Barnes Foundation

Essay

Businessman, chemist, educator, and art collector Dr. Albert C. Barnes (1872-1951) established the Barnes Foundation in 1922 as a center for art education organized around his growing collection of paintings, sculpture, and furniture. The institution earned international renown, less for its pedagogy than for its art collection, which by mid-century was world-class. Initially based in the Philadelphia suburb of Merion, the foundation famously and controversially moved its galleries to a new campus on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway in Center City Philadelphia in 2012. This act completed the foundation’s transition from inwardly oriented school to publicly oriented cultural institution.

Barnes’s successful career in the pharmaceutical industry laid the groundwork for his foundation. He built a fortune manufacturing Argyrol, a widely used antiseptic that he developed with German chemist Hermann Hille (1871-1962). While running a factory in West Philadelphia to produce the drug, Barnes introduced the study of philosophy into his employees’ daily schedule. With advice from painter William Glackens (1870-1938), who knew Barnes from their days attending Central High School, Barnes began collecting art to use in his lessons. He launched his foundation with the goal of expanding these experiments in art education.

Barnes actively shaped every aspect of his fledgling organization. In the most tangible sense, he donated his art collection and a recently purchased plot of land in Merion to the foundation. The foundation’s charter and bylaws outlined the terms of these gifts and enumerated detailed guidelines that governed the foundation’s operations. He commissioned noted Beaux-Arts architect Paul Philippe Cret (1876-1945) to design the institution’s facilities. The foundation’s building, programs, and art collection additionally reflected Barnes’s ongoing interest in African American culture, which grew out of his fascination with music and religious ceremonies he encountered as a child. At times Barnes pursued partnerships with other schools and exhibition spaces in the region, but the foundation remained independent during his lifetime.

Education at the Barnes Foundation began as a pedagogical experiment in the systematic study of art. Barnes believed that learning to look carefully and methodically would grant students access to a deeper, more enriching experience of art. His theory of art education combined concepts of intelligence from psychologist William James (1842-1910), studies of aesthetics from George Santayana (1863-1952), and a philosophy of education and social reform pioneered by John Dewey (1859-1952). Dewey’s work was so influential that he was named honorary director of education at the foundation in 1923. Students read texts by these and other thinkers while they learned to visually dissect artworks with particular regard for what Barnes called “plastic form” – line, color, light, and space. In contrast to conventional practices, this technique downplayed other aspects of an artwork such as the artist’s intention, the story told by an image, and the historical circumstances surrounding an object’s creation.

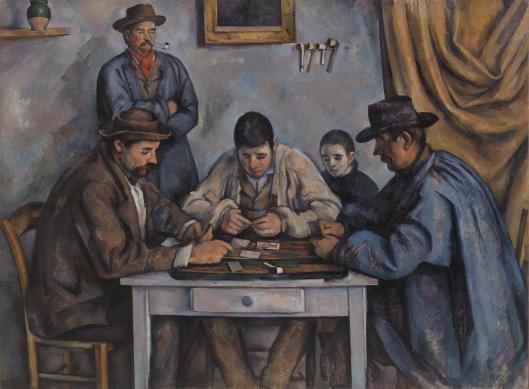

To hone their visual analysis skills, students studied the eclectic objects that hung in the foundation’s galleries. These eventually included masterworks by European modernists such as Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) and Henri Matisse (1869-1954), over a hundred African sculptures from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and the largest known array of paintings by Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919). It also featured works by American artists Barnes knew personally, such as Glackens, Charles Demuth (1883-1935), and Horace Pippin (1888-1946). To illustrate various lessons, Barnes installed these items in “wall ensembles”: complex, often symmetrical arrangements of artworks, metalwork (like hinges and dental tools), and in some cases, furniture. The composition of the wall ensembles invited viewers to look for visual connections across objects rather than study each piece individually. Diverging from contemporary exhibition trends, Barnes did not group objects by artist, culture, or historical period. Instead he mixed and matched, disconnecting the items on display from any context other than his galleries. Throughout his lifetime, Barnes reconfigured the wall ensembles to draw out new connections across objects.

Many of the education and exhibition practices at the Barnes Foundation reflected Barnes’s desire to change Philadelphia’s cultural landscape by providing a new model for experiencing art. He asserted that his institution offered a necessary alternative to the region’s art establishment, which he repeatedly criticized for its conservative tastes, elitism, and frivolity. His work, too, was the subject of frequent critique. For example, paintings from his collection met with mockery when exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1923.

Even so, the impressive collection eventually attracted extensive positive attention from scholars, art collectors, and other individuals not affiliated with the foundation. Members of the public who wanted to visit the collection were required to write to the foundation and request an appointment. Although Barnes welcomed many outsiders into his galleries, he notoriously denied access to several prominent individuals including author James A. Michener (1907-97), collector Walter P. Chrysler (1909-88), and art historian Meyer Schapiro (1904-96). Illustrative of Barnes’s strong personality and sharp tongue, some who were refused admission to the collection received rejection letters signed by Barnes’s francophone dog. Critics accused Barnes of leveraging his galleries as a tool for spurning people he did not like or whose elite social status he resented. Barnes maintained that for the sake of the school he only permitted visitors who were interested in the serious study of art.

When Barnes died unexpectedly in a car accident on July 24, 1951, the guidelines he developed for the foundation’s long-term operations took effect. As outlined in the foundation’s bylaws, these instructions ranged from a proscription against moving the paintings after he and his wife died to a plan for transferring leadership. Initially, his wife Laura (1875-1966), director of the foundation’s arboretum since 1928, became president. Education programs continued under the direction of Violette de Mazia (1896-1988), Barnes’s longtime assistant who had played a vital role in developing much of the curriculum. After Laura Barnes died, trustee Nelle E. Mullen (1883-1967) assumed the leadership position. Following her death, stewardship of the foundation began to shift from the original trustees to Lincoln University, a historically Black university in nearby Chester County, which became responsible for appointing new trustees to the foundation’s board as positions opened.

With the exception of occasional lawsuits and financial challenges, the foundation operated quietly for four decades after Barnes’s death. It reemerged in the public eye in 1990, when newly appointed director Richard Glanton (b. 1946) initiated a series of changes aimed at improving the foundation’s fiscal viability and public image. Although the bylaws provided specifications for how the foundation should function when Barnes could no longer lead the organization, they provided limited options for raising the revenue required to maintain the foundation’s activities. By 1990 the galleries required substantial renovations and the foundation did not have sufficient funds to cover the cost of the project. To raise money for the endeavor, the foundation obtained permission from the Montgomery County Orphans’ Court to send selected works from the collection on an international tour while the galleries closed for renovations. Judge Louis Stefan (1925-94) determined that a one-time deviation from the prohibition against moving the paintings would be permissible in order to ensure the foundation’s future success. Between 1993 and 1995 an exhibition of European masterworks from the collection traveled to the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo, the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, the Art Gallery of Ontario, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Haus der Kunst in Munich, earning unprecedented attention for the collection and, in several cases, for the institutions that hosted the tour, as well.

When the collection returned from the tour and the galleries reopened in Merion in November 1995, the foundation faced new challenges. More visitors than ever flocked to see the now-famous art. Although a local ordinance limited the number of weekly visitors the foundation could host, the newfound attention created problems in the neighborhood. It brought an abundance of tourists onto a residential street, and the traffic upset neighbors. The foundation tried to ameliorate the situation by building a parking lot to accommodate the cars and tour buses, but neighbors protested this action, as well. Conflict over the increased traffic resulted in an expensive lawsuit that left the foundation unable to pay its legal bills and maintain operations under its financial model. Recognizing the hostile local context and financial challenges that it faced, foundation leaders explored the possibility of moving the galleries from Merion to Center City Philadelphia, where, they argued, the institution could better accommodate visitors and fundraise more effectively. At the same time, the foundation also sought court permission to expand its board from five members to fifteen members in order to broaden its adviser base and enhance its ability to raise funds and fulfill its mission.

Major Philadelphia philanthropists and political leaders backed these endeavors. Critics, including arts writers and Barnes alumni, vehemently protested against relocating the collection. They argued that it belonged in Merion because Cret’s galleries, the arboretum setting, and the historical context in which it had been displayed for decades were vital to the full experience of the collection. Others challenged the proposed board expansion, arguing that such an act would shift control of the foundation into the hands of powerful individuals and organizations that Barnes had vied with during his lifetime. The foundation’s lawyers argued that moving the collection and expanding the board was the only way that it could maintain operations. Although Judge Stanley R. Ott granted permission for these changes in 2004, the foundation was enmeshed in legal battles and waves of conflicting public opinion for nearly another decade as a group of neighbors and former students led repeated challenges to the judge’s ruling both within and beyond the courts. During that period the Barnes Foundation became an important case study for scholars and practitioners in a range of fields including philanthropy, nonprofit management, museum studies, and trust and estate law.

Despite the efforts of those who opposed the move, the Barnes Foundation expanded onto a new campus on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway in Philadelphia, which opened to the public in 2012. At that time the Merion campus became dedicated primarily to horticultural programs. The 4.5-acre Philadelphia campus is located in a tourist district near the Franklin Institute, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Academy of Natural Sciences, and the central branch of the Free Library of Philadelphia. With a building by Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects and landscape design by Olin, it speaks the language of public institution, not domestic enclave. In addition to its permanent collection galleries, which resemble the historic Merion setting and preserved Barnes’s wall ensembles, the Parkway facilities include special exhibition galleries and visitor services beyond what was feasible in Merion. The foundation expanded its education programs to offer lessons for school groups in partnership with the School District of Philadelphia, and it provides both traditional and new courses for adult learners. The move cemented the foundation’s shift from primarily serving its regular students to directing its efforts toward a broad cross-section of the public. In turn, city leaders touted the Barnes on the Parkway as an important contribution to Philadelphia’s rich constellation of cultural offerings that elevate the city’s status in the eyes of national and international audiences.

Laura Holzman is Assistant Professor of Art History and Museum Studies at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University