Superfund Sites

By Stephen Nepa

Essay

As a region with a complex industrial history that generated numerous chemical, industrial, and landfill operations, by the late twentieth century Greater Philadelphia held some of the nation’s highest concentrations of environmentally hazardous “Superfund” sites. Named for the federal Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA), also known as “Superfund,” the designation of such sites led to penalties and cleanup enforcement, although some cases became mired in years (or decades) of costly litigation.

Congress and the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) created the Superfund following the discovery of 21,000 tons of buried toxic waste at Love Canal, New York, in 1978. The Superfund program imposed legal penalties on “potentially responsible parties” for generating pollution and forced those parties to pay (even retroactively) all or portions of a site’s remediation costs. After citizens, state agencies, or the EPA proposed sites for the Superfund registry, priority was determined by location (proximity to water, population, and/or wildlife), severity and level of contaminants, estimated cleanup costs, and the number or profiles of potentially responsible parties. If authorities found extreme environmental hazards, a site could be added to the National Priorities List and qualify for federal assistance.

Locally, chemical companies, manufacturing interests, oil refineries, and other industries had operated for many decades with few environmental regulations. The waste generated from those industries (and its disposal) created plumes of toxicity throughout Greater Philadelphia. When the Love Canal disaster occurred, its national profile alerted citizens and politicians to the potential for environmental dangers closer to home. Especially active in responding were congressmen and U.S. senators from New Jersey. U.S. Rep. James Florio (b.1937), a Democrat, authored the Superfund legislation and famously joked that cleaning all of his state’s sites would require “1,000 years.” (The EPA later estimated that cleaning New Jersey’s 235 trash dumps would require one-third of the $500 million initially allocated for the Superfund.) In 1983, Democratic Senators Bill Bradley (b.1943) and Frank Lautenberg (1924-2013) helped defeat a Republican-led proposal to eliminate the program after 1985. Bradley and Lautenberg, along with Pennsylvania Republican Senators Arlen Specter (1930-2012) and John Heinz (1938-91), helped to increase cleanup funds from $1.6 to $3.2 billion and extend the program through 1990.

More Than 200 Superfund Sites

Inventory of the toxic sites in the Philadelphia region began in the early 1980s, and by 2015 the region had more than two hundred designated Superfund sites in various stages of cleanup. Philadelphia County had the most sites (forty-four), followed by Montgomery County, Pennsylvania (thirty-four), and New Castle County , Delaware (twenty-nine). In 2014, Philadelphia ranked as the nation’s second-most polluted county in the nation, and New Castle County contained more sites than many U.S. states. New Jersey ranked first among all U.S. states for Superfund (and National Priorities) sites. By 2015, the six New Jersey counties closest to Philadelphia (Camden, Burlington, Gloucester, Salem, Cumberland, and Mercer) contained sixty-five Superfund sites. Camden County, with fifteen known sites across 227 square miles, ranked as South Jersey’s most polluted per capita.

Many of the region’s first sites to be placed on the National Priorities List were dormant landfills that posed immediate threats to soil and groundwater. In 1982, the Tybout’s Corner Landfill in New Castle, Delaware, judged as the nation’s second-most dangerous dumpsite, became that state’s first National Priority property. Tests of nearby Pigeon Creek and Red Lion Creek, which received municipal and Stauffer Chemical’s illegally deposited waste in the late 1960s and early 1970s, found more than twenty known carcinogens. With more than 100,000 people relying on nearby aquifers, the EPA in 1985 installed new water lines so that residents who had been dependent on contaminated wells could draw public water. After nine years of legal proceedings and cleanup, Tybout’s Corner came off the National Priorities registry in 1995.

In a similar case, the former Lipari Landfill at Pitman, New Jersey, termed by a state environmental activist as “the nation’s number one toxic waste site,” received National Priorities List designation in 1983. From 1958 until 1971, trash and liquid waste had been placed in hastily dug pits without lining. By the late 1960s, toxic runoff was seeping into nearby Alcyon Lake, leading to its closure for recreational use. Worse, the landfill lay above the Cohansey Aquifer, which runs under a large portion of South Jersey. With the EPA monitoring cleanup (paid for by Lipari’s primary operator), the site came off the National Priorities List in 1995; a new Alcyon Lake Park, with athletic fields and picnic areas, opened in 1999. Several other former landfills, including Strasburg (Coatesville, Pennsylvania), Moyer’s (Eagleville, Pennsylvania), and Fort Dix (Pemberton, New Jersey) also were added to the list in the early 1980s.

Chemical Industry Sites

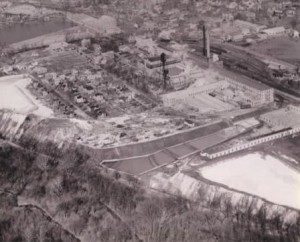

Several Superfund sites resulted from Greater Philadelphia’s chemical industry. In 1980, the EPA received an anonymous tip regarding several fifty-five gallon drums on a former dairy farm in Evesham, New Jersey. The later discovery of 300 illegally stored drums, many leaking trichloroethylene (TCE), prompted more than three decades of extraction, groundwater pumping, and soil remediation. In 2013, the EPA projected the site needed three additional years of cleanup before it could be deleted from the National Priorities List. In 1987, a multialarm fire at the vacant Publicker Industries site in Philadelphia beneath the Walt Whitman Bridge revealed 850,000 gallons of alcohol, antifreeze, cleansers, and PCB-contaminated oil. Later judged as the city’s worst Superfund site, cleanup of the thirty-seven acres was completed in the 1990s. The infamous “white mountains” of asbestos in Ambler, Pennsylvania (piled as high as ninety feet), generated by Keasbey and Mattison Company into the 1970s, once meant jobs and prosperity. A decade later, with high rates of mesothelioma in the suburban town, the piles made the National Priorities List. By 2015, with cleanup completed, regular soil testing continued on the undeveloped fifty-five-acre site. In Newport, Delaware, home to DuPont and other chemical firms for more than a century, a twenty-two-acre landfill bisected by the Christina River contained lead, cadmium, zinc, mercury, and other toxic substances. After the site’s placement on the National Priorities List in 1982, the EPA and DuPont completed remediation in 2002; in 2013, the rehabilitated site was converted into a solar generating station.

In addition to the National Priorities Sites, dozens of others with less severe contamination were retrofitted under the Superfund program and continued to operate with periodic assessments by the EPA or state-level environmental agencies. These included shipyards, oil refineries, landfills, salvage yards, and rail facilities. In 1988, after removal of PCBs and more than 6,000 tons of debris, the Philadelphia Navy Yard was deleted from the Superfund list. By 2015, the fifty-seven-acre site hosted not only a naval maintenance facility but also new offices and green spaces. South Philadelphia’s Energy Solutions (formerly Sunoco) refinery, the largest on the East Coast, received citations in 2013 for violating air quality despite infrastructural updating. Camden’s Conrail-Pavonia Yard, South Jersey’s busiest for freight trains, remained an active Superfund site in 2015.

Though several of the area’s most severe Superfund sites were remediated by the 2010s, others still required extensive sanitizing and monitoring. Many that remained active, such as Camden’s Harrison Avenue landfill and Marcus Hook’s East Tenth Street sludge lagoons, were located in poor, politically disadvantaged neighborhoods where cleanup procedures languished for years. Yet as Greater Philadelphia’s economy after the 1990s depended less on heavy industry and environmental regulations became stricter, the possibilities of future contamination decreased.

Stephen Nepa received his M.A. from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and his Ph.D. from Temple University. He teaches history at Temple University, Rowan University, and Moore College of Art and Design. He also has appeared in the Emmy Award-winning documentary series Philadelphia: The Great Experiment. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Delaware County Plant Added to List of Superfund Priority Sites (WHYY, March 13, 2012)

- N.J. dealing with mountains of Sandy debris (WHYY, November 19, 2012)

- Former Deptford landfill could become a major solar farm (WHYY, September 6, 2013)

- Penn researchers get $10 million grant to study asbestos in Ambler (WHYY, June 11, 2014)

- Asbestos cleanup in Ambler nears completion (WHYY, October 6, 2014)