Indentured Servitude

Essay

As in many parts of colonial North America, employers in and around Philadelphia recruited workers through indentured servitude, a system of bound labor that obligated individuals to serve for a term of years. Servitude began in the Delaware Valley with the seventeenth-century Swedish, Dutch, and English settlements, expanding after 1720 when a new wave of immigrants responded to the colonization of lands of the Lenapes and other Native people in Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey. While indentured servitude declined among whites by the late eighteenth century, term bondage gained new life into the nineteenth century when Pennsylvania and New Jersey gradual abolition acts bound Black children to serve the masters of their enslaved mothers. In addition, many of the enslavers throughout the region who agreed to emancipate Black people required them to labor additional years before becoming free.

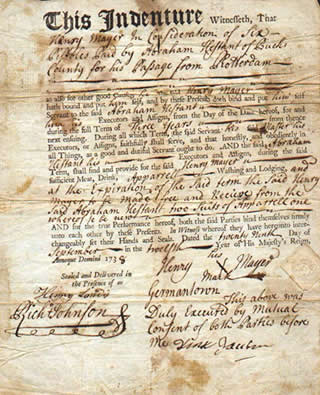

Indentured servitude encompassed a number of conditions that legally bound an individual, voluntarily or involuntarily, to serve a master for term of years. The contract could include a signed document, spoken agreement, or arise from a legislative act or judicial decision. Among the earliest New Sweden settlers were men who had been convicted of crimes in Sweden, then given the option of immigrating to the colony as bound servants. Peter Cock (1610-87), for example, worked as a cook and tobacco laborer before obtaining freedom, land, and an appointment as presiding justice of the Upland Court. Building on widespread use of servitude in the North American colonies and Caribbean, Dutch and English households employed servants in New Castle and the Whorekill in Delaware by 1671, and more arrived in subsequent years with plantation owners from the Chesapeake. Households brought Quaker and non-Quaker servants to West New Jersey after Salem founder John Fenwick (c. 1618-83) in 1675 offered transportation and freedom dues of clothing, tools, and one hundred acres in return for a term of four years. Servants also accompanied the Quakers who founded Burlington where, in 1682, Sarah Biddle (d. 1709) and other women persuaded the men’s meeting to require members to obtain permission before selling their servants’ terms of labor to non-Friends.

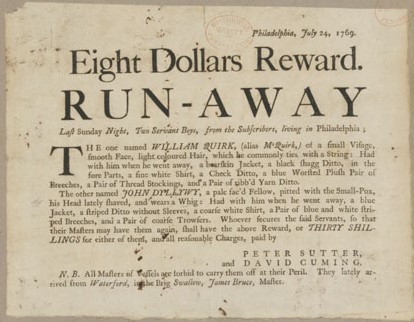

During the colonial period, many indentured servants who immigrated to the Philadelphia region received transatlantic transportation in return for laboring a term such as three, four, or five years. Upon arrival, the servant worked for a farmer, artisan, or shop owner who provided housing, food, and clothes and promised freedom dues at the end of the individual’s term. John Fenwick and William Penn (1644-1718) briefly offered land as incentives for servants to immigrate, though many failed to accumulate the capital to pay required fees and build farms. As demonstrated by newspaper advertisements for escaped servants, some men and women considered flight from onerous conditions worth the risk of punishment if caught.

Expanding Sources of Servants

While England remained an important source of servants in the eighteenth century, by the late 1720s growing numbers of Scots Irish, Irish, and German-speaking servants arrived in the Delaware Valley as part of larger immigrant flows. Spurred by a disastrous famine, more than five thousand people in 1729 landed in Philadelphia and New Castle from Ulster and southern Irish ports. Though fewer migrants arrived annually in subsequent years, many individuals and families took advantage of established routes in the transatlantic trade. Merchants welcomed the opportunity to transport servants along with customers who prepaid fares, thus making profits on the westward route and returning to Europe with flaxseed and other colonial products. Young single men composed a large proportion of the Scots Irish and southern Irish immigrants who obtained credit for their passage by agreeing to serve as indentured servants.

The flow of German-speaking immigrants grew from the late 1720s to peak in the early 1750s, as residents of the Rhine lands of southwestern Germany, Switzerland, and Alsace-Lorraine sought economic opportunity, lower taxes, and religious and political freedom in the Philadelphia region. Families and individuals who lacked sufficient capital for transportation turned to the redemptioner system in which, upon arrival, they agreed to fulfill a specific term of bound service according to their level of debt. German-speaking residents who had arrived earlier, sometimes relatives or friends, often facilitated the new immigrants’ settlement, including purchasing the time of teenage children. The teenagers thus helped to pave the family’s success by becoming redemptioners to resolve the family’s debt.

Growth of Wage Labor

Though Scots Irish, Irish, English, and German immigration resumed after disruption caused by the Revolutionary War, the share of European bound servants in the region’s workforce declined as wage labor increased. At the same time, the emancipation practices of individual enslavers and provisions of the gradual abolition acts passed by Pennsylvania in 1780 and New Jersey in 1804 forced thousands of African Americans into bound servitude. During the colonial era, some enslavers who manumitted Black persons required additional bondage prior to freedom. Enslavers expanded this practice after the Revolution, formalizing indentures through the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. Many masters from Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia sought to assuage guilt for holding people in perpetual enslavement while reaping profits by retaining them as bound servants or selling their indentures. The gradual abolition acts codified this practice for children born to enslaved women whom the laws failed to emancipate. In Pennsylvania, for example, children born after March 1, 1780, were obligated to serve their mothers’ enslavers until age 28; under the 1804 New Jersey law the ages were 25 for men and 21 for women. Like enslaved people and indentured servants, these children and young adults could be assigned long hours of plantation, craft, or domestic labor; punished with beatings; and sold at the enslaver’s whim. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court in 1826 somewhat limited the range of enslavement for a term by ruling that it would not extend to another generation. With no similar decision in New Jersey, the grandchildren as well as children of enslaved Black women remained subject to involuntary bondage until ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865.

Indentured servitude, including various forms of bound labor for a term, contributed in tandem with enslavement and wage labor to the economic growth of the Delaware Valley. Despite arduous conditions, many poor European immigrants gained economic opportunity by agreeing to serve in exchange for transportation. Some evaded death sentences by accepting deportation and servitude. With high mortality rates, many died before completing their terms. For enslaved Black persons and the descendants of enslaved mothers in the era of gradual abolition, enslavement for a term represented a long path to economic independence and political freedom.

Jean R. Soderlund is Professor of History Emeritus at Lehigh University. Her most recent books are Lenape Country: Delaware Valley Society before William Penn (2015) and Separate Paths: Lenapes and Colonists in West New Jersey (2022). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2024, Rutgers University.