Armories

Essay

Armories served as military training and recruiting sites, arms depots, headquarters, and social clubs for the nation’s citizen-soldiers. Early armories in Philadelphia were simply rented spaces in commercial buildings. After the Civil War, permanent structures for the exclusive use of the Pennsylvania National Guard supplanted these ad hoc armories as business interests responded to labor unrest by funding an armory construction boom. In the twentieth century, government-funded armories evolved into community centers as well as military sites. Armory design reflected these changes in purpose, patronage, and function.

During the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Philadelphia and other cities lacked permanent armories. Militia units such as the First Troop, Philadelphia City Cavalry, the Second Troop of Light Horse, and the State Fencibles met in hotel rooms and taverns and drilled in public parks and squares, riding schools, and circuses. For drill, these units often rented floors in multistory commercial buildings, including the Union Building at Eighth and Chestnut Streets, the cast-iron Swain Building at 503-7 Chestnut Street, and a restaurant in the Northern Liberties neighborhood known as Military Hall. However, these facilities were not structurally strong enough to support drills by large units or secure enough to protect arms and equipment from theft.

In 1857, Philadelphia became one of the first cities to possess a permanent armory when the Infantry Corps, National Guards, purchased ground opposite Independence Hall and built the three-story National Guards Hall. In addition to quarters, storage, and meeting rooms, the building contained a drill hall on the second floor that could support an entire regiment.

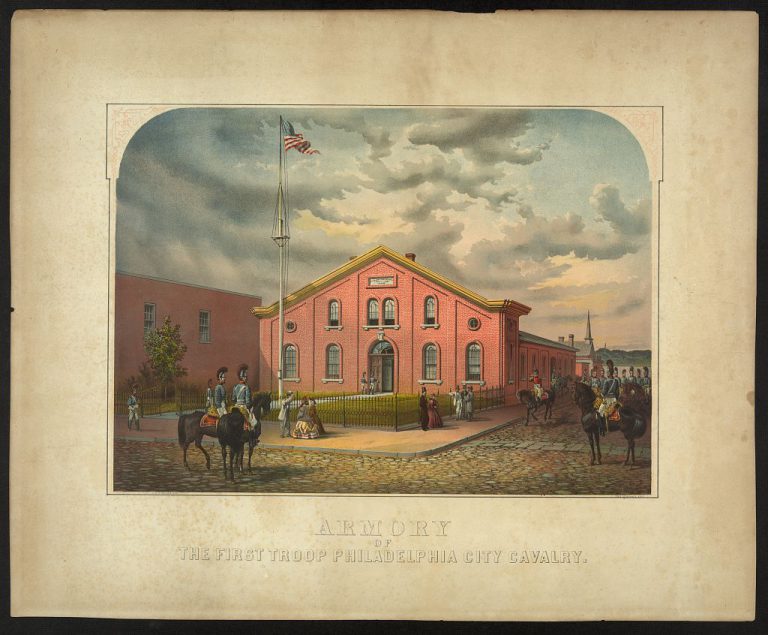

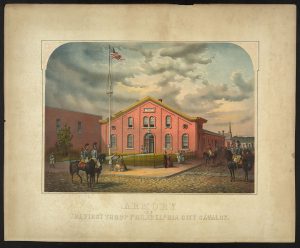

The First Troop constructed its first armory, a two-story structure, in 1863. In 1874, the troop commissioned the architectural firm Furness & Hewitt to design a new armory, to be built at Twenty-First and Ash Streets with funds bequeathed by wealthy members. Frank Furness (1839-1912) designed a compact three-story structure with a drill hall annex in the style of a medieval castle. According to historian Robert Fogelson, the building was one of the nation’s first castellated armories, which were distinctive for their thick walls topped with battlements, narrow windows, and bartizans. Industrialists and National Guard officials favored this style because it provided greater security for personnel and equipment in times of labor unrest. Architects embraced it because it unified form and function.

Armories Privately Funded

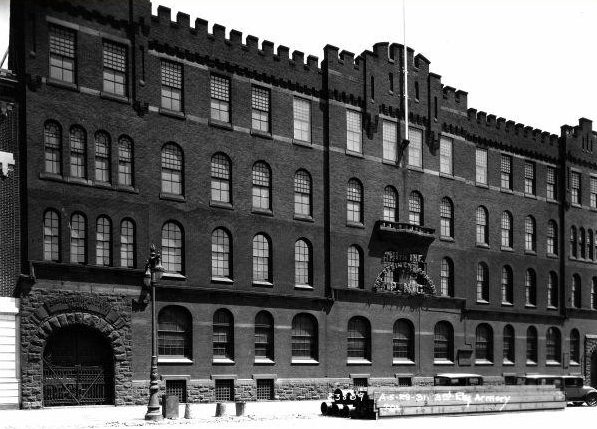

In an era of labor unrest, fundraising for armory construction in Philadelphia accelerated as wealthy private donors increasingly came to view the Pennsylvania National Guard as a strikebreaking force. In the wake of the nationwide Great Railroad Strike of 1877, Philadelphia gained new armories for the First Regiment, Second Regiment, and First Troop. James H. Windrim (1840-1919) designed the First Regiment Armory (built in 1884), located at Broad and Cherry Streets until it was demolished in 1979. The Second Regiment Armory (1895-97), designed by the firm Rankin & Kellogg, stood at Broad Street and Susquehanna Avenue. The First Troop’s third armory (1901), at Twenty-Third and Chestnut Streets, replaced the Furness armory, which suffered a collapsed roof in 1899 following a snowstorm. The local firm Newman, Woodman, & Harris designed the new armory, which continued to be used by the First Troop into the twenty-first century. All three castellated armories limited access to the interior with raised windows and single entranceways. As a cavalry armory, the First Troop Armory’s interior contained a spacious central hall with a dirt floor to serve as a riding ring (later paved to accommodate motor vehicles). These buildings received funding almost entirely from private donors. For example, the patrons of the First Regiment Armory included the Pennsylvania Railroad Corporation, merchant John Wanamaker (1838-1922), and Edwin Benson (1804-1909), an ex-National Guard officer and future president of the Union League.

By the end of the century, Philadelphia boasted six permanent armories. In New Jersey, meanwhile, officers of New Jersey’s Sixth Regiment successfully lobbied the state legislature to approve construction of a new armory in Camden to replace the old one at Bridge and West Streets (which remained standing until destroyed by fire in 1906). A Philadelphia contractor completed the new armory in 1897, and it remained in use as an armory, and after 1953 as a convention center, until its demolition in 1977 to create a site for a Veterans Administration hospital. For state officials and guardsmen, protecting the men and stores from attack by a mob was the primary purpose of the armory. Toward that end, architect Charles A. Gifford (1861-1937) designed the Camden Armory on Haddon Avenue to look like a fortress and a line of railroad track was laid alongside the structure to allow for the safe transport of troops out of the city. Gifford’s design for the Second Regiment Armory (1905), in Trenton, likewise retained many of the features of the castellated style. In the early twentieth century, Camden gained an additional armory on Wright Avenue to serve as the headquarters of a field artillery unit.

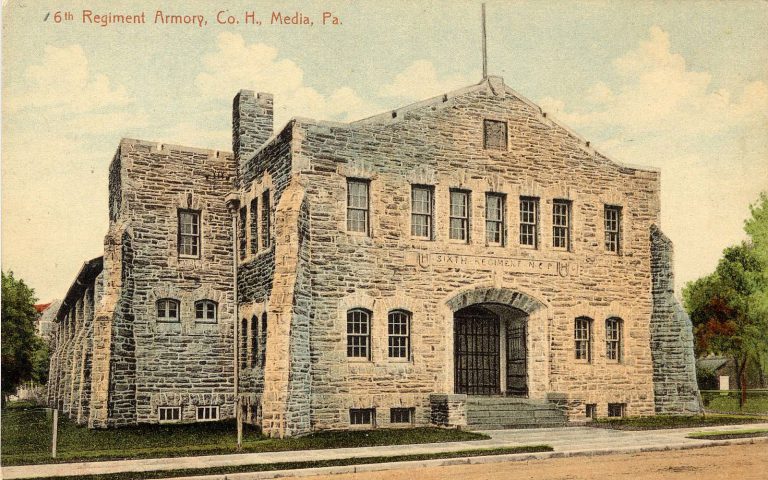

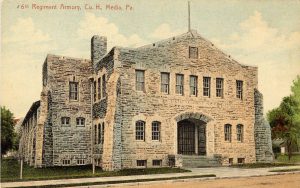

Unlike Pennsylvania, New Jersey built its armories mostly from public funds. The state legislature passed armory bills—five in the span of a decade—that authorized appropriations and established a state armory board that supervised the construction of new facilities. Pennsylvania followed suit when that state’s legislature created its armory board in 1905. The influx of this new source of funding led to a surge in construction in the Philadelphia suburbs, with armories sprouting in Media (1908), West Chester (1916), Reading City (1919), and Norristown (1928). Delaware also shifted from private to public funding of its armories. Troop B, First Delaware Cavalry, was able to raise money from private sources to build its home at the Wilmington Armory, located on Twelfth and Orange Streets. From 1890 to 1925, this “State Arsenal” served as quarters for all of the city’s National Guard units. When guardsmen complained that the space was too cramped, the Delaware legislature authorized a State Armory Commission to build a new armory and appropriated $250,000 for that purpose.

Military Use Gives Way to Civilian Use

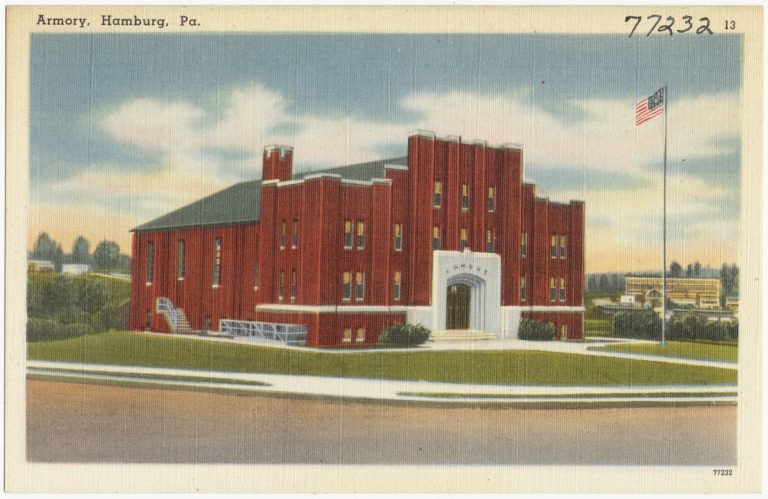

As the perceived threat of a revolution by labor subsided and the federal Militia Act of 1903 transformed state militias from industrial police forces to reserve forces for the regular Army, the purpose and form of armories underwent a marked change. With armories no longer considered targets of attack, federal, state, and city governments hired architects to design new armories with civilian functions in mind and adapted existing armories for public use. Armories in a diversity of architectural styles superseded the fortresses of the late nineteenth century. In Philadelphia, Windrim designed the Third Regiment Armory (1898), Broad and Wharton Streets, in the Romanesque style typical of the day but also included the features of a medieval castle, such as crenellations. The armory became the site for circuses, prizefights, and fraternal club meetings, and was converted into loft apartments in 2003. Philip H. Johnson (1868-1933) designed two armories in the Classical Revival style: a three-story cavalry armory (1916) resembling a railroad station at Thirty-Second and Lancaster, later adapted into a gymnasium by Drexel University, and the two-story General Thomas J. Stewart Memorial Armory (1928) in Norristown. Delaware architect Edward Canby May (1889-?) chose an Egyptian Revival style for his design of the Wilmington Armory (1928), located on Tenth and DuPont Streets. During the 1930s, the armory construction program of the Works Progress Administration and Public Works Administration continued this process toward civilian-oriented armory functions and design. To save taxpayer money, economy of design became the watchword, in stark contrast to the monumental privately-funded armories of the nineteenth century. Armories typically followed standardized designs with T-shaped or I-shaped plans in Art Deco or Art Moderne style. The New Deal dramatically increased the amount of federal funds disbursed by the states for armory construction. As a result, armories proliferated across the region, especially in towns and suburbs. Examples include the Hamburg Armory (1937) in Berks County and the Special Troops Armory in the Ogontz neighborhood (1938-39) of Philadelphia and company-sized armories in Milford (c. 1938) and New Castle (c. 1934-35?), Delaware.

At the turn of the twenty-first century, a few of these suburban and small town armories were turned over to local communities to use as they saw fit. For example, the Borough of Media donated the Media Armory to the Pennsylvania Veterans Museum and the West Chester Armory was converted into a theater for the performing arts.

National Guard armories in the region developed in tandem with architectural fashion, the mission of the citizen-soldier, and the role of government in the social life of the nation. The ornate castellated armories of Philadelphia, Camden, and Wilmington provide physical evidence of domestic turmoil and close links between the National Guard and their wealthy patrons during the post-Civil War era. Guardsmen’s reliance on private funding for armory construction not only helped turn state militias into a police force for industry, but also enabled local architects to develop a distinctive style for a building type that had never had one. The shift to public funding in the twentieth century armories meant that armories were often the product of pork barrel legislation or took the form of government make-work projects. States responded to the public desire for more civic spaces by expanding construction to small towns and suburban neighborhoods. Architects, in turn, embraced contemporary styles and the armories lost much of their aesthetic distinctiveness.

Jean-Pierre Beugoms is a Ph.D. candidate in History at Temple University. He is working on a dissertation about the logistics of the U.S. Army during the War of 1812. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers Univeristy

Gallery

Links

- Local Landmarks For Sale: National Guard Armories (Blog of the Pennsylvania Historic Preservation Office, June 26, 2013

- The Theater at The Armory in West Chester, PA (23 N. Digital, YouTube, June 16, 2014)

- Governor Signs Armory Over to City (Milford (Delaware) Live, June 28, 2017)

- Postcard Images of Camden, N.J. (dvrbs.com, Armory page)