Articles of Confederation

Essay

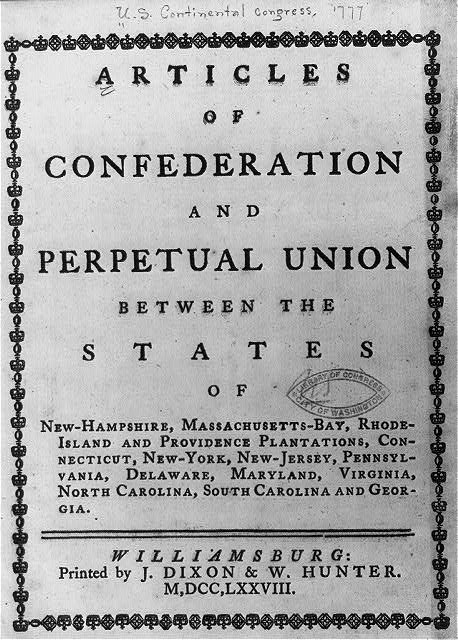

The Articles of Confederation established the Confederation Congress that governed the United States from 1781 to 1789. Meeting in Philadelphia, the Second Continental Congress appointed a committee that began drafting the Articles in 1776. However, the final draft was not complete until 1777 while the Continental Congress was ensconced in York, Pennsylvania, during the British occupation of Philadelphia. The states formally ratified the Articles in 1781, and this compact between the states remained in effect until 1789 when the United States Constitution became the nation’s governing document.

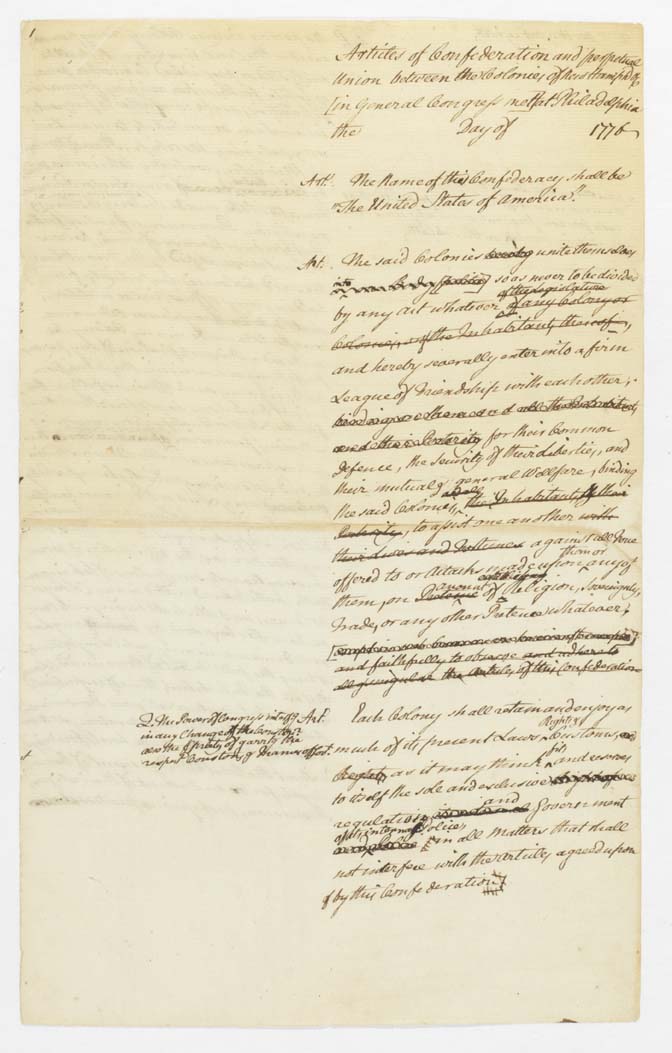

The Continental Congress, meeting in the Pennsylvania State House (later known as Independence Hall), appointed a committee to draft the Articles on June 12, 1776. Philadelphia’s John Dickinson (1732-1808) led the committee that expanded and retooled the ideas for colonial unification that Philadelphian Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) originally proposed to the Congress on July 21, 1775.

Congress, after sixteen months of revisions, finally adopted the committee’s work on November 15, 1777, and two days later submitted the document to the states for ratification. During the years before complete ratification, Congress worked within the framework of the Articles to advance the Revolutionary War effort.

Several small states including New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland initially refused to ratify the document. New Jersey, echoing the sentiments of other holdouts, wanted Congress to control foreign trade and to take possession of any lands that the United States might acquire from Great Britain. New Jersey representatives argued that such powers would give the Congress a means to generate revenue and pay its war debts. These powers would also prevent larger states—particularly those with large port cities and access to western lands—from dominating smaller, coastal states that lacked a major port. The pressing need for unity ultimately led the holdout states to capitulate with the hope that in time Congress would address their concerns.

Complete state ratification of the Articles of Confederation occurred on March 1, 1781, when Maryland, the last holdout state, ratified the document. After ratification, the Congress continued to meet in Philadelphia, but after mid-1783 moved successively to Princeton, New Jersey; Annapolis, Maryland; and Trenton, New Jersey, before settling in New York City from 1785 to 1789.

The confederation that the Articles established was a loose compact between the states. It allowed each state to retain its sovereignty, including the power to tax its citizens, rather than share this legislative power with a national government as the United States Constitution later required. Because of the problems experienced under British rule and Americans’ allegiances to their states, few Americans in the late 1770s and early 1780s wanted a strong national government. Instead, the Articles of Confederation created a single-branch, unicameral institution possessing the power to declare war, to establish foreign and Native American alliances, and to negotiate and approve treaties. The individual state legislatures held all other significant governing authority.

Among the many powers that the states retained under the Articles of Confederation was the authority to control tariffs on foreign and interstate trade. Pennsylvania’s state government profited from this state advantage since tariffs on goods moving through Philadelphia created a sizable revenue stream, but the situation posed a problem for New Jersey residents who paid more for essential goods imported from Philadelphia and New York because of state-imposed tariffs. Tariff wars frequently erupted between states as each attempted to create its own optimal trade markets, and the Articles of Confederation provided Congress no power to resolve these conflicts.

The Articles of Confederation also denied the Confederation Congress the ability to levy direct taxes. While Congress could raise revenue through requisitions sent to the states, no state paid its share in full, and Georgia did not pay any of its required assessment. The United States faced staggering debts after it borrowed large sums to fund the American Revolutionary War. Without revenue from the states, the nation struggled to pay the interest on its loans. Robert Morris (1734-1806), a respected Philadelphia merchant and superintendent of finance for the Confederation Congress, proposed numerous measures to help the United States gain solvency, but Congress and the state legislatures staunchly opposed his proposals.

Congress further struggled to enforce the powers it did have. Although the Articles granted Congress exclusive authority over foreign and Native American diplomacy, New York established its own treaty with the Iroquois, and many states ignored guidelines in the 1783 Treaty of Paris regarding loyalists and British creditors. Lacking the authority to compel compliance, the destitute Confederation Congress quickly lost international credibility and faced a slew of foreign dilemmas. Britain refused to vacate forts and trading posts in the Northwest Territory, Spain limited American access to the Mississippi, and the Barbary States of North Africa seized American ships in the Mediterranean. As the nation teetered on ruin, George Washington (1732-99) remarked that the Confederation was “little more than an empty sound, and Congress a nugatory body.”

On February 21, 1787, the Confederation Congress recognized its deficiencies and called for delegates to meet in Philadelphia to revise the Articles of Confederation. However, the Philadelphia Convention soon embarked on the creation of an entirely new document, the United States Constitution. The framers of the Constitution believed that the Articles of Confederation’s constraint on national power was the primary cause of the nation’s problems. The framers designed a new government that could efficiently raise revenue, settle the nation’s debts, and resolve the domestic and foreign problems plaguing the nation.

While a significant number of Americans harbored deep fears about the powers granted to the new government, the United States constitutional government officially replaced the Confederation Congress on March 4, 1789. This bloodless transition of power helped maintain the fledgling nation’s fragile stability, but the debate over the role and powers of the national government would continue long after the Articles of Confederation became defunct.

Michael DiCamillo is the vice-president of the Historical Society of Moorestown, where he leads educational programs and processes collections for the society’s archives. He also teaches U.S. history courses at LaSalle University and has written for the Journal of Film and History. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Murals of York: The Articles of Confederation (YouTube)

- A More Perfect Union: The Creation of the U.S. Constitution

National History Day Resources

- Draft of the Articles of Confederation by John Dickinson, 1776 (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Primary Documents in American History: The Articles of Confederation (Library of Congress)

- Articles of Confederation, 1777 (National Archives)

- Transcription of the Articles of Confederation (The Avalon Project, Yale Law School)

- New Jersey in the American Revolution, 1763-1783: A Documentary History - see Section XII (New Jersey State Library)