Animal Protection

Essay

Moral doubt over the cruel usage of animals has a long history in Philadelphia. Public disapproval of such treatment surfaced by the late eighteenth century, but even with comprehensive laws designed to protect animals, and organizations devoted to enforcing those laws, the region has struggled to extend adequate protection to its nonhuman animals.

Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) once admitted that Philadelphians never found a better way to prevent hogs from trespassing than by blinding them, which was done by holding a red-hot knitting needle to their eyes. When encountering animals in early American history, it is far more common to uncover these stories of cruelty, rather than those of compassion. But during the eighteenth century, Philadelphia’s print culture and Quaker civic spirit made it particularly suited to begin advocating some forms of animal protection. Philadelphia had access to the transatlantic exchange of goods and ideas, and its residents were the heirs apparent to centuries’ worth of literature dedicated to the benevolent treatment of animals. Many of these European were available at the Library Company of Philadelphia for an annual membership fee of £10.

Due in large part to this literature, it became possible by the late eighteenth century to regard animals differently from the human-centered vision of earlier times. However, it was the American Revolution that transformed the treatment of animals into a moral issue deserving of attention from those who saw the Revolution as the first moment of their nation’s millennial destiny. It was in this context that many Americans attempted to reinvent their society to create a virtuous, Christianized national identity.

Animal Cruelty, Moral Sensibility

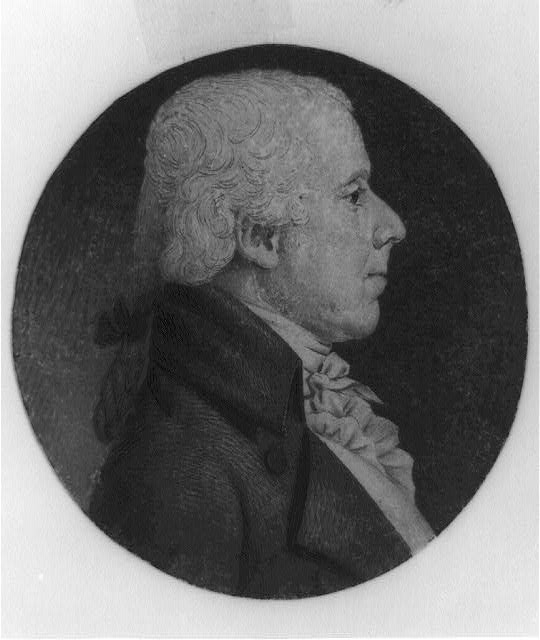

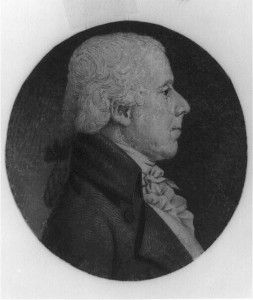

Philadelphia’s Benjamin Rush (1746-1813) was the dominant figure of this effort. Rush stressed the necessity of preparing the morals of American citizens by monitoring and correcting their behavior. Rush believed animal cruelty destroyed moral sensibility; he was so convinced of a connection between morals and humanity toward animals that he advocated laws to defend them from “outrage and oppression.”

Rush’s pleas were answered in 1788, when Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court rendered its decision in Republica v. Teischer. The defendant was accused of willfully and maliciously killing his horse. The court viewed this cruel act as destroying his moral sensibility and therefore making him unfit to be a virtuous citizen. The guilty verdict marked the first documented case of an American being convicted of animal cruelty.

This decision suggested a promising start for the institutionalized protection of animals, but it took an additional seventy-two years for the first legislation protecting animals to be passed into law in Pennsylvania in 1860. Seven years later, in 1867, Pennsylvania became the second state to charter a Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. New Jersey established its own SPCA in 1868, and Delaware followed suit in 1873. The passage of new legislation and the creation of these animal welfare groups reflected the values of a growing middle class that was self-consciously kind and caring to animals.

Municipal Campaigns

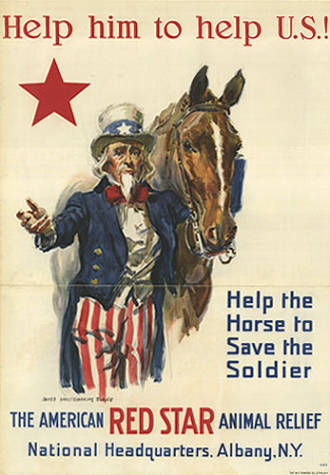

Around the turn of the twentieth century, Philadelphia’s city officials attempted to turn the city into a healthier environment. This led to increased efforts to control stray dogs and cats, who were believed to carry diseases such as rabies and poliomyelitis. The city funded killing sprees, during which dogs and cats were bludgeoned on the streets or taken to the Delaware River and summarily drowned. In 1911 alone, Philadelphia destroyed over 50,000 cats. These horrendous measures were met with resistance. The Women’s Branch of the PSPCA, based in Philadelphia, campaigned for kinder methods of control, and even built one of the nation’s first animal “shelters.”

By midcentury, the modern pet industry was in place. Although this entailed the unfortunate commodification of animal lives, it also led to the proliferation of specialized services such as medical care facilities and municipal-run shelters. The last three decades have seen a further rise in pet keeping and animal welfare groups. Yet the foundation for animal protection was laid down by historical, cultural, and legal precedents formulated during unique historical moments such as the post-Revolutionary reform movement and the reforms of the last half of the nineteenth century. Contemporary courtroom discussions often echo language from centuries ago. For instance, a bill currently pending in Pennsylvania seeking to make it a third degree felony to “willfully and maliciously” kill or harm an animal, mirrors the language used in the 1788 Teischer decision.

Organizations such as the PSPCA, NJSPCA, and DSPCA also have their roots in the late nineteenth century. Today, these animal welfare organizations are among the most active in the nation, providing care for animals who might otherwise never receive much needed attention. In addition to state-sponsored entities, numerous local, volunteer-based organizations have emerged in recent years. These organizations use social media to report cruelty, communicate about lost or abandoned animals, and circulate petitions. Grassroots organizations, capable of mobilizing public opinion and reaching an ever-increasing audience, create new potential for working with state-sponsored organizations to secure protection for animals in greater Philadelphia.

Bill Leon Smith is pursuing his PhD in Early American History at the College of William and Mary. He is also an Associate Fellow with the Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics. His research focuses on the development of animal ethics and other forms of humanitarianism during the eighteenth century. Prior to William and Mary, he served as a World History teacher at Burlington Township High School, in Burlington, New Jersey. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- The woman who set the tone for animal rights in Philadelphia (WHYY, March 26, 2014)

- Philadelphia Gun Club sues animal rights group, claiming stalking and intimidation (WHYY, April 11, 2014)

- From near extinction to internet sensation: the remarkable comeback of Pennsylvania’s bald eagles (WHYY, April 24, 2014)

- The implications and reality of elevating animal rights (WHYY, July 10, 2014)

- A million-dollar program to help control Philadelphia's cat population (WHYY, August 10, 2014)

- Of pigeons and pets: Pa. animal rights bill dies (WHYY, October 26, 2014)

- With new law protecting them from the cold, dogs have their day in Philly (WHYY, December 23, 2014)

- Stray cats in Philly get a helping hand with Chestnut Hill workshop (WHYY, March 23, 2015)

- With restored Delaware Bay stopover, threatened red knot population holding steady (WHYY, May 26, 2015)

- NJ lawmaker moves to increase penalties for stealing then selling pets (WHYY, August 31, 2015)

- Camden County mulls ban on sale of animals from puppy, kitten mills (WHYY, September 11, 2015)

- Del. animal welfare agency selects out-of-state contractor (WHYY, November 24, 2015)

- Lawmaker unleashing plan to crack down on New Jersey puppy mills (WHYY, January 4, 2016)

- New Jersey debates whether cat declawing is cruel (WHYY, March 31, 2017)