Plays of Susanna Rowson

Essay

In the three years in the 1790s that Susanna Rowson (1762-1824) was a presence on the Philadelphia stage as a writer and performer, her tireless promotion of the theater helped establish its centrality to the city’s arts community. Rowson came to prominence as a writer for Charlotte Temple: A Tale of Truth, published in 1791 in England and in 1794 in America and considered America’s first best-selling novel. While Rowson is more footnote than noted innovator in the history of American drama, her importance to theater in Philadelphia cannot be overstated.

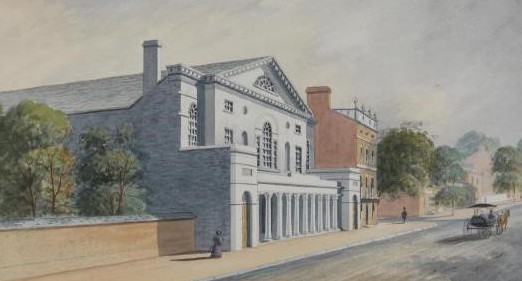

In the summer of 1793, Philadelphia theater impresario Thomas Wignell (1753-1803) went to London to recruit ensemble members for his New Theatre then under construction near Sixth and Chestnut Streets. There he met Rowson, a minor, but established, novelist and actress, who had recently returned from performing in Edinburgh with her husband of seven years, William. Rowson had lived in America as a child, when her naval officer father was stationed in Massachusetts. Although her family endured a period of imprisonment during the Revolutionary War on account of her father’s Royalist loyalties, she had enough happy memories from her childhood on the east coast that she was keen to return. She and her husband accepted Wignell’s offer and sailed to Philadelphia aboard the George Barclay later that summer. She remained with Wignell’s company until the fall of 1796, when she left to join the Federal Street Theatre in Boston, where she spent one season before retiring from the stage to embark on a teaching career.

More a solid ensemble player than top-billed actress, Rowson performed in classic and contemporary works while affiliated with Philadelphia’s New Theatre (later renamed the Chestnut Street Theatre). Notably, she was also an author, penning for the stage the comedic melodramas Slaves in Algiers; or, a Struggle for Freedom (1794) and The Female Patriot; or, Nature’s Rights (1795); the opera The Volunteers (1795); and The American Tar, or the Press Gang Defeated (1796).

The three-act ballad opera Slaves in Algiers—promoted as a comedy, but containing characterizations emblematic of federalist melodrama—premiered at the New Theatre on June 30, 1794, with Rowson playing the part of Olivia, one of the few times she appeared as a romantic lead. Olivia jeopardizes romance in an effort to seek the release of her enslaved father, espousing Christianity at every step. Rowson said in the preface of the printed edition that she borrowed elements from Don Quixote, but Rowson biographer Ellen Brandt finds that it bears more than a passing resemblance to a subplot in Rowson’s anonymously published novel The Test of Honour (1789). As Brandt notes, its “glorification of American patriotism and the nobility, honor, and resourcefulness of the American people” is all encompassing, as is its “special interest in the rights and liberties of women,” something that can be said for all of her plays and many of her novels. A particularly scathing review of Slaves in Algiers by William Cobbett (1763-1835), under the pseudonym “Peter Porcupine,” brought attention to the play and was notorious for its personal attacks against Rowson, whose sincerity as a republican woman he called into question.

The sting of Cobbett’s review remained with Rowson throughout her years in Philadelphia. Her public replies to him included one in the preface to her epistolary novel Trials of the Human Heart, which was published the following April. She did not address Cobbett by name in the preface, but referred generally to “a kind of loathsome reptile” that places himself among writers and critics when in fact he lacks “the qualifications necessary to [be] either.” Rowson wrote that one such reptile “has lately crawled over the volumes, which I have had the temerity to submit to the public eye,” referring to his attacks on both Slaves in Algiers and Rebecca. She proceeded to trace her love of America and its people back to her childhood in a manner reflective of the melodramatic style of her plays.

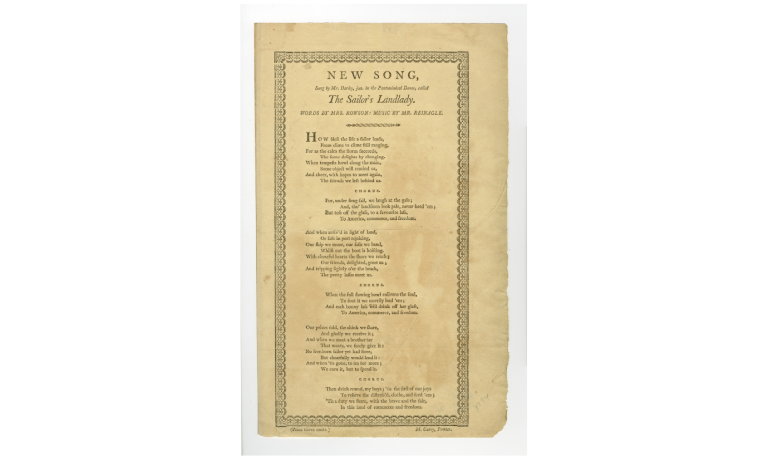

The ballad opera The Volunteers made its debut at the New Theatre on January 21, 1795. Only the score—with words by Rowson and music by the Anglo-American composer Alexander Reinagle (1756-1809)—survives. As with her earlier play, Rowson once again chose to reference political events for her plot. This time, however, she chose one closer to home: the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794, in which farmers protested the new American government’s imposition of a distilled spirits tax to help pay off debts incurred during the Revolutionary War. In July 1794, a federal tax official’s home was attacked by western Pennsylvanian farmers and President George Washington (1732-1799) sent over 10,000 militiamen, who successfully suppressed the uprising. This play, as with her other political works, reflected her support of the federalist project. As with Slaves in Algiers, Rowson exhibited a predisposition for combining tragic events with musical comedy, and, once again, it was well received by Philadelphia audiences.

Fewer details are known about her other plays, The Female Patriot and The American Tar, or the Press Gang Defeated, but it is a safe assumption that both were adaptations of earlier British works. Rowson scholar Patricia Parker finds The Female Patriot to be a reworking of the Philip Massinger (1583-1640) play The Bondman (1624), and The American Tar possibly based on a work by Jacob Morton. The Female Patriot premiered at the New Theatre on June 19, 1795, with Rowson in the role of Statilla in this ballad opera. Rowson’s contributions to The American Tar, which premiered at the New Theatre on June 17, 1796, are unclear. The program note describes this as a “ballet ‘founded on a recent fact at Liverpool.’ ”

Rowson established a much wider reputation as a writer only after leaving Philadelphia for Boston, the city in which she would reside until her death in 1824. She retired from the stage there in 1797, but the continued success of Charlotte Temple and her role as an educator of young women fortified the reputation she first enjoyed in Philadelphia.

Elizabeth Mannion’s publications on modern drama include The Urban Plays of the Early Abbey Theatre: Beyond O’Casey (Syracuse University Press, 2014).

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University