Orchard Window (The)

Essay

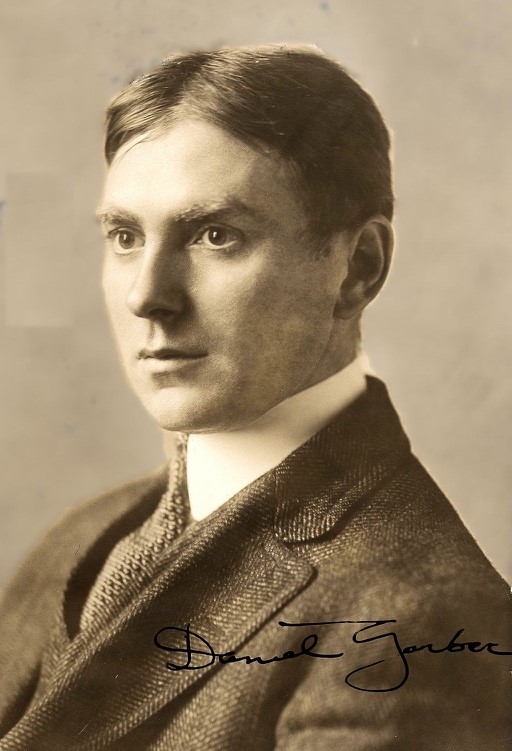

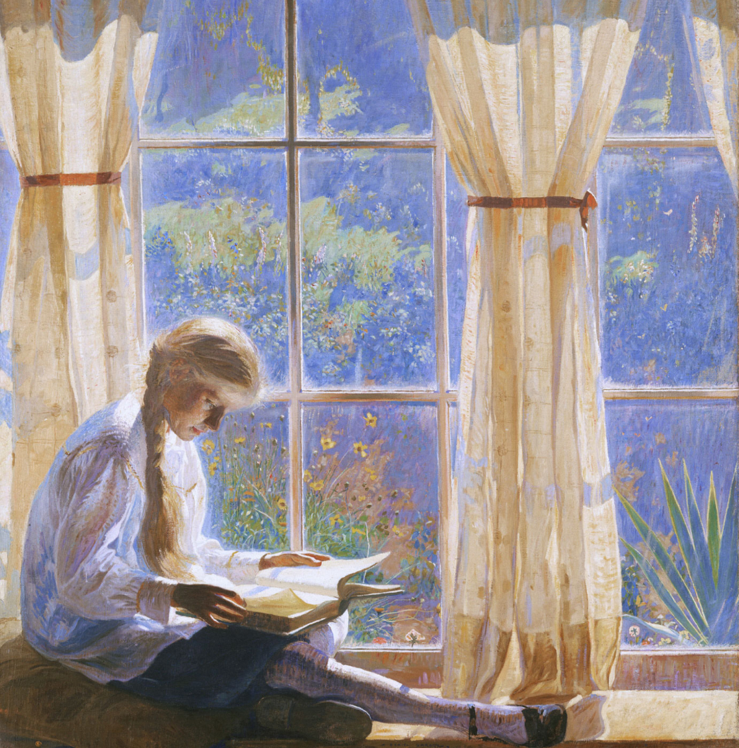

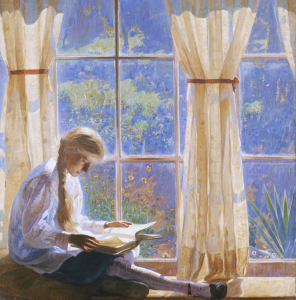

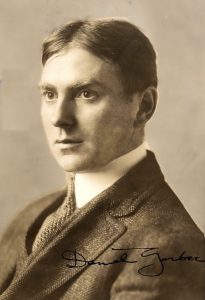

Painted in 1918 by Philadelphia artist Daniel Garber (1880-1958), The Orchard Window depicts the interior of Garber’s studio in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, and features his 12-year-old daughter Tanis sitting in a sun-dappled window seat, reading a book. This large oil painting on canvas has been highly regarded as a prime example of Pennsylvania Impressionism, a variation on the French Impressionism of Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Camille Pissarro (1830-1903).

The Orchard Window is one of Garber’s masterpieces, dating from a period when the artist reached the height of his popularity. In this painting, Garber combined the atmospheric concerns of impressionism with the sharp, careful drawing typical of all graduates of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. By flattening out the picture plane in the background (in other words, by making the view out the window almost two-dimensional), he also added a decorative quality that was new to his work at the time.

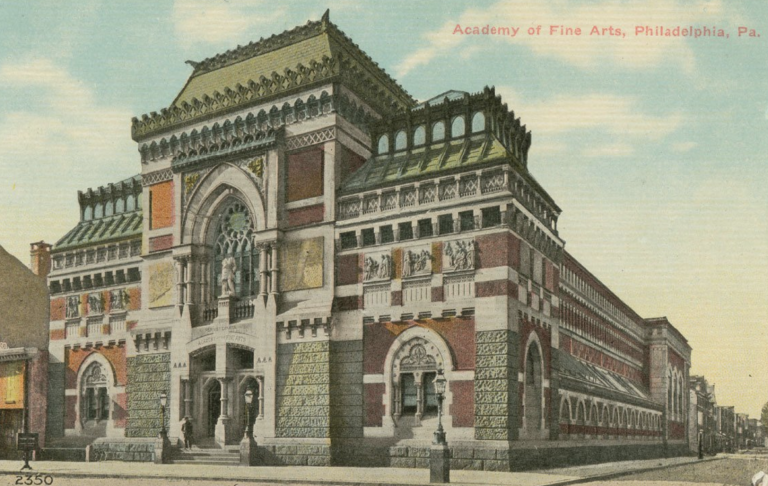

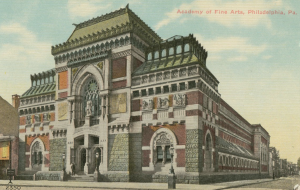

Born and raised in Indiana, after a brief period of study at the Art Academy of Cincinnati Garber moved to Philadelphia and enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. There, and at the Darby School of Art, a summer school in nearby Darby and Fort Washington, Pennsylvania, he received training from artists such as Thomas Anshutz (1851-1912) and Hugh Breckenridge (1870-1937). In 1905, he won the academy’s coveted Cresson Scholarship, which enabled him to travel and study in Europe for two years. In Europe, he encountered French Impressionism, which inspired him to become one of America’s leading artists working in the impressionist mode.

Garber returned to the United States in 1907 and settled with his wife, Mary, in Lumberville, a village just north of New Hope, Pennsylvania. He became a longtime leader, along with Edward Redfield (1869-1965), of the artist colony that sprang up in the New Hope area in the first quarter of the twentieth century. Garber’s studio at Cuttalossa Farm served as the setting for many paintings of his daughter Tanis, with whom he was very close. He loved the sunlight that came in through his studio window and the flower garden that stood just behind his studio. He took a great deal of pride in, and solace from, his home in the country, as can be seen vividly in The Orchard Window.

Garber for many years also had a home on Green Street in Philadelphia, where he lived during the academic year until about 1926. He began a long and successful career as a teacher, first at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women (later Moore College of Art and Design), and then at the Pennsylvania Academy. The critical and public responses to The Orchard Window illustrate the changing tides of Garber’s critical fortunes over the next century. The oil won the Temple Gold Medal for best painting at the 1919 annual exhibition of the Pennsylvania Academy, and magazine and newspaper reviewers immediately touted the work as very “American.” According to Gardner Teall (1876-1956), writing in 1921, “it reveals the spirit of American art, a thing one sees and feels, but which perhaps, is not so easy to define.” By 1930, however, critics were questioning whether it was possible to speak of any country as having a unique, instantly identifiable style of oil painting. Garber’s representational art gradually fell out of favor during the second and third quarters of the century, with the rise of abstract art.

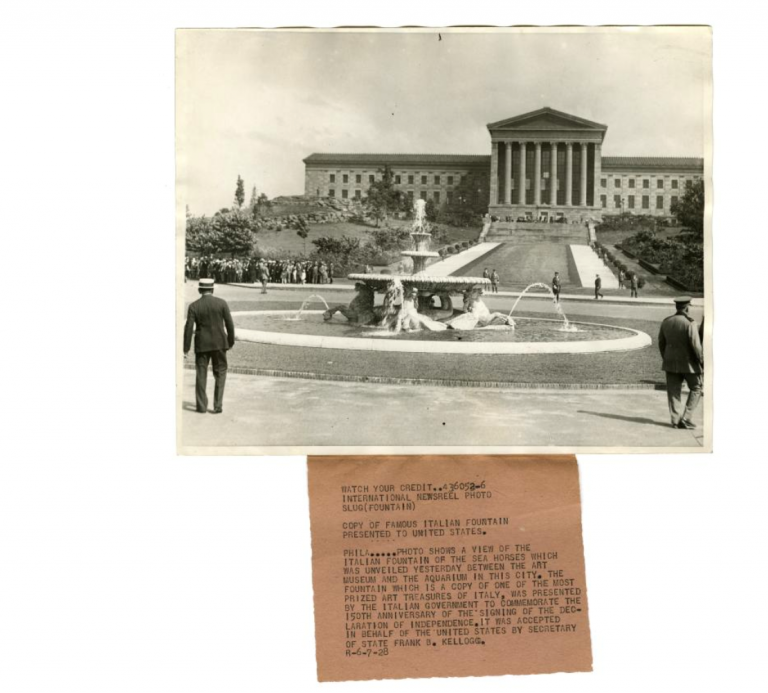

Garber’s work had almost been forgotten by 1976, when the Philadelphia Museum of Art included The Orchard Window in its Bicentennial exhibition of American art. The public, however, responded very enthusiastically to The Orchard Window at that exhibition, which in part motivated a 1980 Garber retrospective at the Pennsylvania Academy. This exhibition marked the centennial of the artist’s birth (as well as the 175th anniversary of the founding of the academy). More exhibitions of Garber’s works followed, several books and catalogues appeared, and his works earned higher and higher prices at auction. The reestablishment of his reputation, and that of his fellow New Hope School painters Edward Redfield (1869-1965) and Walter Schofield (1867-1944), drew in part from the nationalism surrounding the Bicentennial as well as from the realization, in many circles, that representational art was just as valid and important as nonrepresentational art. The work of Andrew Wyeth (1917-2009), for instance, and that of his fellow Brandywine School artists, became perceived as serious creative art by critics who had once panned it as “mere” illustration.

By the early twenty-first century, art historians regarded Garber as one of the Philadelphia area’s most important contributors to the history of American art. The Orchard Window became so popular that it appeared on jigsaw puzzles, coffee cups, placemats, and even advertisements for the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

In 1918, The Orchard Window represented a moment of calm to viewers who were wrestling with World War I and many other serious issues, among them racial tension and the beginnings of a flu pandemic that would kill at least 675,000 Americans. The painting continued to function in that manner in later years, bringing respite to viewers feeling unsettled by the pace of twentieth- and twentieth-first century life.

Mark Sullivan, Ph.D., is Associate Professor of Art History at Villanova University. His recent publications include Picturing Thoreau: Henry David Thoreau in American Visual Culture (Lexington Books, 2015), and two essays for The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia: “The Red Rose Girls” and “Pennsylvania Impressionism.” (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University