Philadelphia Campaign

Essay

During the War for Independence, in 1777, the British moved to seize Philadelphia in a series of battles that contributed to a turning point in the war. While the Philadelphia campaign strained British resources and exposed serious leadership issues with General Sir William Howe (1729-1814), the effectiveness of American forces led by General George Washington (1732-99) helped to bring France into the war as an American ally.

The summer of 1777 saw the British deeply entrenched in New York City with plans to seize Philadelphia, the revolutionary capital, and destroy Washington’s army. In a stalemate in New Jersey with Washington’s forces, Howe received approval to begin a campaign against Philadelphia as long as his forces remained available to assist an invasion from Canada of General John Burgoyne (1722-92).

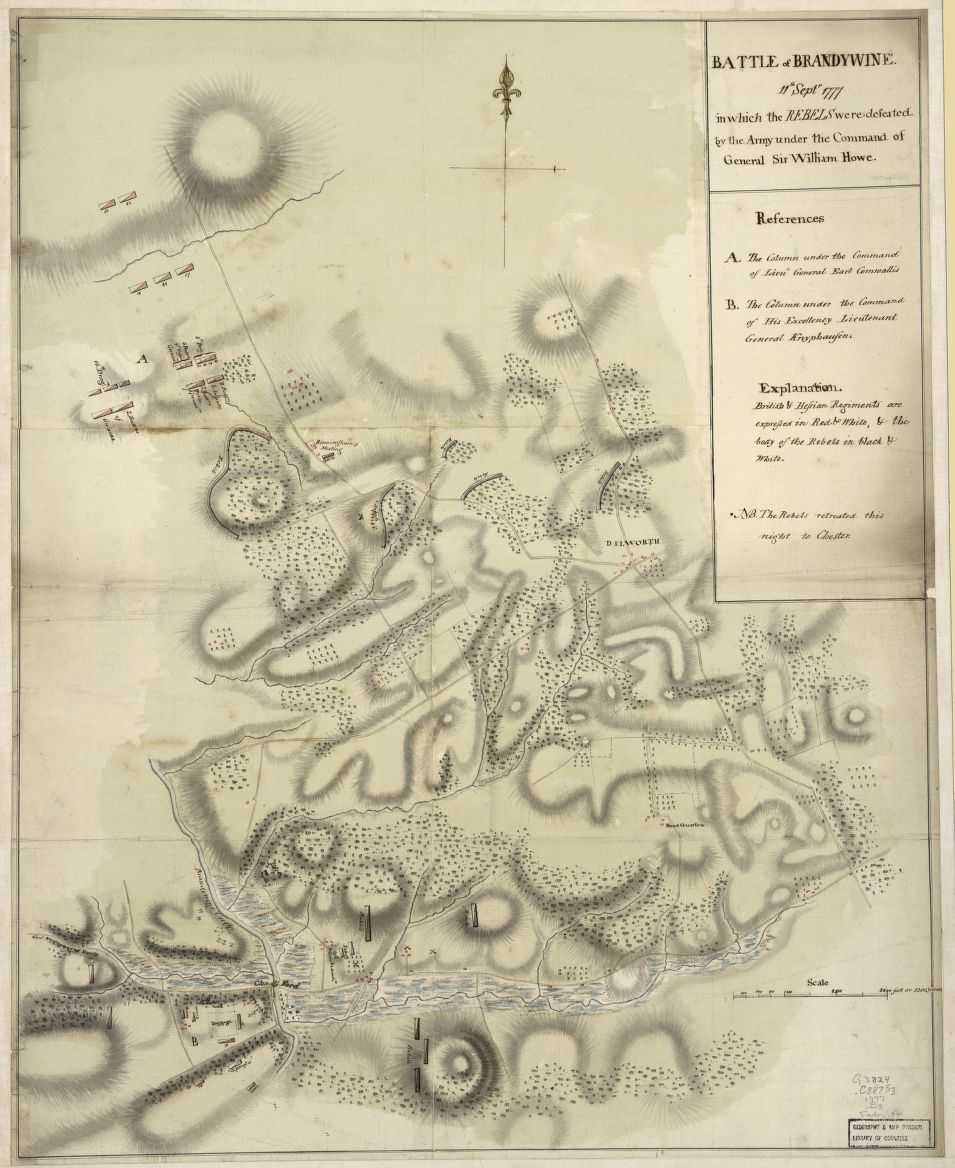

After receiving permission for his campaign against Philadelphia, in August 1777 Howe sailed up the Chesapeake Bay with a force of 13,000 troops, disembarking at the Head of Elk, Maryland. As Howe began his march to Philadelphia, Washington scrambled to respond. On September 11, 1777, British forces engaged with the Americans at the Brandywine River, an engagement that saw strategic reconnaissance errors by the Americans. Washington hoped to force an attack on the high ground of Chadd’s Ford but a heavy fog provided protection for the British as they moved to outflank the Americans. With Washington’s right flank completely exposed, the American troops could do little more than fight for time as they retreated to Chester.

Washington, alarmed at Howe’s pace, sent the division of Brigadier General “Mad” Anthony Wayne (1745-96) to harass the British as they continued toward Philadelphia. Wayne set up camp in Paoli close to the British, who learned of Wayne’s presence and attacked on the night of September 20, 1777. Wayne’s men, caught completely by surprise, saw the loss of 53 men and 71 prisoners taken. The battle was considered a complete disaster with Wayne facing charges of misconduct. Outraged at the charges, Wayne demanded a full court martial and investigation. The investigation determined that while Wayne had made tactical mistakes, he had not engaged in misconduct. The battle became a rallying cry for American soldiers who labeled the event the “Paoli massacre.”

Continental Congress Flees

Howe’s men continued toward Philadelphia as the Continental Congress abandoned the city and evacuated to Lancaster and then York, Pennsylvania. The British entered Philadelphia unopposed on September 26. Those with American sympathies had departed the city, leaving a relatively small group of Loyalists and those who were too poor to move. The British immediately set about identifying housing for troops and officers though space remained limited and plundering by British soldiers did not endear them to Philadelphia residents.

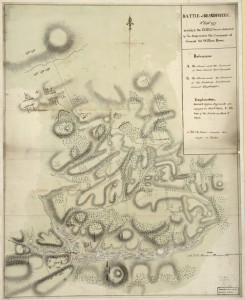

Howe positioned troops in both Philadelphia and the outlying community of Germantown. Washington, seeing a divided force and hoping to retake the capital, attacked the British at Germantown on October 4, 1777. Washington launched a complicated four-pronged attack but a heavy fog complicated communication. Cliveden, home to the prominent lawyer Benjamin Chew (1722-1810), became the site of intense fighting as entrenched British troops fired heavily upon the advancing American army. Ultimately, confusion and a lack of organization contributed to Washington’s defeat. Nevertheless, the bold attack impressed European observers who began to believe a disciplined army could pose a serious threat to the crown. The American army continued to improve and demonstrate its proficiency on the battlefield. In addition, the dramatic American victory at Saratoga, New York, in October 1777 suggested the patriots could win the war. Howe’s inability or refusal to support Burgoyne’s troops at Saratoga further compromised the crown’s ability to subdue the colonies and encouraged the French to ally with the American cause.

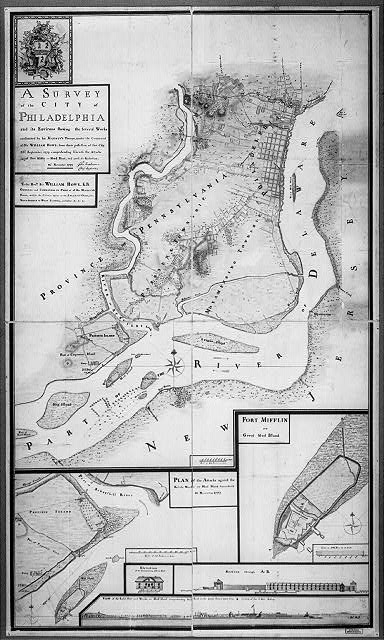

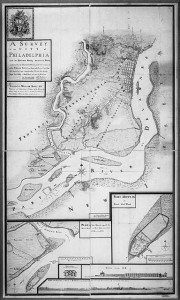

As Howe settled into Philadelphia he faced the pressing problem of supplying his troops. Food was scarce and provisions, limited. Washington’s army largely prevented the British from seeking supplies outside the city and the main point of entry into the city–the Delaware River–remained closed through strategic fortifications constructed the previous spring. Fort Billingsport, Fort Mercer, and Fort Mifflin buttressed the Philadelphia and New Jersey sides of the river. A complicated system of weighted spears known as “chevaux de frise” lined the bottom of the river, ready to pierce the hulls of unsuspecting British ships approaching the city. The fort system and chevaux successfully kept Howe from receiving supplies and, with winter looming, Howe recognized action needed to be taken.

Assault on Fort Mercer

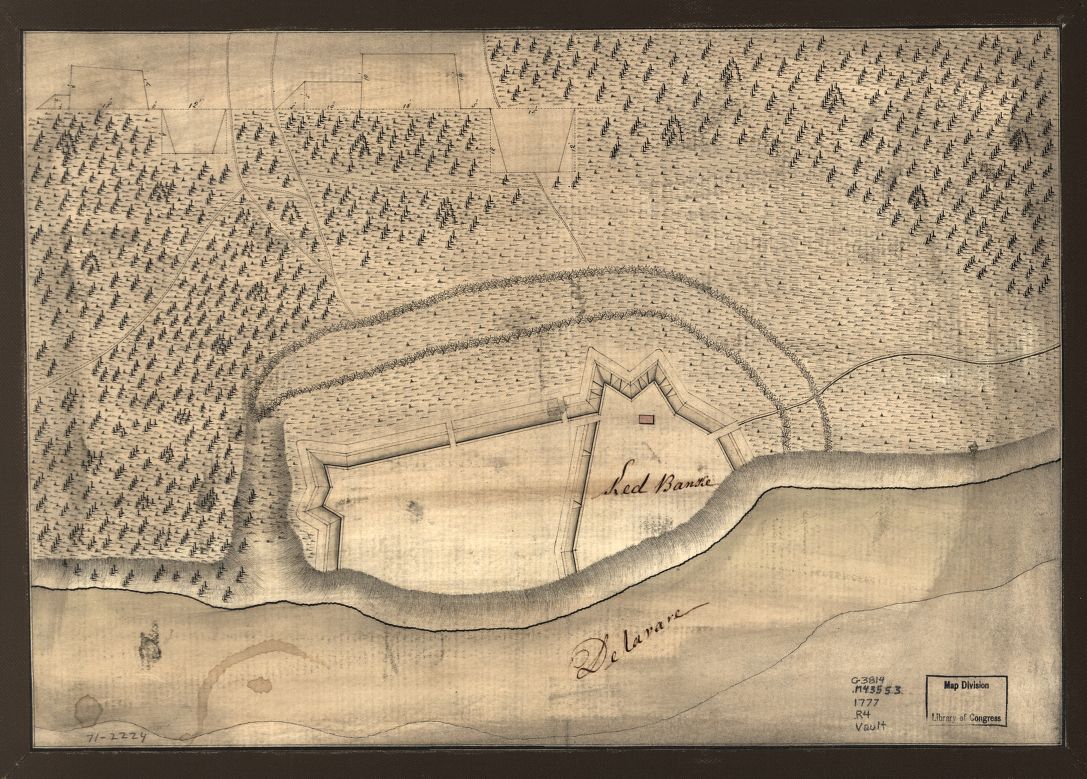

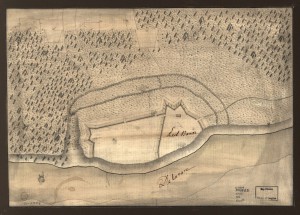

In late October, Howe turned his attention to Fort Mercer, located at Red Bank on the New Jersey side of the Delaware. Situated on a high bluff overlooking the river, Mercer provided a strategic defensive location opposite Fort Mifflin on Mud Island, south of Philadelphia. On October 22, 1777, Hessian forces under the leadership of Colonel Carl von Donop (1732-77) left Haddonfield, New Jersey, with orders to take Fort Mercer. Von Donop, defeated at Trenton by Washington’s forces, eagerly seized the opportunity to avenge his name. He commanded a Hessian force of approximately 1,200 men who arrived at Red Bank late in the afternoon. Mercer’s high walls as well as a series of sharpened logs known as abatis made the fort extremely difficult to scale. Complicating the Hessian assault was the arrival of the Pennsylvania Navy under the leadership of John Hazelwood (1726-1800), who began a series of barrages from the river. Unable to scale the walls and without artillery pieces to breach the fort, many Hessians died and were buried in a mass grave near the fort. The following day either by British design or as the result of enemy fire, the British ships Augusta and Merlin took fire and exploded, an event so loud it was heard miles away.

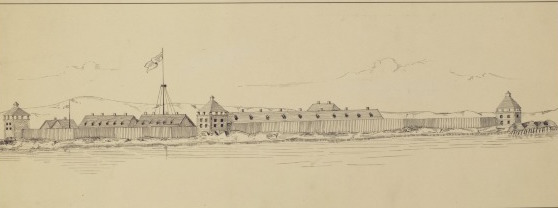

Failing to take Mercer, the British turned their attention to Fort Mifflin, which had been constructed in 1771 under the direction of British officer and engineer Captain John Montresor (1736-99) who, ironically, was now charged with destroying the fort. Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Smith (1752-1839) of the Maryland militia commanded the fort with a force of 200 men. Fort Mifflin saw the heaviest bombardment of the Revolutionary War. Beginning November 10, British forces shelled Mifflin by land and by water, inflicting heavy casualties. By November 15, the fort had been virtually destroyed with few men left to defend it. The Americans evacuated the fort and headed across the river to Fort Mercer. Within days of Mifflin’s fall, the Americans abandoned Fort Mercer, restoring British access to the river.

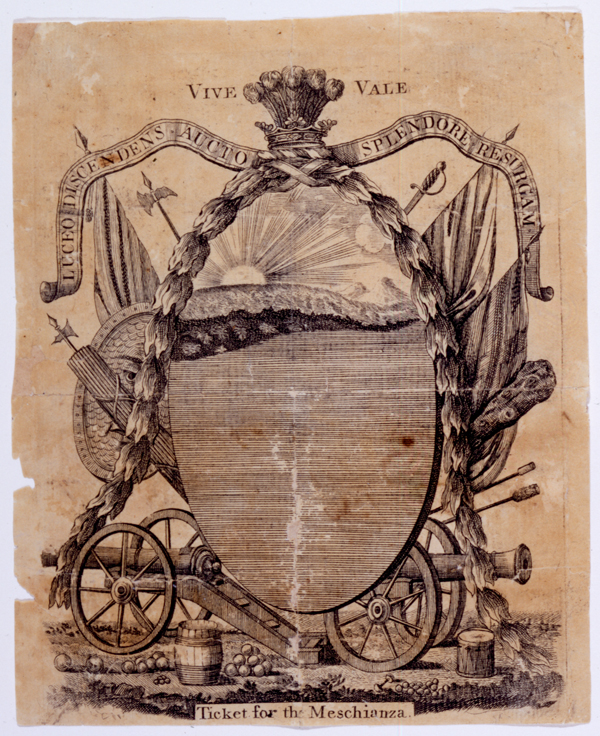

The river cleared, Howe’s troops finally received necessary provisions and settled in for winter. With the British now deeply established in Philadelphia, Washington’s forces set up camp for the long winter at Valley Forge. In October 1777, however, Howe had submitted his resignation, complaining he had not received the support he needed to effectively perform his position. The British relieved Howe of his duty in the spring of 1778 and replaced him with General Sir Henry Clinton (1730-95). Howe’s exit from Philadelphia is remembered for the elaborate party known as the “Meschianza,” which included over 400 guests, a 17-gun salute by British warships, and fireworks.

Along with the American victory at Saratoga, the Philadelphia campaign convinced France that the Americans were worthy allies. After the French entered the war on the side of the Americans in February 1778, the British abandoned Philadelphia in June and returned to New York for fear of an imminent French attack. Howe’s missteps in the campaign exposed the weakness in British military leadership and allowed Washington’s troops time to rest, train, and reorganize.

Jennifer Lawrence Janofsky, Ph.D., is the Giordano Fellow in Public History at Rowan University and curator of the Whitall House at Red Bank Battlefield.

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- The Philadelphia Campaign (ExplorePAHistory.org)

- Fort Mifflin Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.org)

- Battle of Germantown Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.org)

- General Sir William Howe Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.org)

- Gen. Anthony Wayne Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.org)

- Village of Valley Forge Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.org)

- Index of the Philadelphia Campaign (USHistory.org)