Veterans and Veterans’ Organizations

Essay

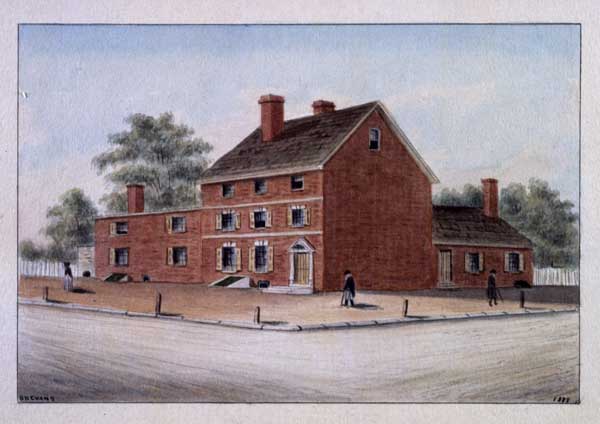

Military veterans began organizing in the Philadelphia area during the waning days of the Revolutionary War. As the Continental Army disbanded, its veterans often met at City Tavern and the first general meeting of America’s first veterans’ organization, the General Society of the Cincinnati, occurred there on May 4, 1784. Just as regularly, however, veterans congregated in the streets, engaging in acts that authorities viewed as mutinous. Philadelphia-area veterans emerged from this tumult to become integral to the region’s identity and prominent in the nation’s veteran affairs.

In the era of the American Revolution, Americans expected their veterans to follow the ideal of a citizen soldier embodied by the tradition of Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus (519 BCE-430 BCE), a consul in ancient Rome. When summoned, he set down his plow to command an army against invaders. Sixteen days later, Cincinnatus returned to his fields. He shunned all honors. Among veterans of the American Revolution, however, many who took up arms cared less about glory than they did about collecting their promised pay and bounties. This became evident in the streets of Philadelphia.

On October 4, 1779, more than a year after the British Army ended its 1777-78 occupation of Philadelphia, a large group of militia gathered at Burns Tavern on North Tenth Street. The disdain of the tradesmen who manned the city’s militia shifted from the British to Philadelphia’s merchants, whom they accused of profiteering while avoiding service.

March of Humiliation

The militia forcibly marched four prominent merchants through town in an attempt at public humiliation. It then stormed the house of James Wilson (1742-98), a prominent political ally of the merchants. This attack on “Fort Wilson,” ended by the arrival of the Philadelphia Light Horse, resulted in five dead and seventeen wounded. Authorities soon pardoned the several militia that they arrested to alleviate the heightened class tension in the city that their captivity had produced.

Continental Army veterans shared the financial concerns expressed by the militia. In January 1781, the 2,400 veterans of the Pennsylvania Line, disgruntled about their coerced reenlistment, lack of pay, and poor conditions, mutinied. Authorities responded quickly. Joseph Reed (1741-85), president of Pennsylvania’s Supreme Executive Council, met with representatives from the disgruntled Line at its camp in Princeton, New Jersey. He addressed their grievances by granting discharges to those who sought them and by offering more favorable terms to those who chose to reenlist.

Two years later, their war won against Great Britain, veterans unified once more. Rather than going home as ordered, units from York, Carlisle, Lancaster, and Maryland joined veterans in Philadelphia to demand their promised pay. Congress deemed this a mutiny and relocated to Princeton. The protest collapsed when veterans received word that an army under the command of General Robert Howe (1732-86) was marching toward the city under orders to quell the uprising. This incident ultimately resulted in the constitutional provision granting the U.S. Congress exclusive jurisdiction over the nation’s capital.

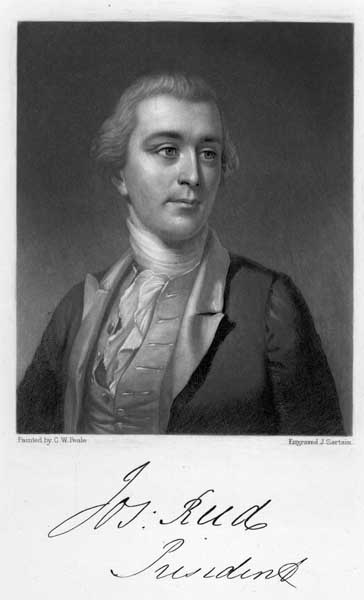

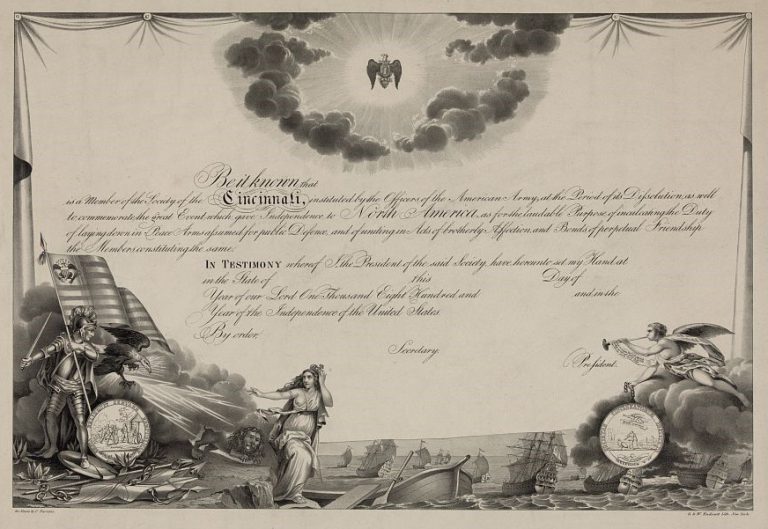

While the Continental Army’s soldiers took to Philadelphia’s streets, its officers retired to the city’s back rooms. They created the State Society of the Cincinnati of Pennsylvania on October 4, 1783, at the City Tavern, months before the General Society held its first meeting there. This rendered the Pennsylvania Society as the ninth of fourteen constituent societies to comprise the General Society of Cincinnati, an organization proposed by Major General Henry Knox (1750-1806) at the Continental Army’s encampment at Newburgh, New York, in May 1783. The society’s founding document, the Institution, acknowledged the subordination of the military to civilian rule. It created a fraternal organization for former officers as a vehicle to advocate for a number of issues, including promised pay.

The General Society defined broad parameters for its constituent societies, located in each of thirteen states and in France, America’s wartime ally against England. The vast size of the new nation dictated to the General Society’s framers that constituent societies required a good deal of autonomy to manage their own affairs. Eighty-five members of the Pennsylvania Society signed the Parchment Roll, Pennsylvania’s draft of the General Society’s Institution, during a meeting at the City Tavern on October 13, 1783. The Pennsylvania’s Society’s original members, eventually totaling 268, elected Continental Army Major General Arthur St. Clair (1737-18) as their first president and Major General “Mad” Anthony Wayne (1745-96) as his vice president.

Besides presiding over the General Society’s first meeting at the City Tavern, George Washington (1732-99) served as its president general from 1783 until 1799, when Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804) assumed the office. Sixteen members of the Constitutional Convention belonged to the Cincinnati and eleven more became honorary members. The Cincinnati based its state headquarters at the Hill Physick Keith House (321 S. Fourth Street) following the mansion’s restoration in the 1960s.

The Shadow of Cincinnatus

Philadelphia remained central to the societies that veterans formed following the nation’s nineteenth-century conflicts as they sought to preserve the camaraderie experienced in wartime. In a meeting in Congress Hall on January 9, 1854, more than 1,500 War of 1812 veterans created the Society of the War of 1812, a fraternal group for former officers. Attendees elected War of 1812 veteran Joel Barlow Sutherland (1792-61), a former congressman and a founder of Jefferson Medical College, as the group’s first president.

The Aztec Club, formed for officers who served in the Mexican-American War, also congregated in Philadelphia. The city’s Robert Patterson (1792-81), an influential mill owner and an original club member, presided over the organization from 1867 to 1881. Members met annually at Patterson’s mansion at Thirteenth and Locust Streets (later the site for a new building to house the Historical Society of Pennsylvania).

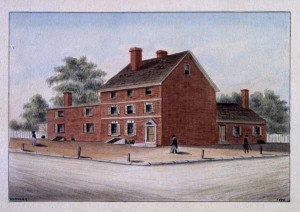

Philadelphia also became the site for the first national home for veterans. In 1826 the U.S. Navy acquired 20.7 acres at Grays Ferry Avenue from prominent Philadelphia Quaker Timothy Abbott (1767-1845) and appointed Philadelphia architect William Strickland (1788-54) as superintendent to build a permanent facility for disabled sailors. The U.S. Naval Asylum (renamed as the U.S. Naval Home in 1889) housed retired sailors until replaced by a new facility in Gulfport, Mississippi, in 1976.

Following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln (1809-65), veterans in Philadelphia held a mass meeting at Independence Hall to pledge renewed allegiance to the Union. This resulted in the creation of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, or the Loyal Legion. Philadelphian George Cadwalader (1806-79), a major general in the Union army, served as the legion’s first commander-in-chief.

Fraternal Gives Way to Activist

As with previous veterans’ organization, the legion welcomed only officers. It deviated, however, by moving toward advocacy on behalf of the general welfare of the Union, its soldiers, and their widows. In this way, the Loyal Legion bridged the earlier veterans’ organizations, which remained exclusive and fraternal, with groups that later proved more inclusive and activist. Its members proved especially concerned with preserving the war’s history by gathering its artifacts.

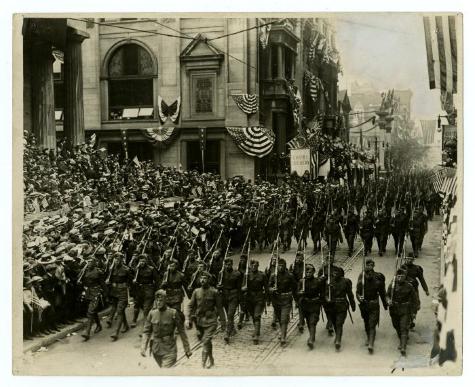

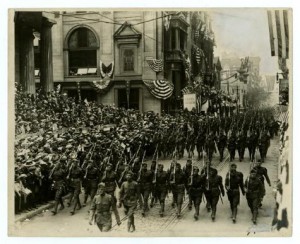

The Grand Army of the Republic formed in Decatur, Illinois, a year after the Loyal Legion’s creation, to advocate on behalf of all Civil War veterans. This established a model for American veterans of ensuing wars who formed the Veterans of Foreign Wars (1914), the American Legion (1919), Vietnam Veterans of America (1978), and Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America (2004). It also built on the tradition of activism exhibited by veterans of earlier wars from the Philadelphia area.

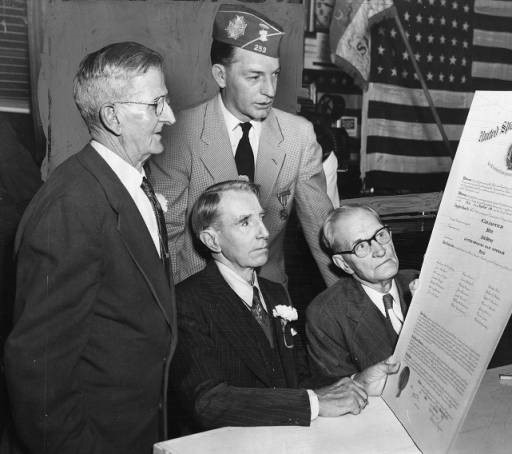

Each new generation of veterans established a presence in the Philadelphia area and set out to serve their communities. For example, the Bridesburg-Lawton Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 2 (4638 Richmond Street), whose members first mustered on July 24, 1902, continued to be active in community service for more than a century. The post’s original leader, Robert S. Hansbury (1863-22), organized the American Veterans of Philippine and China Wars, a forerunner to both the regional American Veterans of Foreign Services and the national Veterans of Foreign Wars created by a national encampment of veterans in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1914. Members of the Bridesburg-Lawton post contributed to the inaugural Philadelphia Veterans Parade (2015) by sending its motorcycle “Riders Group,” the oldest in Philadelphia.

Grand Army Museum

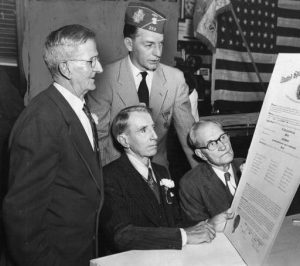

The John Ruan House (4278 Griscom Street), once the home to Philadelphia’s Grand Army of the Republic Post #2, became the Grand Army of the Republic Museum and Library. Post #2 had constituted one of the largest and most influential Grand Army of the Republic posts in the United States. Its members worked to display the many books, artifacts, and memorabilia they collected to educate the public about the war. To ensure the continued maintenance and accessibility of the collection, in 1926 Post #2 members created a corporation, Philadelphia Camp Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War, to carry on their work.

Such engagement was longstanding and widespread. In 1926, the American Legion hosted its first baseball World Series in Philadelphia. This type of civic engagement enabled the legion’s employment committee to lobby successfully for a pledge from the Pennsylvania Railroad to hire a percentage of men over the age of forty during the Great Depression.

Such efforts derived, however, from posts that often remained segregated by race. Initially, policy dictated this. Unable to join Post #2 of the Grand Army of the Republic, in 1867 Philadelphia’s African American veterans of the Civil War chartered Charles Sumner #103. Although the military desegregated in 1953, local veterans’ posts continued to reflect the region’s residential segregation patterns. For example, in 1954, an influx of many Puerto Rican World War II and Korean War veterans in Philadelphia resulted in the creation of Latin American Legion Post #840 of the American Legion.

In the suburbs, the Veterans of Foreign Wars granted separate Black and white posts to Coatesville and Kennett Square. In West Chester, veterans created two American Legion posts within three months of one another in 1919. The Bernhhard F. Schlegel Post 134 began with fifteen members, all white, while fifteen African American veterans created Nathan Holmes Post 362. Still, the two posts worked closely with one another. They jointly orchestrated activities and parades, occupied seats on the county’s veteran council, and sent delegations to the funerals of each other’s members. Their members also joined the same local Veterans of Foreign Wars post.

Soldiering On

The activist spirit promoted by veterans organizations became embraced by individuals such as Philadelphian John Alferi (1881-1974), a World War I veteran and member of the James J. Cochran Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 251. On December 14, 1931, Alferi led a “Veterans’ Bonus Brigade” of fifty veterans on a four-day protest march from Philadelphia to the nation’s capital to call for early payment of bonuses promised by Congress. Although this march attracted little public attention, it inspired an army of veterans who came to call Alferi “Mr. Bonus Army.” The 1931 action inspired the better-known “Bonus Army” march on Washington by thousands of veterans during the summer of 1932.

The region’s activist veterans also included Smedley D. Butler (1881-40), a native of West Chester, Pennsylvania, the most decorated marine in American history at the time of his death. Butler, twice awarded the Medal of Honor, wrote an exposé of war profiteering entitled War is a Racket (1935). Butler supported veterans’ lobbying and visited the Bonus Army while it encamped in Washington to encourage its marchers. He toured the country in 1933 to recruit members for the Veterans of Foreign Wars.

Years later, over Labor Day weekend in 1970, veterans staged another protest march when 150 members of Vietnam Veterans Against the War walked from Morristown, New Jersey, to Doylestown, Pennsylvania, and on to Valley Forge, drawing on the area’s Revolutionary-era symbolism. Aided by the Philadelphia Guerrilla Theater Company, the group dramatized its allegations of the American military’s misconduct in Vietnam, analogous to many acts allegedly perpetuated by the Red Coats in colonial America. At Valley Forge the veterans, joined by over a thousand protesters, conducted a peace rally that featured antiwar speeches delivered by veterans, political leaders, and celebrities.

While the Vietnam War divided the country, Greater Philadelphia’s veterans groups projected unity in lobbying to honor veterans in the naming of the city’s new sports arena completed in 1971. Veterans Stadium served as the home field for Philadelphia’s professional baseball and football teams, the Phillies and the Eagles, until its demolition in 2004.

The unity of Philadelphia area veterans also led to the creation of the Philadelphia Veterans House (4108 Baltimore Avenue) in 1994. Initially a facility to provide short-term housing and meals for veterans commuting for treatment at the Philadelphia Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Philadelphia Veterans House began to provide shelter to homeless veterans in January 2012. Philadelphia Mayor Michael A. Nutter (b. 1957) cited this initiative as essential to his announcement in December 2015 that Philadelphia had effectively ended homelessness among the city’s veterans.

The activist spirit persisted. This was exemplified by the mural Communion Between a Rock and a Hard Place, dedicated in 2012 at 4129 Woodland Avenue near the Veterans Affairs Medical Center. A product of the Philadelphia-based Warrior Writers organization and the City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program, it depicted parallel worlds of Baghdad and Philadelphia: the spheres of soldier and citizen. Philadelphia area veterans worked to bridge these realms from the beginning. They created organizations that became central to serving local communities. Moreover, they effectively raised their voices to address issues of concern to veterans, regionally and nationally. Often they provided models of re-integration for their nation’s other veterans to follow. The history of greater Philadelphia’s veterans, characterized by organization and activism, offered a model for the nation.

Robert J. Kodosky is an associate professor of history at West Chester University. He is the author of Psychological Operations American Style: The Joint United States Public Affairs Office, Vietnam and Beyond. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Delaware veterans honor local marine this Veterans Day (WHYY, November 11, 2011)

- Organization helping injured veterans get on their feet again (WHYY, May 25, 2015)

- Veteran says military gave him the strength to stand up to gentrification (WHYY, August 29, 2016)

- Philly-area groups for veterans and created by veterans provide community, mission (WHYY, September 9, 2016)

- It's all about the training; veterans take to the soil and learn to farm (WHYY, October 31, 2016)

- Victory over veteran homelessness in Delaware (WHYY, November 11, 2016)

- Bringing warmth and love to Philly homeless veterans for Valentine's Day (WHYY, February 14, 2017)

- Ahead of Memorial Day, Americans' confidence in the military unwavering (WHYY, May 26, 2017)

Links

- The Society of the Cincinnati

- The Society of the War of 1812

- Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States

- Veterans of Foreign Wars

- The American Legion

- Vietnam Veterans of America

- Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans Association

- Philadelphia Veterans House

- Philadelphia Veterans Affairs Medical Center

- Warrior Writers