Contractor Bosses (1880s to 1930s)

Essay

As Philadelphia expanded physically after its 1854 consolidation of city and county, building contractors wielded a greater degree of political power as they paid politicians and civil servants handsomely for the rights to construct the city’s infrastructure. The late nineteenth century saw the emergence of the “contractor boss”—a construction magnate who wielded political power directly rather than through intermediaries. Reformers bemoaned the rise of a “contractor combine,” which dominated Philadelphia politics from the 1880s to the 1930s and enriched itself on overpriced deals that cost taxpayers millions of dollars annually.

Like many American cities, Philadelphia experienced astonishing growth after the Civil War in terms of population, geographic expanse, and wealth. As the city grew into an industrial powerhouse, every year larger portions of the municipal budget were pledged to infrastructure for the fast-growing metropolis: street paving, gas and water mains, sewers, docks, schools, hospitals, public transportation, and large-scale civic projects. Philadelphia’s expansive spirit was symbolized by the new Public Buildings, or City Hall, at Broad and Market Streets. When its cornerstone was laid on July 4, 1874, Philadelphia City Hall was projected to become the tallest building and most luxurious municipal structure in the world.

This period also saw the emergence in Philadelphia of an omnipotent Republican machine known as the Organization, which controlled nearly every elected and appointed political office. Philadelphia became a one-party city: between 1891 and 1915, the Democratic vote withered from 39 percent to less than 4 percent. The Organization devoted itself to maintaining its power base and enriching its leaders, often at the expense of Philadelphia taxpayers. More than 90 percent of city employees were forced to make illegal “voluntary contributions” to the Organization, adding more than $3 million to its coffers between 1903 and 1913. In 1904, journalist Lincoln Steffens (1866-1936) pronounced Philadelphia “the worst-governed city in the country.” While “all our municipal governments are more or less bad,” Steffens conceded, “Philadelphia is simply the most corrupt and the most contented.”

Widespread Graft

Philadelphia’s new seat of government became a symbol of its entrenched corruption and the influence wielded by well-connected contractors. Thanks in part to widespread graft, construction on City Hall dragged on for three decades, while its cost spiraled from $10 million to more than $24 million. When the by then outmoded Second Empire structure was declared complete in 1901, it was dismissed by essayist Agnes Repplier (1855-1950) as “that perfect miracle of ugliness and inconvenience, that really remarkable combination of bulk and insignificance.”

Soon after its inception, the Republican Organization found powerful allies among builders willing to pay for the privilege of participating in big-budget projects like City Hall. In the 1870s, political boss David Martin (1845-1920) began to recruit Irish Catholic contractors into the Republican Party, until then a bastion of Protestantism. Israel W. Durham (1854-1909), one of Martin’s rivals, formed an alliance with John Mack (1852-1915), head of numerous paving companies and later president of the Keystone Telephone Company. Thanks to Durham, Mack’s businesses acquired municipal contracts worth $33 million.

Martin and Charles A. Porter (1839-1907) became two of the first men to straddle the worlds of private enterprise and municipal service as true contractor bosses. During the 1880s and 1890s, while Martin served in various state offices and Porter was a state senator, they joined forces with John Mack to form the “Hog Combine,” so called because “they hogged everything in sight and more.” Martin and Porter’s Vulcanite Paving Company received 888 contracts valued at over $6 million, while other companies controlled by Porter were awarded contracts worth more than $2 million. Among the projects handled by the Hog Combine were the paving of Broad Street and the construction of the East Park and Queen Lane Reservoirs.

By the early twentieth century, two political blocs run by competing “contractor kings” battled to control the Republican Organization. State Senator James P. “Sunny Jim” McNichol (1864-1917), whom historian Dennis Clark (1927-93) called “the first Irish Catholic to become a top Republican potentate in the Philadelphia firmament,” ran the northern half of the city. McNichol’s interests included the Filbert Paving and Construction Company, which earned $3 million in city contracts between 1903 and 1911, and the Penn Reduction Company, a garbage-collection business with annual contracts in excess of $500,000. His Keystone State Construction Company handled contracts for the Market Street Subway, the Torresdale water filtration plant, and the Northeast Boulevard, Philadelphia’s first major parkway. Later renamed the Roosevelt Boulevard after Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919), the parkway’s original straight route was remapped to zigzag through land parcels acquired by Organization members, who sold them to the city at exorbitant markups. After McNichol was awarded a $1.4 million contract to build the boulevard, reform politician Rudolph Blankenburg (1843-1918) dubbed the enterprise the “McNichol Boodle-vard.”

A Trio of Vare Brothers

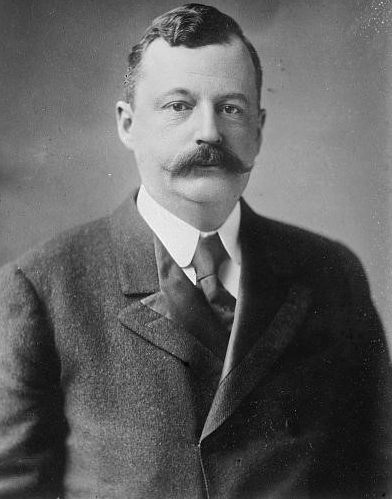

South of Market Street, the three Vare brothers ruled: George (1859-1908), Edwin (1862-1922), and William (1867-1934). Born to a poor family in the marshy wasteland known as the “Neck,” the “Dukes of South Philadelphia” developed a lucrative trash collection business, later expanding into street cleaning and contracting. Protégés of First Ward leader Amos Slack (1840-1899), the Vares used their political contacts to collect over $18 million from fifty-eight city contracts between 1888 and 1911.

The Vares invested their profits in building an unstoppable political machine in South Philadelphia, using their clout to win more contracts and earn more money. Their sway increased significantly when voters elected George to the State Legislature in 189o and to the State Senate five years later. When George died suddenly in 1908, Ed assumed his Senate seat. Bill rose from the Philadelphia Select Council to become U.S. congressman for Philadelphia’s First District, which encompassed his home district of South Philadelphia. In the years before World War I, Vare-controlled men headed most of the important City Council committees, including Finance, Highways, and Street Cleaning.

In theory, the McNichol and Vare blocs agreed to divide the city at Market Street to ensure peace within the “contractor combine.” In practice, the two camps waged a bloody struggle for control of the Republican City Committee, composed of the party leaders of the city’s forty-eight political wards. The upper hand in the ongoing battle was held by Boies Penrose (1860-1921), who represented Pennsylvania’s corporate interests in the U.S. Senate for twenty-five years. While Penrose usually favored McNichol, he borrowed significant sums from the Vares, paying them back by arranging private contracts with major corporations.

The deaths of McNichol, Penrose, and Edwin Vare between 1917 and 1922 left William S. Vare as the undisputed boss of Philadelphia. During the 1920s, he commanded more political power than any other single Philadelphian before or since. A Senate investigation in 1926 concluded that thanks to Vare’s army of election “watchers,” the average Philadelphia voter had a one-in-eight chance of having his ballot recorded accurately on Election Day. One commentator compared Vare to the Italian Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini (1883-1945), with the distinction that the citizens of Rome enjoyed clean water, clean streets, and efficient transportation, unlike the citizens of Philadelphia.

Lavish Public Works Program

When Vare’s protégé, Receiver of Taxes W. Freeland Kendrick (1874-1953), took office as mayor in 1924, he launched a lavish program of public works, reversing the austerity measures of his predecessor J. Hampton Moore (1864-1950). Ground was broken for the Broad Street Subway, expanding the city’s mass transit system beyond the Market-Frankford line. Work stepped up on the Delaware River Bridge, the Free Library, and the Museum of Art, projects that had languished under Moore. The city allocated funds to rebuild Philadelphia General Hospital, to construct a new hospital complex at Byberry, and to erect a City Hall Annex. Millions of dollars were devoted to a Sesquicentennial International Exposition to mark the country’s 150th anniversary in 1926, a dismal failure that attracted half the visitors of the 1876 Centennial.

William Vare benefited directly and indirectly from much of this largesse. The Vare Construction Company received eleven major contracts totaling more than $1.4 million during the Kendrick administration, including work on the Broad Street Subway, the Museum of Art, and the Municipal Stadium. Vare used his influence to have the Sesquicentennial Exposition relocated from Center City to South Philadelphia, effectively bankrupting the fair but ensuring that his constituents would receive millions of dollars’ worth of jobs and infrastructural improvements.

In 1926, William S. Vare ran as the Republican candidate for the United States Senate from Pennsylvania, winning by a significant margin. Alarmed by Vare’s reputation as a corrupt urban boss and his plans to modify Prohibition by permitting the sale of beer and wine, the U.S. Senate refused to seat him until it had investigated the conduct and financing of his campaign. Under the stress of the Senate inquiry, in August 1928 Vare suffered a massive stroke that left him partially paralyzed. After deliberating for more than three years, the Senate voted in December 1929 to deny Vare his seat. Although Vare remained the nominal head of the Republican Organization in Philadelphia until shortly before his death in 1934, his political dominance effectively ended with the Senate rejection.

The Great Depression, with its devastating impact on jobs, municipal expenditures, and construction, marked the end of the golden age of the contractor boss. As the Depression abated, a new generation of influential contractors emerged in Philadelphia, but none dominated the political landscape as had McNichol or the Vares. Many of the later contractor bosses were Democratic and Irish Catholic, reflecting the city’s changing demographics: John B. Kelly Sr. (1889–1960), Matthew H. McCloskey (1893–1973), and John McShain (1896–1989).

While the era of the contractor kings had passed, Philadelphia remained in many ways their creation. The expansionist legacy of the contractor bosses remained manifest in such physical landmarks as City Hall, Roosevelt Boulevard, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Market-Frankford Subway-Elevated Line, and Benjamin Franklin Bridge. This durable infrastructure served as a testament to a body of men who bent the political will of a major American city to accommodate their own personal and professional interests.

Thomas H. Keels is a local historian and the author or coauthor of six books on Philadelphia, including Forgotten Philadelphia: Lost Architecture of the Quaker City (Temple University Press, 2007). His latest work, Sesqui! Greed, Graft, and the Forgotten World’s Fair of 1926, a study of the ill-fated Sesquicentennial International Exposition, will be published by Temple in early 2017. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Edwin H. Vare (Pennsylvania State Senate)

- William Scott Vare (Biographical Directory of the United States Congress)

- Cleaning Up in Philadelphia (PhillyHistory Blog)

- Lincoln Steffens, Excerpts from "Philadelphia: Corrupt and Contented" (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- 1861-1945: Era of Industrial Ascendancy (Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission)

- Political Machine (Encyclopedia Britannica)