West Chester, Pennsylvania

By Anne E. Krulikowski | County Seat

Essay

Boosted by its strategic location some twenty-five miles from Philadelphia, West Chester, Pennsylvania, grew and prospered for most of its history as the county seat of Chester County. Pressured by mid-twentieth-century suburbanization, the borough lost its commercial and residential dominance and even its role as county seat somewhat diminished as the growth of the surrounding county required more employees and offices than the borough could reasonably accommodate. In the early twenty-first century, the borough established itself as a destination for restaurants, entertainment, and specialty shopping that attracted residents and visitors alike.

The Borough of West Chester originated from a crossroads in West Goshen Township, Chester County, the county originally adjacent to Philadelphia to the west. The modern town developed on land that was part of several contiguous land grants from William Penn (1644-1718). About 1710, Goshen Road to the small settlement at Goshen in East Goshen Township and then to Philadelphia was the first road laid out. An east-west road (Gay Street, eventually West Chester Pike) through these tracts to Philadelphia was laid out in 1735. Ten years later, a north-south road (High Street) to Wilmington, Delaware, also opened. A log tavern built near the crossroads was named Turk’s Head Inn and marked by a large sign of a turbaned Turkish man, so local farmers described where they lived as “Near the sign of the Turk’s Head.” A log schoolhouse built at the intersection of these two roads served as a hospital for casualties from the Battle of the Brandywine, which took place a few miles to the south in 1777.

The definitive event that propelled this crossroads toward town status was the Pennsylvania legislature’s decision in 1786 to move the county seat of Chester County from Chester, in the southeastern part of the county, to the more centrally located Turk’s Head, to accommodate larger numbers of residents in the northern and western portions of the county. After opposition from Chester, in 1789 the legislature split off the eastern part of the county to form Delaware County and Turk’s Head became West Chester, county seat of a smaller Chester County. Ten years later, the state legislature accorded it borough status, freeing residents from township control and enabling officials to collect taxes and provide services, such as constables, to residents. Its role as county seat determined the character of the early town: law offices, taverns and hotels, livery stables, banks, small shops, and dwellings quickly clustered near the county courthouse (completed in 1786) and nearby prison.

Athens on High Street

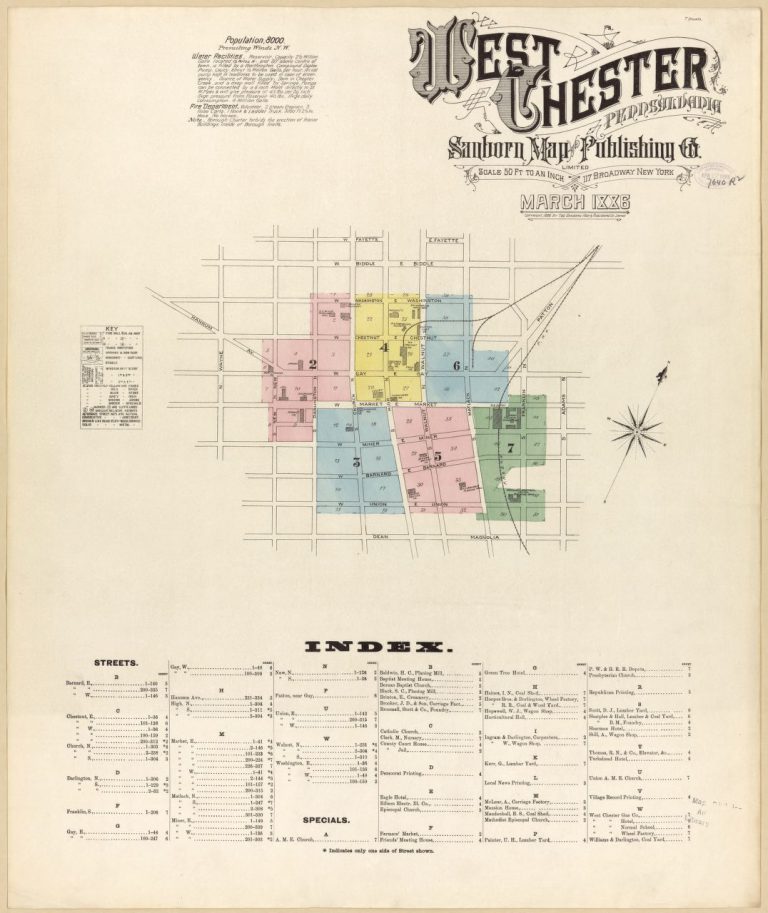

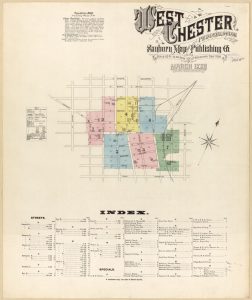

The county seat experienced steady growth in the decades prior to the Civil War. The population jumped from 374 residents in 1790 to 4,757 in 1860. Early residents were British, mainly English, with a small group of Irish Roman Catholics present. A Roman Catholic Church was the first built in the borough, where it was located to serve a large area of the county. Many Protestant denominations eventually followed, but the Society of Friends built the second church in 1812, and Quakers were long prominent among residents and community leaders. The 1820s through the 1840s were perhaps the most significant decades in the borough’s history, with its greatest population growth and a building boom that shaped the physical layout and appearance of the town. Spanning out from the courthouse at the center, the borough developed in four quadrants defined by the meeting of the two main roads (Gay and High Streets), a pattern that continued into the twenty-first century.

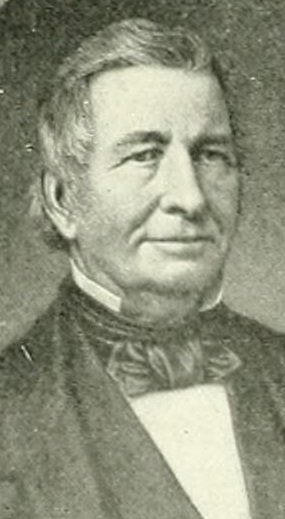

Improved transit quickened development by connecting the borough with surrounding counties. In the mid-1790s, the state opened a road extending from Gay Street west to Strasburg in Lancaster County. The creation of several more state roads through the vicinity, one extending from New Hope in Bucks County to Cecil County, Maryland, prompted entrepreneur William Everhart (1785-1868) to develop an area just south of the court house. New roads and the growth of the surrounding population encouraged other investors to purchase and subdivide centrally located farms in the borough, which consisted of 1.8 square miles.

Wagon roads often proved problematic, but the advent of the West Chester Railroad in 1832 promised more efficient ties to Philadelphia via nearby Malvern. Sensing new opportunities, Everhart erected the first purpose-built office building, the Everhart Building (ca. 1833) on Market Street across from the courthouse. Connections to a larger world benefited county farmers and diversified the borough’s economy to include artisan crafts such as pottery, clock- and watchmaking, and a few small early steam-driven industries, such as an iron foundry and a brewery. Nurseries also became a significant part of the industrial economy of West Chester as they organized production and marketing to buy, sell, and trade species throughout the world. The most successful—Morris Nursery (1849), Kift Nursery (1852), and Hoopes Brothers and Thomas (1856)—were founded by midcentury, although they experienced their peak years later. In the 1890s, Hoopes Brothers employed three hundred county workers and sold about 900,000 seedlings annually. The business lasted until 1948.

By the Civil War, Black residents accounted for about 10 percent of the population. African Americans had been present from the borough’s earliest days, including a few slaves. In the early nineteenth century, some experienced economic success. The 1838 tax list, for instance, included sixteen Black artisans and small businessmen as taxpayers, including a blacksmith, barber, shoemaker, oysterman, and huckster among several other occupations. A few Black residents lived scattered around the borough, but by the 1850s most lived in the southeast quadrant, near brick- and lumberyards, the West Chester Gas facility (1852-1960s), and by the Civil War a second rail line, in a neighborhood known as the East End. While small row- and semi-detached houses set close to the street characterized portions of all quadrants, in the East End they were largely unrelieved by larger dwellings and spacious yards, reflecting the lower economic status of most East End residents.

Courthouse as Anchor

Even as the town diversified, the courthouse remained the vital center of the county seat. Steady county settlement boosted courthouse business and supported a growing number of law offices, banks, taverns, livery stables, dwellings, and churches for visitors and residents. In 1846 Philadelphia architect Thomas U. Walter (1804-87), who had previously designed the Bank of Chester County (1836) in the Greek Revival style, was commissioned to design a new and larger courthouse in the same style as county affairs outgrew the 1786 courthouse. These centrally located buildings and others in popular architectural styles marked the transition of the simple market town to a more cosmopolitan society.

The county seat offered opportunities to able and ambitious lawyers, businessmen, and physicians who also served as representatives to the state legislature and the United States Congress and as judges on district courts in Philadelphia. These men and their families moved back and forth between West Chester, Philadelphia, Harrisburg, and Washington, D.C., so that this small urban center was as up-to-date as larger cities and a model for other towns in the county, as its fashionable churches and public buildings by architects such as Walter and William Strickland(1788-1854) visually demonstrated.

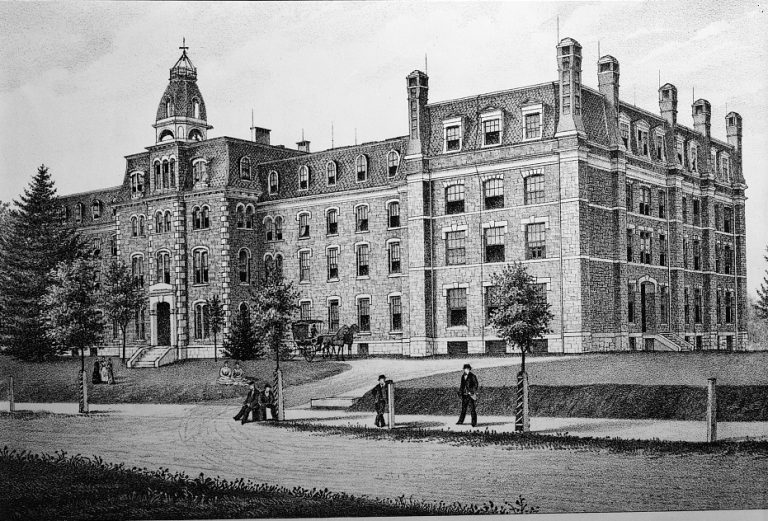

After county and borough administration, education was the most enduring economic activity. The cosmopolitan and well-educated lawyers, judges, doctors, and Quaker farmers desired superior education for their sons and daughters. The many private academies and boarding schools for young men and ladies drew students from Philadelphia and farther afield. The West Chester Academy (est. 1813) was the antecedent of West Chester University, while the Institution for Young Gentlemen run by Antoine Bolmar (1797-1861) attracted many students from the South and from the West Indies, particularly Cuba.

Civic leaders also founded an array of scientific and cultural institutions. In 1848, a new Horticultural Hall became the cultural center of the county during an era in which lectures by famous people constituted entertainment: Horace Greeley (1811-72), Sojourner Truth (c. 1797-1883), and Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-82) were some of the luminaries of the day on the speakers’ circuit who lectured there. Four years later, this building became the site of the First Women’s Rights Convention in Pennsylvania and the second in the nation after the 1848 women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York. The combination of schools, cultural institutions, and Greek Revival architecture earned West Chester its nicknames as the “Athens of Pennsylvania” and “Athens on High Street.” The well-educated population supported three newspapers, one of which, the Chester County Times, housed in the Everhart Building, published the first biography of Abraham Lincoln, helping him win the presidency in 1860.

A Suburb of Philadelphia

Following the Civil War, West Chester grew steadily for another lengthy period through World War II, although the Depression presented challenges to the town’s general prosperity. Even during the national recession of the 1870s, the decision of the state legislature to transform the West Chester Academy into a state Normal School provided a significant catalyst for growth.

Increasing responsibilities of county administration led to construction of a courthouse annex in 1891. The following year, the founding of the Chester County Hospital, originally sited within the borough but in the 1920s relocated a few hundred yards outside the boundary, increased the importance of the county seat to area residents. Further notable additions to the architectural landscape, including the borough’s first and only skyscraper for the next one hundred years and the six-story Farmers and Mechanics Trust Building (1906), showcased West Chester’s prosperity.

By the time West Chester celebrated its centennial in 1899, its residents no longer thought of it as an isolated inland town but as the most important suburb of Philadelphia, according to the Centennial Souvenir. Just the year before, the trolley line along West Chester Pike that traveled between Sixty-Third Street in Philadelphia and Newtown Square was extended to West Chester. Additionally, just prior to the Civil War, a second rail line had connected the borough to Philadelphia through Media, Delaware County, and also with Baltimore and the South, readying the borough for more industrial development. After the Civil War, the sections of the two eastern quadrants closest to the rail lines became the most industrialized in town, as the massive Hoopes Brothers and Darlington Wheel Works (1866-1973) joined established manufacturing concerns. The most important company for a time was the Sharples Separator Works, established in 1881 by P. M. Sharples (1857-1944). This company’s most profitable product was a centrifugal cream separator sold internationally, inspired by the prevalence of dairy farming in the county. At its height, the works employed six hundred borough and county residents, but it went out of business in the 1930s Depression.

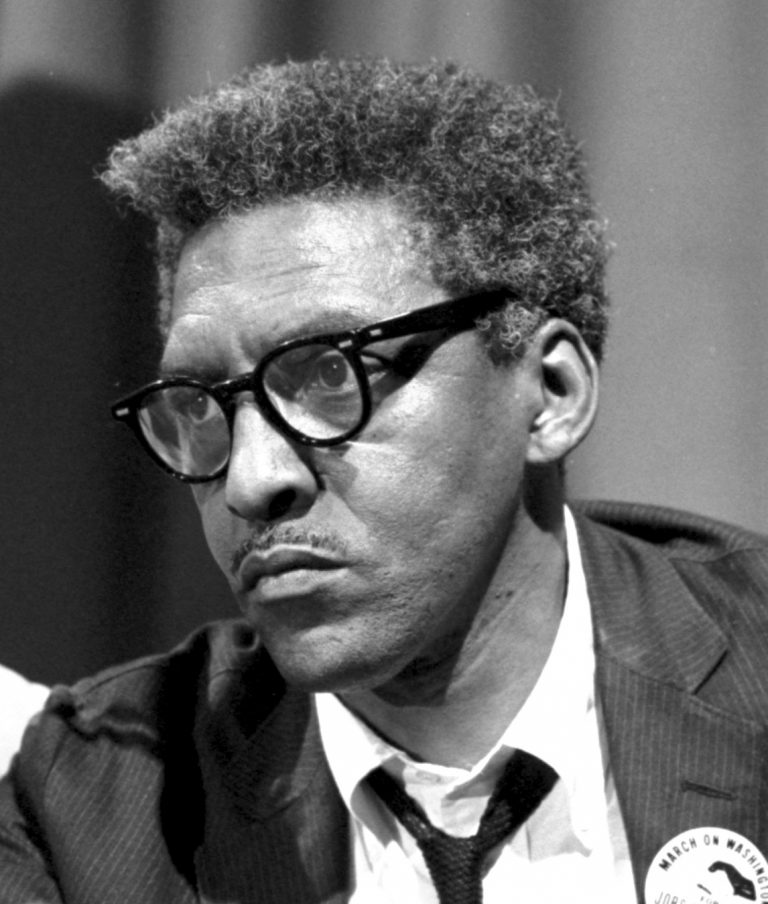

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, banks clustered around the courthouse remained important for visitors to the county seat and county farmers who sold their produce in two market houses in the borough. Hotels, taverns, and restaurants remained necessary in a county seat, and some well-known establishments were owned by Black residents. One of these was the Spence Restaurant on Gay Street, known for the area’s best oyster stew and patronized by white businessmen. On the other hand, the Magnolia House Hotel, owned from 1866 to 1897 by the son of a southern slave, was located in the largely segregated East End and catered exclusively to Black customers, including Frederick Douglass (c. 1818-95). In the early twentieth century, civil rights leader Bayard Rustin (1912-87) grew up partly in the East End, though the relatively wealthy grandparents who raised him lived at several different locations within the borough, including the white Catholic section. He attended the segregated Gay Street School and West Chester Junior High, although biographers state that because of many interracial activities, Rustin did not realize as a boy that the schools were segregated. As a student at an integrated high school with few Black students, Rustin was arrested for trying to sit in the white section of the Warner Movie Theater.

World War II propelled a second major industry related to county agriculture. West Chester-born chemist G. Raymond Rettew (1903-73) worked on improving the county’s mushroom production and in the process successfully developed a way to mass-produce penicillin. By 1943, Chester County Mushroom Laboratories in West Chester produced most of the world’s supply. The expanding mushroom industry further diversified the population by attracting Hispanic residents to the county and to the borough. Wyeth Pharmaceuticals took over production during the World War II and produced penicillin in the borough during the post-war antibiotics boom. Wyeth operated a West Chester plant until the early twenty-first century.

Decline and Renewal

With the end of World War II West Chester seemed poised for another era of steady growth. Instead, the changing landscape of retail and the fast-paced suburbanization of the surrounding rural county contributed to the loss of businesses and, in the 1970s, a loss of some 10 percent of the population in the borough. Within the borough, as in many larger cities, successful revitalization efforts focused on downtown.

In the 1950s, West Chester remained the retail center of Chester County, with three department stores and fifteen smaller clothing and shoe stores. These stores lost business, however, after King of Prussia Plaza, about twenty miles northeast of West Chester, opened in the early 1960s. The borough’s history as a crossroads destination was reversed when a new four-lane highway (Route 202) built from Wilmington, Delaware, to King of Prussia bypassed the borough and made the journey from West Chester to King of Prussia a twenty-minute drive. The last remaining department store in town, Mosteller’s, declined through the 1970s and closed in 1981.

West Chester’s population reached its peak in 1970, even as the population of the surrounding county exploded as farmland rapidly converted to suburban tracts, a process accelerated by the transformation of West Chester Pike (Route 3) into a four-lane highway in the 1950s. The accompanying expansion of county government led to tension over whether the small county seat could accommodate additional offices and parking spaces. In the 1960s, a new wing was added to the courthouse, and a few years later the Dague Building was constructed to house the county library and other offices. For a while branch libraries proved sufficient to serve the county, but in 1980 the main county library moved from West Chester to the site of the new Exton Square Mall (opened in 1973), where it was more easily accessible by automobile.

The increasing importance of the automobile at the expense of public transportation hurt the borough. West Chester was connected by frequent bus service to the Sixty-Ninth Street Terminal in Upper Darby via West Chester Pike. However, in 1986, rail service from the county seat to Media and from there to Philadelphia was discontinued, partly because county officials preferred to expand service at the Exton Station on SEPTA’s Paoli-Thorndale line where there was room for parking. By the end of the twentieth century, Exton, eight miles north of West Chester, rather than the county seat, in large measure became the retail, entertainment, and transportation hub of southeastern Chester County.

The disposition of government services also affected the borough. In 1993, the location of a new Chester County Government Services Center outside the borough in Westtown removed five hundred county workers from the downtown district. Within a short time a number of small businesses in West Chester closed. The movement of services out of West Chester finally reversed in 2008, when the Chester County Justice Center replaced the Dague Building, bringing some county workers back to the borough. Further proposals for such controversially large-scale buildings (including downtown apartment buildings and hotels) and additional high-rise parking, however, generated concerns that such investments would compromise the quality of life in the borough.

Over time West Chester also became a university town, benefiting businesses but creating unwanted development pressures at the same time. By 2016, the university enrolled almost seventeen thousand students drawn mainly from Chester and surrounding counties, many of whom lived in the borough during the school year. As customers and employees of many downtown restaurants, bars, and boutiques they helped boost the town’s commercial viability. On the other hand, traffic congestion, lack of adequate parking facilities, unruly late night behavior, and the university’s desire to further expand its enrollment and physical facilities caused concern for many borough leaders and residents. A 2002 borough planning study found that the “extremely” high percentage of housing units devoted to rental housing created a destabilizing effect on neighborhoods, a trend that began in the 1980s and continued in the early twenty-first century.

Many sections of the borough contained spacious dwellings, yards, and green spaces, but residential neighborhoods varied greatly and some areas remained segregated. The East End remained home to most African American residents (about 12 percent of the population), although that quadrant was no longer heavily industrial and student rental housing was pressing eastward from the university campus. The western side of the northwest quadrant was home to most of the borough’s Hispanic residents (about 13 percent of the population). In 2000, many families living in those areas accounted for a large part of the 20 percent of residents living below the poverty line.

The revitalized downtown, though, presented a different story. Together, the borough and the Business Improvement District, a partnership of downtown commercial interests formed in 2000, promoted West Chester as an entertainment and cultural heritage destination. By the second decade of the twenty-first century, small boutiques, a farmers’ market, restaurants, and music festivals increased foot traffic and generated nightlife, and by 2016 the borough population had slightly surpassed its 1970 peak. Proposals for several more luxury hotels, high-rise apartment buildings, and a live performance theater demonstrated that, despite ongoing tension between development and preservation, West Chester had resuscitated its reputation as a cosmopolitan place to visit and live.

Anne Krulikowski holds a Ph.D. in American History with a concentration in material culture/preservation from the University of Delaware. She teaches American history and public history at West Chester University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Borough of West Chester

- West Chester University

- Downtown West Chester Business Improvement District

- Greater West Chester Chamber of Commerce

- Daily Local News

- Proceedings of the Women's Rights Convention, 1852 (Library of Congress)

- Chester County Courthouse (Philadelphia Architects and Buildings)

- Hoopes Brothers & Darlington Photographs (Hagley Digital Archives)

- Sharples Digital Collection (West Chester University)

- West Chester University Historic Photographs (West Chester University)