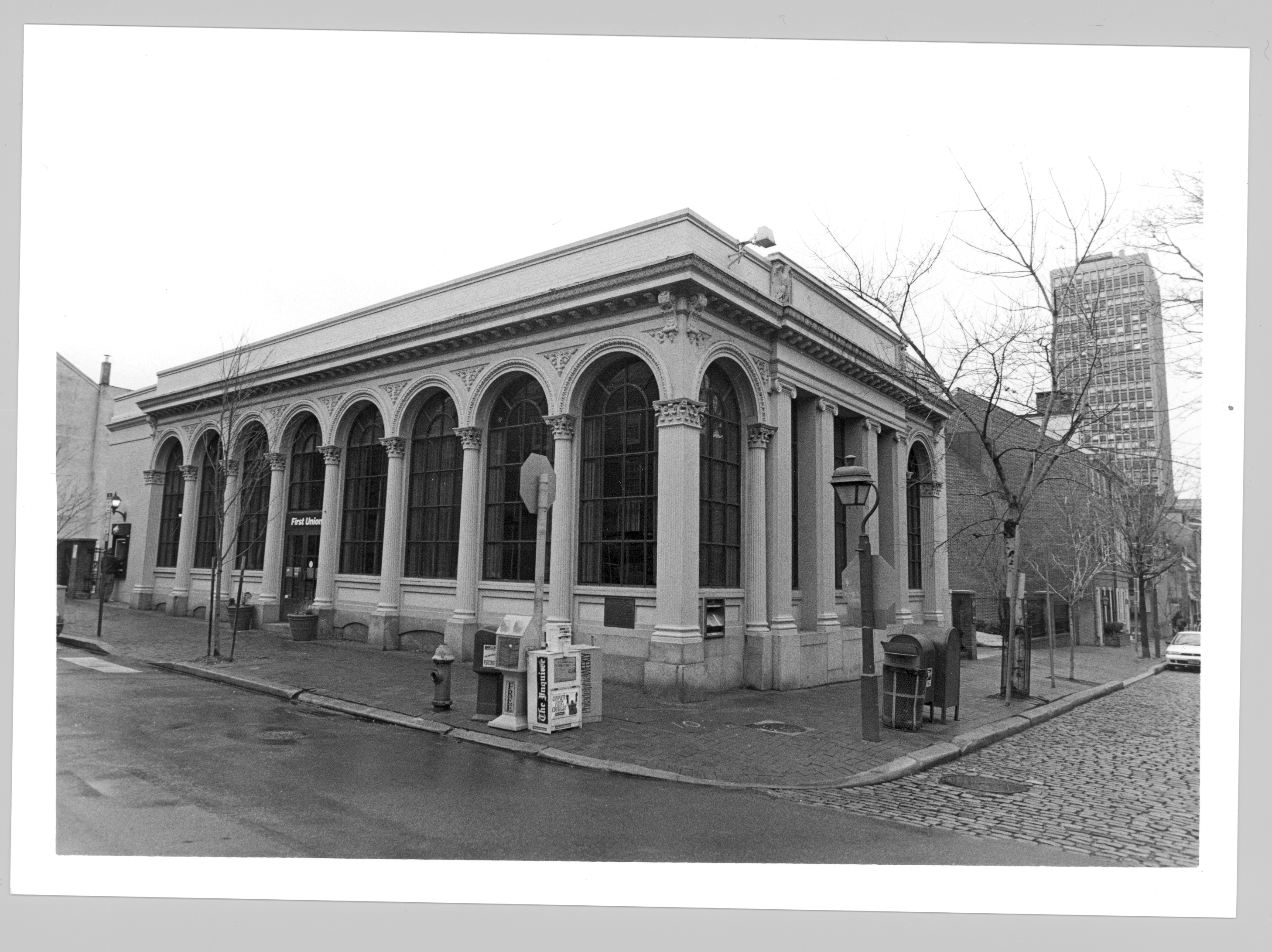

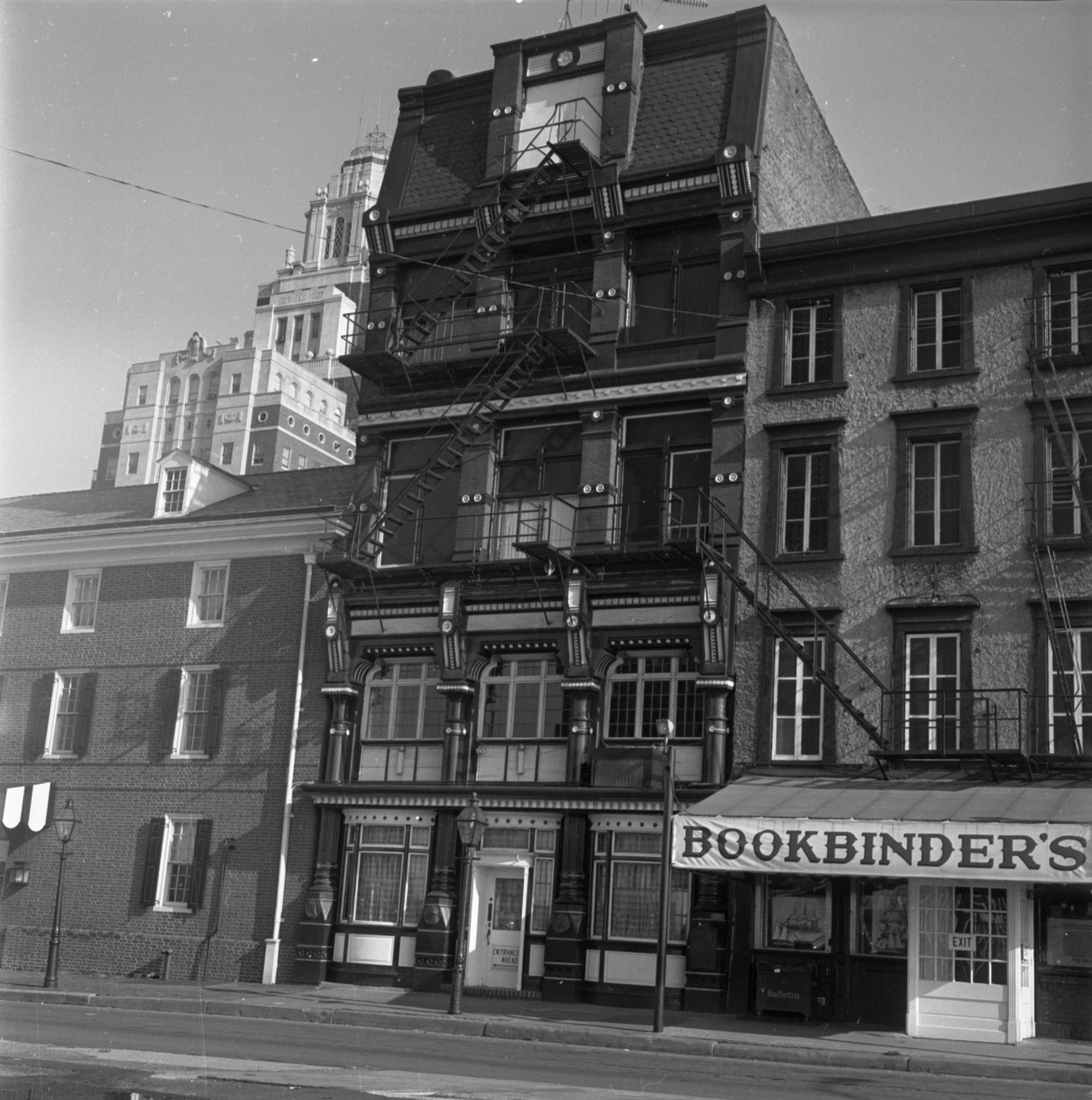

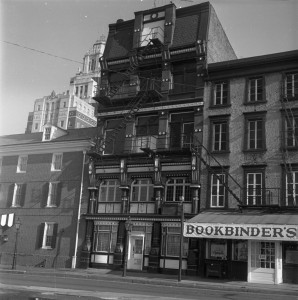

In the following decade, cast iron reached its full potential in furnishing complete cast iron facades. The iron facades of this decade rose three and four stories, their interior space often supported by cast iron columns and girders, with little visual obstruction. In addition, cast iron was used in pre-cast arches for spanning major interior spaces. For example, architect John Gries (1827-62) used cast iron beams “placed in tension by massive steel cables to span the great banking room” in the Farmers’ and Mechanics’ Bank at 427 Chestnut Street. The great plasticity of cast iron also permitted ornamentation in the form of emblems, shields, medallions, and even sculpture. Architects and builders devoted great effort to make finished façades resemble marble or another stone.

During the 1850s, Philadelphia architects including Samuel Sloan (1815-84), Joseph C. Hoxie (1814-70), and Stephen D. Button (1813-97) designed cast iron buildings, although their practices also included masonry and brick buildings. Some architects, like John Riddell (ca. 1814-73), specialized in designing cast iron buildings during this decade. In addition to columns and lintels in commercial buildings, cast iron was used in flat plates to resemble stone blocks on building exteriors. Cast iron allowed for the addition of lavish ornamentation, including animal heads, ornate window lintels, and rosettes.

The crowning glory of the city’s cast iron buildings of the 1850s was an office building at 503-507 Chestnut Street (since demolished). Designed for client William M. Swain (1809-58), the building by John McArthur, Jr. (1823-90), also architect of Philadelphia’s City Hall, was designed as a general office building to house a variety of organizations and businesses. Its cast iron elements were provided by New York architect and founder James Bogardus of New York City. Four stories high, the top of the building featured sculptures representing historical figures, including George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Faust, and Johannes Gutenberg. For many years after the building’s demolition, several of these statues stood inside the Free Library of Philadelphia.

The easy replication of cast iron elements allowed similar buildings to be designed for the Sun Building in Baltimore of 1851 and the Harpers Brothers Printing Plant of 1854 in New York City. Bogardus provided the iron for all three buildings, although each was credited to a different architect.

Nationwide and Beyond

By the end of the 1850s, Philadelphia foundries shipped cast iron elements to all parts of the nation and beyond, marking a breakthrough in traditional regional barriers in architecture and decorative arts. The network of designers, founders, and clients presented a complex picture of the diffusion of ideas and designs. The firm of Robert Wood & Company shipped its wares to Caracas, Venezuela. Merrick & Son of the Southwark Foundry sent a cast iron light house to Florida. The firm of H. C. Oram & Co. supplied iron front buildings for New Orleans, Savannah, and Nashville. Stephen Decatur Button designed an iron front building for the Central Bank Building in Montgomery, Alabama. During this period, Philadelphia became a leader in the design and production of cast iron building components.

The Civil War disrupted the city’s industrial economy in the 1860s and halted major architectural projects as factories turned their attention to meeting wartime needs. By the early 1870s, when construction projects resumed, cast iron was no longer a novel building material and it was unlikely that architects would return to the aesthetics of the earlier decades. They continued to use cast iron in building facades, structural elements, and decorative feature, but in modern forms.

Instead of using cast iron to imitate the appearance of stone, designers turned toward cast iron buildings with slender columns in facades, thereby allowing for large expanses of glass, while the buildings remained structurally sound. They experimented with nonmasonry paint colors to highlight cast-iron design elements. In interiors, thin cast iron structural elements allowed for height, light, efficiency, and more floor space. Because of the advent of the elevator in 1857, buildings could rise to even greater heights—five and even six story buildings. Some architectural historians have identified the use of cast iron in buildings of this decade as a precursor to the all-glass curtain walls of the twentieth century.

During the 1870s, two architects dominated the design of these buildings: John McArthur Jr. and Addison Hutton (1834-1916). McArthur designed cast iron facades with narrow cast iron columns that allowed for iron to look like iron. Iron elements were finished buff and gold. For interiors, McArthur arranged tall narrow cast iron columns running along the longitudinal center of the building to allow natural light to stream in. Retail interiors of this type responded to the needs of businesses that offered a wide variety of products. By separating products into sections, designers provided the basic organization of the department store in its infancy. Addison Hutton designed buildings described as “iron offices,” which symbolized the safe conditions for exhibiting and examining imported china, queensware, and other luxuries.

1876: Centennial Exhibition

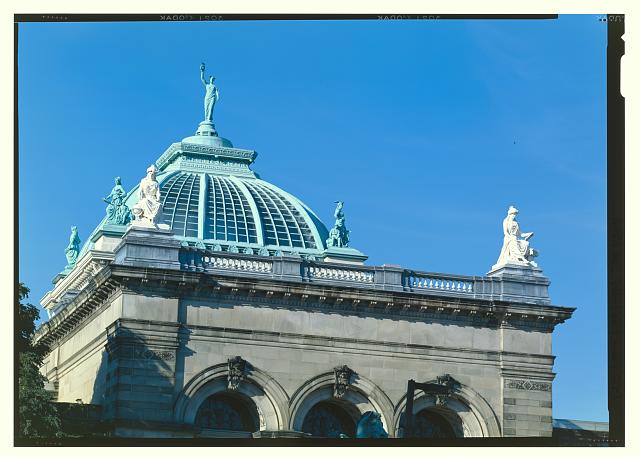

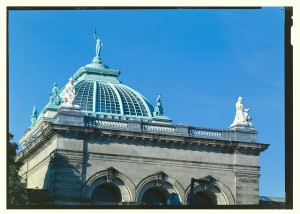

The Centennial Exhibition, held in Philadelphia in 1876, highlighted Philadelphia’s key role in the nation’s industrial progress with buildings incorporating cast iron. The exposition’s chief architect, Hermann J. Schwarzmann (1846-91), designed Memorial Hall with a granite façade topped with a glass and iron dome. (In 2008, this building became home to Philadelphia’s Please Touch Museum.) Another exposition building, Horticultural Hall, resembled a gigantic greenhouse, facilitated by an iron and glass roof to provide wide exhibition spaces. This building was demolished in 1955 after being damaged the preceding year during Hurricane Hazel.

During the 1870s, at least five major iron foundries filled Philadelphia’s cast iron requirements. They included Morris, Tasker & Co.’s Pascal Iron Works, John A. Gendell’s Architectural Iron Company, H. C. Oram & Co., Sanson & Farrand, and Samuel J. Creswell & Co. Only Morris, Tasker and Creswell continued after 1879, marking a decline in the use of cast iron in architecture and a turn toward new building materials, including steel and terra cotta. In addition, iron foundries outside of the city, most notably James Bogardus’s New York foundry, supplied ironwork for some of the city’s cast iron buildings and others nationwide. These foundries and others advertised in city newspapers and issued pamphlets, brochures, and catalogues promoting the superiority of their products to building clients, architects, and engineers.

By 1880, a concentration of cast iron buildings stretching from the Delaware River west to Broad Street, built in a matter of 40 years, stood as testament to Philadelphia’s technological innovations and cultural status in the mid-nineteenth century. The experiments that began in Philadelphia in the pre-Civil War era to apply the newly abundant cast iron as shop fronts and structural elements gradually became accepted building practice in Philadelphia and the nation’s other urban centers. Shoppers flocked to the city’s commercial center and peered into display windows as establishments adopted this innovation in building design and clustered in continuous rows of iron fronts along Philadelphia’s major commercial streets. Interior spaces expanded and reached upward to new heights, providing shoppers with a succession of commercial displays and shopping opportunities above the ground floor.

Over the last decades of the nineteenth century and into the early twentieth century, building clients demanded even taller buildings, beyond what cast iron facades and structural elements could withstand. As a granular material, cast iron could become unstable and buckle under stress. In the 1880s, Chicago architects experimented with steel beams and columns as structural elements and masonry cladding on the exteriors, leading to development of the nation’s earliest “skyscrapers.” Architectural innovation from the emerging urban centers of the nation’s Midwest region led to the decline in the use of cast iron in Philadelphia’s commercial architecture and coincidentally to a decline in the city’s reputation for building innovation.

Antoinette J. Lee is an independent historian in Arlington, Virginia. Previously, she worked at the National Park Service, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and as a historic preservation consultant. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University