Trenton, New Jersey

By Evelyn Gonzalez | County Seat

Essay

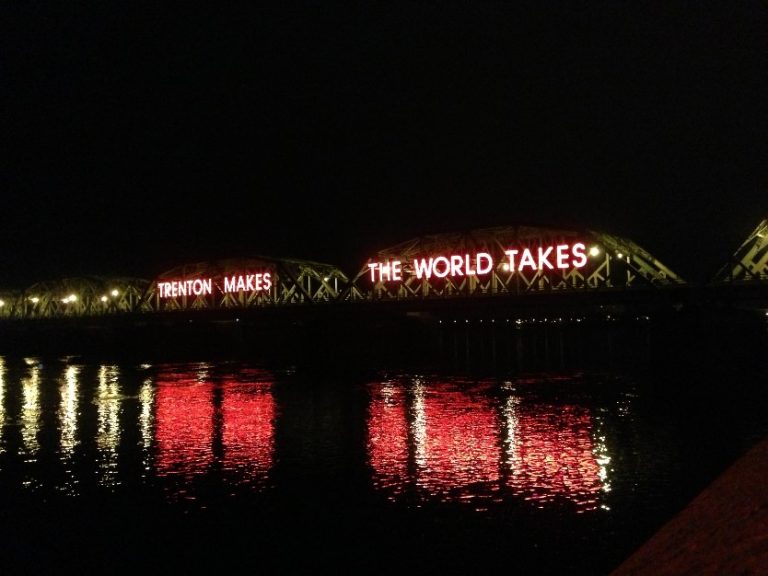

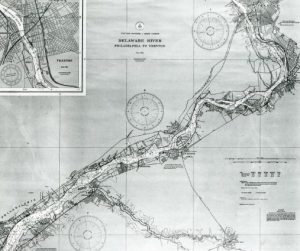

The state capital of New Jersey and the seat of Mercer County, Trenton parlayed its strategic location on the Delaware River into becoming one of the most productive industrial sites in the Greater Philadelphia region. A small city of only 7.65 square miles located halfway between Philadelphia and New York, Trenton conveyed its considerable status to the world through the sign the city erected in 1917: “Trenton Makes, the World Takes.” However, the loss of industry and the rise of social costs as the population shifted put the city into serious decline after World War II, challenges it faced into the twenty-first century.

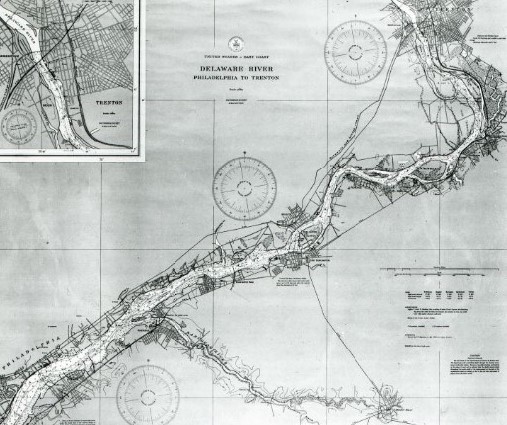

Europeans chose to settle in the Trenton area because it was the easiest spot to cross the Delaware. The area’s earliest inhabitants, the Lenape Indians, had already carved out an Indian trail connecting the Hudson and Delaware Rivers. During the colonial period that trail became the most direct route between Philadelphia and New York and as a roadway spurred Trenton’s growth into a town, a small industrial city, and later into part of a larger industrial corridor that stretched along the Delaware River through New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware.

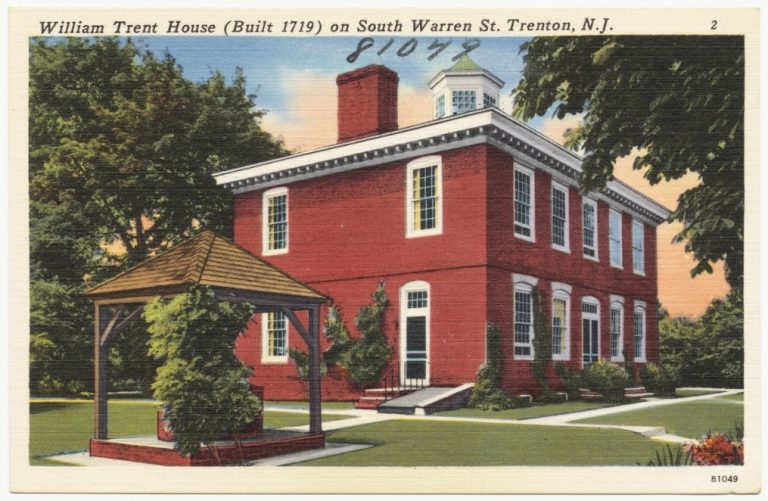

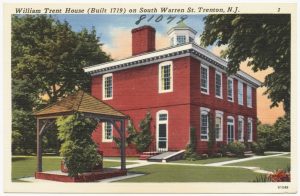

The Trenton area was first settled by English Quakers in 1679, when Mahlon Stacy (1638-1704) built a house and grist mill along the Delaware River. In 1714, William Trent (circa. 1653-1724), a wealthy Philadelphia merchant, bought Stacy’s property, laid out house lots for sale, and by 1719 “Trent’s Town” was the site of the county courthouse. By 1726, ferries crossed the Delaware to Philadelphia, and by the 1750s, stagecoaches reached New York. From then on, Trenton had a steady stream of travelers from Philadelphia and New York.

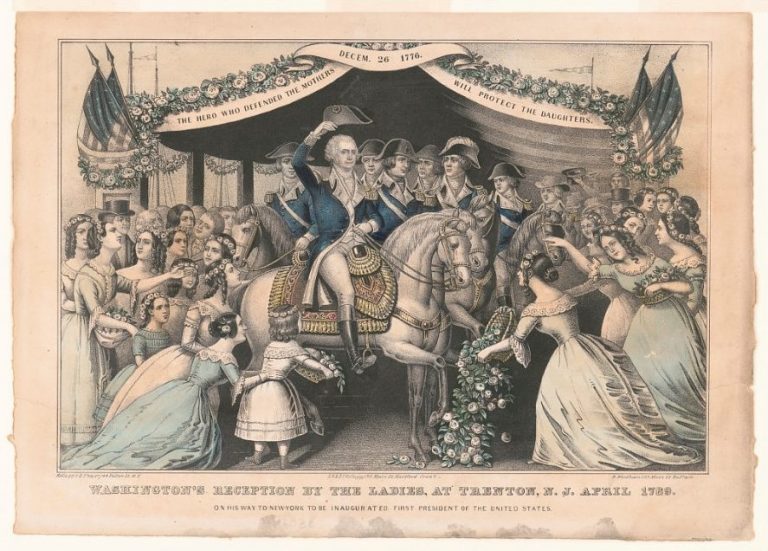

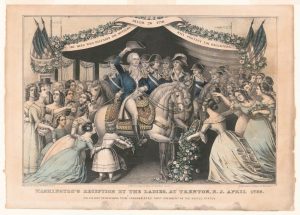

By the 1770s, Trenton had become the mercantile center of an area that sprawled over two counties. During the Revolution, it was the site of the two Battles of Trenton when the army of General George Washington (1732-99) crossed the Delaware and twice defeated the Hessian troops on December 26, 1776, and a week later on January 2, 1777. After the Revolution, Trenton became the state capital in 1790, an incorporated city in 1792, and a link in the new nation’s direct inland route from New England to the southern states. During the 1830s, bridges, canals, and railroads improved the Philadelphia-New York route. Transit reinforced Trenton’s central position in the area and led to the creation of Mercer County in 1838 with Trenton as the county seat.

Textiles, Steel, Rubber, Pottery

Good transportation links attracted new industries to Trenton from the 1840s on. Its first industry had been textiles. But in 1845, New York businessman Peter Cooper (1791-1883) opened an iron mill in Trenton, and later John A. Roebling (1806-1869), of later Brooklyn Bridge fame, moved his wire rope/steel cable business to Trenton as well. Many more industries followed. Two of the biggest were rubber, from the 1850s until the 1950s, and pottery (fine china and sanitary ware), from the 1860s into the twentieth century. By 1900, Trenton was a booming industrial city and part of a manufacturing belt along the Delaware River. Trenton had begun by selling manufactured goods to Philadelphia and New York, but it later sold high quality goods to the nation and the world. In 1917, the city proudly proclaimed its industrial might with a large electric sign on the Lower Trenton Bridge, saying “Trenton Makes, the World Takes.”

Trenton’s population grew and diversified with its industry. People from home and abroad flocked to Trenton’s mills and factories, causing the population to rise from 6,461 in 1850 to its peak of 128,009 in 1950. At that time, Trenton had the fifth-highest density of cities over 100,000 population, or around 17,000 persons per square mile. Its population also changed as thousands of immigrants toiled in Trenton workplaces, from the earlier Irish, German, and British, to the later Italian, Polish, Hungarian, and Czechoslovak. From 1905 on, the proportion of foreign born declined steadily, but a new stream of African Americans began arriving during World War I.

In the 1920s, Trenton still had a vibrant downtown, a rising population, and industries producing for the world. But by then, decades of mechanization had eliminated many jobs and weakened Trenton’s unions, and many Trenton companies had left the city. This process began in 1904 when U.S. Steel acquired Trenton Iron Works and continued when Colorado Fuel & Iron bought Roebling’s in 1953. These factors were obscured during World War I and the 1920s but were exposed by the 1930s Depression. The city only managed to survive with New Deal relief efforts and public works until World War II temporarily restored business and jobs.

Trenton’s prosperity ended in the post-war years. Manufacturing disappeared, while young families left Trenton for new housing and jobs outside the city. Downtown retailers relocated to suburban shopping centers, and cultural, state, and educational institutions also left. Only Thomas Edison State College and a satellite campus of Mercer County Community College remained downtown. In 1957, even the governor’s residence moved to Princeton.

African American Migration

Many African Americans migrated to Trenton for World War II defense jobs, and their numbers continued to grow afterwards. Although they constituted only 11 percent of the city’s population in 1950, racial tensions increased because they were arriving just when jobs were disappearing. This was revealed by the 1948 case of “The Trenton Six,” which drew international attention when six Black men were wrongly convicted for murdering a white storekeeper. Although they were later exonerated, racial distrust flared again when the city’s urban renewal program resulted in the demolition of homes of African Americans despite their protests. Tensions intensified in December 1967 when Black and white students clashed in Trenton Central High School, and again in April 9, 1968, the day of Reverend Martin Luther King Jr.’s funeral. Violence erupted after Black college student Harlan Joseph (1949-68) was fatally shot in the back by a white police officer. During later decades, Trenton suffered deeply from poverty, joblessness, and gang violence. Trenton remained well below the state’s poverty levels into the twenty-first century and often topped the list of the most violent cities of its size with consistently high murder rates.

While parts of the city declined, Trenton’s downtown and central core were rebuilt. This began in the late 1950s with John Fitch Way, an urban renewal highway that cut off the downtown from its Delaware River waterfront. It continued in the 1980s with new county and state office towers and the massive Hughes Justice Complex, and followed with entertainment and sports venues such as a new minor league baseball stadium for the Trenton Thunder in the 1990s. Renewal continued with conversion of the Roebling mills for housing and tourism and a new Trenton Transit Center serving Amtrak, New Jersey Transit, SEPTA, and the River Line. Trenton had a new skyline, but state buildings paid no city taxes, and state employees did not spend enough money downtown to assure revival. City officials often had misgivings about the state’s larger role. But without private investment, state initiatives were the only way to rebuild Trenton.

Trenton lost much population since the 1950s, dropping to 84,913 in 2010. Middle-class residents continued to leave, and African Americans increased from 23 percent of the population in 1960 to 52 percent in both 2000 and 2010. Hispanics began arriving in the 1960s, reaching 34 percent of the city’s total in 2010. Thereafter, the city’s population stabilized at over 84,000, while levels of poverty and crime declined, despite an isolated shootout at the Art All Night festival in June 2018. Earlier that year, multiple news outlets repeated a Wallet Hub online description of Trenton as “the worst capital city to live in.” Despite having to battle such negative publicity, the city was long inspired by the efforts of residents, civic organizations, and city officials deeply dedicated to Trenton and its future. In recent years, residents celebrated the 242nd anniversary of the Battle of Trenton and the city unveiled an ambitious master plan, Trenton 250. In September 2018, New Jersey’s new governor, Phil Murphy (b. 1957), pledged to revitalize the struggling city with new redevelopment and safety measures.

Evelyn Gonzalez is a Professor of History at William Paterson University of New Jersey. She has written essays for The Encyclopedia of New York City and The Encyclopedia of New Jersey and is the author of The Bronx (Columbia University Press, 2004). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University