Centre Square Pump House Model

Artifact

Drag across the screen to turn the object. Zoom to view details.

Read more below.

Essay

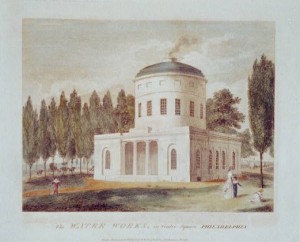

Centre Square Pump House, model by Frederick Graff, c. 1820. (Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent, Historical Society of Pennsylvania Collection, gift of Mrs. Charles Graff, 1942, Photograph by Sara Hawken)

If this model for Philadelphia’s first municipal waterworks brings to mind the Pantheon in Rome, it is no coincidence. The building clearly harkened back to classical Greek and Roman architecture with its unimposing Doric columns and prominent dome. An oculus (round window) at the top of the dome opened to the sky to emit an iconic column of steam from the pump house’s engine. With its symmetry and simple orientation, the neoclassical design of the Center Square Pump House embodied Philadelphia’s classical inheritance as well as its industrial future.

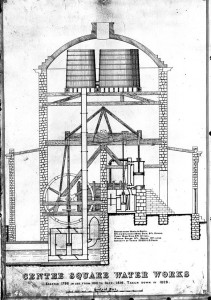

Construction on the Centre Square Pump House began in 1799 and was completed two years later. The building’s marriage of classical aesthetics and functionality reflected eighteenth-century Philadelphians’ conception of their city. At the close of the eighteenth century, Philadelphia faced a rapidly growing population, and with it, a need for clean water sources. The yellow fever outbreaks of 1793 and 1798 highlighted this need, and so Benjamin Henry Latrobe (1764-1820) was hired to design a new water works for the city. A native of England, Latrobe brought a specialized, professional outlook to architecture, disdaining the American inclination to hire the same agent to design and construct a building. Latrobe strictly separated the trades of designing and building, as was the case with the pump house. For this project, Latrobe brought on his assistant engineer, Frederick Graff (1775-1847) – who built this model – and together they designed the city’s first municipal water system to be both useful and elegant.

The pump house sat in Centre Square, one of the five public spaces designated by William Penn (1644-1718) in the original plan for the city (and later the site of Philadelphia’s City Hall). A series of pumps moved water up from the Schuylkill to the pump house, which then distributed clean water via wooden pipes to water hydrants and paying subscribers, including four breweries and a sugar refinery.

Despite its early promise, the pump house faced a number of issues with its steam engines, which proved rather unreliable and required significant maintenance. By 1815, it became clear that a different solution would be needed. Graff, who by then had become the superintendent and head engineer of the project, encouraged the construction of the more efficient and reliable Fairmount Water Works. The city’s second municipal works opened in 1815 and stood on the Schuylkill just below the later site of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. After the switch to Fairmount Water Works, the city continued to use Centre Square Pump House as a distribution point for seventeen more years. The building was finally demolished in 1829. Fairmount was a more successful municipal waterworks, remaining in operation until 1909 and later becoming the site for an aquarium, a pool, a restaurant, and an interpretive center.

Though it stood for only twenty-nine years, the Centre Square Pump House embodied Philadelphia’s role as a birthplace of creative and revolutionary energy. At the close of the eighteenth century, many eyes were on the city that fostered the spirit of political freedom during the American Revolution and then served as the nation’s capital. Political leaders had long been known to borrow the trappings of classical Greece to enforce an image of longstanding power and authority. This began with fresh gusto when the Peales and other prominent portrait painters paired Philadelphia’s leaders with columns and imagery that recalled Greece’s golden age. Classical architecture and institutions such as the Philadelphia Athenaeum (founded in 1814) also contributed to the city’s moniker as the “Athens of America.”

The Centre City Pump House, though ultimately short-lived, proved that a municipal waterworks system was a valuable service to a growing city. It helped build an architectural movement in the city that tied Philadelphia to that faraway birthplace of democracy. Equally notable is that it brought Benjamin Latrobe to the area to spread his practice of separating design and construction, a system that endured in many building projects in the United States.

Text by Kelsey Ransick, museum professional in the Philadelphia area with an MA in History from the University of Delaware.

Click on the base of the model to explore the building that stands on the site of the pump house today.