Penn’s Landing

By Dylan Gottlieb | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

Penn’s Landing, a 35-acre redevelopment site between Columbus Avenue and the Delaware River and South and Vine Streets, was designed to attract visitors to Philadelphia’s waterfront. Since construction began in the early 1960s, the vision for Penn’s Landing has evolved from a public space devoted to historic and museum facilities, to a locus for private development, to an arts and entertainment venue. For decades, a series of grand plans were proposed and then discarded, leaving the site only partially developed. In the 2010s, however, Penn’s Landing was poised to undergo a total transformation—which, when completed, promised to restore its connection to the urban grid, enliven its recreational spaces, and catalyze commercial development.

In 1682, the area that became Penn’s Landing was the site of William Penn’s arrival in Philadelphia. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it sat at the center of Philadelphia’s waterfront. Ferries carried passengers across the Delaware River to growing towns in southern New Jersey. Dockworkers unloaded boats laden with cotton, liquor, and sugar. Produce streamed up from the river along city streets to the nearby Dock Street Market.

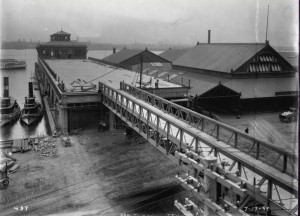

By the middle of the twentieth century, however, activity along the waterfront slowed. Ferry service ended after the opening of the Delaware River (later Benjamin Franklin) Bridge in 1926. Larger highway-bound trucks had difficulty accessing the piers via narrow city streets. Existing docks were too small to accommodate bigger ships that carried goods inside massive shipping containers. By 1956, only six of the central Delaware River’s twenty-three piers were still operational.

In the mid-1950s, the city began to buy up sections of abandoned waterfront property with the intent of clearing it for redevelopment. In 1961, the Philadelphia City Planning Commission announced ambitious plans for the site, which would be expanded into the river with landfill. Beginning at the Benjamin Franklin Bridge and running south for a “nautical mile” along the Delaware, the plan included a twenty-five- to thirty-story tower at the foot of Market Street, two boat basins, a restaurant, thousands of parking spaces, hotel and commercial buildings, an embarcadero for cruise ships, a museum devoted to Philadelphia’s waterfront history, and a new home for the Academy of the Natural Sciences. The city’s Department of Commerce hired Philadelphia architect and University of Pennsylvania professor Robert Geddes (b. 1923) as its design consultant; he called for the $85 million development to be completed in time for the Bicentennial in 1976.

A Shift in Emphasis

Work on the project proceeded slowly. In 1962, demolition began on the dilapidated waterfront piers. Next, a 3,000-foot-long bulkhead was built several hundred feet offshore and filled with earth. Workers laid new sewer and electric connections. After eight years, the site was finally graded and prepared for development.

As the site was readied, the city’s redevelopment officials shifted the emphasis of the project away from public spaces towards revenue-generating commercial and real estate-oriented development. To spearhead this new direction, the city granted control of the site to in the late 1960s to the Old Philadelphia Development Corporation, which had been formed to oversee the restoration of Society Hill. In 1970, OPDC in turn spun off the project to the newly-formed nonprofit Penn’s Landing Corporation (PLC). A semigovernmental corporation, PLC’s board of elected city officials and downtown business figures administered publicly owned lands on the waterfront and oversaw renewal efforts at Penn’s Landing over the next four decades.

The head of the new PLC, Girard Bank chairman Stephen Gardner (1921-1978), worried that the existing Geddes plan devoted too much space to historic ships and museums, putting Penn’s Landing in danger of becoming “a static historical monument.” He called instead for revamped plans with more hotel, office, and apartment buildings. Those new plans, prepared by the design firm of Murphy, Levy & Wurman, dramatically expanded the area devoted to private development. The square footage of office space increased by a factor of eight; 250 new apartment units would be built in a series of thirty-story residential towers. Planners anticipated that the revamped $100 million design would yield several million more dollars in tax revenue than the abandoned Geddes plan.

In the early 1970s, the ongoing fight over the construction of I-95, its ramps, and a covered highway cap near the Society Hill neighborhood put this new plan on hold. Meanwhile, the city installed a more modest set of improvements in anticipation of the Bicentennial: a pedestrian promenade, sculpture garden, a boat basin for historic ships, and a maritime museum. More than two million visitors came to Penn’s Landing during the festivities. When the controversy over the I-95 ramps was finally settled in 1977 (with highway traffic directed onto Delaware Avenue), PLC once again requested proposals for a Penn’s Landing master plan. Several plans were accepted then subsequently withdrawn due to lack of interest from private developers.

Great Plaza Opens

While PLC continued to solicit site plans throughout the 1980s, construction began on public amenities that were intended to spark private development. The $10 million Great Plaza, an open-air amphitheater with terraced seating for 5,000 people, opened in 1986 after years of construction delays and funding shortfalls. Beginning in 1982, a trolley car carried visitors the length of Penn’s Landing during warm-weather weekends and holidays. These improvements, however, did not entice a developer to commit to a large mixed-use project on the site. In the mid-1980s, the renowned Rouse & Associates firm expressed interested in building one million square feet of office space along with commercial and residential units. But the company withdrew its offer before construction could begin, claiming that its analyses forecast insufficient rental income. In 1989, New York developer Daniel Rose (b. 1930) proposed a similar large-scale project; it too was scrapped when recession struck in 1991.

When Mayor Edward Rendell (b. 1944) came to office in 1992, he shifted PLC’s focus away from master plans towards immediate market-driven development. According to former PLC chairman Stanhope Browne (1932-2013), Rendell pushed planners to stop asking “ ‘how do we get the best kind of design’ to ‘how [do we] get a deal done soon?’ ” Rendell hoped to bring in suburban visitors to the site by building a centerpiece family-oriented entertainment attraction. In 1997, Rendell announced developers’ designs for a massive $130 million complex that resembled a shopping mall—complete with retail, restaurants, and a movie theater. But cost overruns and outcry over the destruction of public spaces led the developer to abandon the project in 2002. The Delaware River Port Authority’s plans to connect Penn’s Landing and Camden with an aerial tram across the river also collapsed. Marketed under the slogan “two cities, one exciting waterfront,” the failed project was typical of their quixotic efforts to build tourism through coordinated bistate planning. After spending roughly $16 million on the tram, an abandoned concrete tower was left to show for it.

Reimagining Penn’s Landing

By the 2000s, neighborhood, planning, and public-interest groups began to express their displeasure at the degree of control developers held over the future of Penn’s Landing. In 2002, a coalition of civic organizations asked Mayor John F. Street (b. 1943) to allow for public input on future plans. In 2003, Penn Praxis, the public engagement arm of the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Design, held a series of public forums on Penn’s Landing. The several hundred residents that attended these events agreed the site should prioritize recreational space and riverfront access over commercial development. In 2006 (after a series of delays including a federal corruption probe into the PLC), the Street administration turned over all riverfront planning responsibilities to a new advisory group, with PennPraxis acting as its chief design consultant.

In 2009, Mayor Michael Nutter (b. 1957) created the Delaware River Waterfront Corporation (DRWC) to replace PLC and direct the holistic improvement of the riverfront from Oregon to Allegheny Avenues—a seven-mile stretch that included Penn’s Landing. DRWC promised to balance commercial and public spaces in a planning process that allowed for community input. In 2011, DRWC released its first master plan for the riverfront. Shortly thereafter, it revealed a Penn’s Landing study which called for caps over I-95 and Columbus Boulevard from Chestnut to Walnut Street to improve pedestrian access to Penn’s Landing. DRWC’s proposed $250 million project would create two new public spaces: a four-acre plaza built atop the cap over I-95 and Columbus Boulevard and a gently-sloping 7.5 acre park that would extend to the edge of the Delaware River. DRWC would also invest in new bike and pedestrian trails. As DRWC pursued funds for the project, it created seasonal programming to bring visitors to Penn’s Landing—a summer pop-up park at Spruce Street and “summerfest” and “winterfest” attractions at the riverfront skating rink. With the plan under discussion, the future of Penn’s Landing remained uncertain. Yet again, the site was poised somewhere between wholesale renewal and repeated disappointment.

Dylan Gottlieb is a Ph.D. candidate at Princeton University, where he works on recent American urban history.

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Waterfront study says $250-million Penn's Landing investment would return $1.6 billion (WHYY, October 15, 2015)

- Will new ways to experience Olympia keep the cruiser afloat? (WHYY, August 9, 2016)

- Kenney budget puts $90 million toward Penn's Landing park capping I-95 (WHYY, February 27, 2017)

- Delaware River Waterfront Corporation's first president looks back and ahead (WHYY, July 12, 2017)