Draft Drum

Artifact

Drag across the screen to turn the object. Zoom to view details.

Read more below.

Essay

Civil War Draft Drum, likely used in the First and Second Districts of Pennsylvania. (Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent, Historical Society of Pennsylvania Collection, Photograph by Sara Hawken)

A number of Civil War-era draft drums (often referred to during the period as “draft wheels,” “draft boxes,” or “wheels of destiny”) have survived around the United States. New York City draft drums have become especially prized because of their relationship with that city’s draft riot in 1863. While reaction to the draft in Philadelphia was not nearly as dramatic, the Philadelphia drum pictured here, likely used in the FIrst and Second Congressional Districts (but possibly throughout the city), serves as a reminder of how Philadelphians dealt with the draft and ultimately how a majority of Philadelphians came to support the war effort despite antebellum political and economic connections to the South similar to New York.

When Congress passed the Militia Act in July 1862, authorizing states to draft from their militias to fill each state’s quota of volunteers, Philadelphians had not experienced a draft or a direct military threat since the War of 1812. Most Philadelphians could not remember a time when there had been a draft, and few remembered details of past militia laws. During the Revolution and the War of 1812, Philadelphians had been subject militia drafts. During the Revolution, all white males between the ages of 18 and 53 were subject to the draft. When called, drafted men could hire substitutes to take their place. If the person was drafted into the militia he was expected to serve two months, but if he was drafted into the Continental Line, he was expected to serve seven or nine months. During the War of 1812, drafted militiamen were expected to serve no more than three months. After the War of 1812, the term was extended to a maximum of six months, but that never affected Philadelphians. When the new law in 1862 called for draftees to serve nine months, it was not an unprecedented amount of time, but Philadelphians would have needed long memories to recall the last time they had been asked for that period of service.

Few Philadelphians doubted the legality of the draft, but some Philadelphians, typically “Peace” Democrats who questioned the conduct and necessity of the war, opposed it. In response, some Philadelphia Republicans and members of the National Union Party (a pro-Union Philadelphia coalition party made up of Whigs, Republicans, and disaffected Democrats) argued that mass conscription was necessary to win the war. To back up their claims, they cited the success of Napoleon’s conscripted army and reminded other Philadelphians that only fifty years earlier, there was, in fact, a draft. Nearly all Philadelphians agreed that a draft would fall hard upon Philadelphia’s middle and lower classes and the effect of the draft would have to be mitigated in some way.

For many, the best way to mitigate the effects of the draft was to avoid it all together. Drawing upon Philadelphia’s earlier experience with the draft and the city’s tradition of volunteerism, Philadelphians began raising money to pay incentives to men willing to enlist voluntarily. Eager to display Philadelphia’s patriotism to the rest of the country and spurred on by fears of social unrest and dislocation connected with the draft, Philadelphians participated in ward meetings to encourage suitable men to volunteer, raise bounties for enlistees, and raise funds to take care of families that might be affected by the draft. By 1862, war contracts had inaugurated a period of prosperity in the city that lasted until the end of the war, and this enabled elites, the middle class, and portions of the working class to donate to bounty funds and later to pay their way out of the draft entirely.

In August 1862, deputy provost marshals enrolled Philadelphia’s white males aged 18-45 into the militia. It was probably around this time that the draft drum pictured here, now in the Philadelphia History Museum’s collections, was built for use in at least the First and Second Congressional Districts. These two districts were nearly opposites when it came to the wealth of their inhabitants. The First Congressional District included the Second, Third, Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, and Eleventh Wards (Moyamensing and Southwark), and the riverfront portions of Northern Liberties and Philadelphia city districts east of Seventh Street; the Second Congressional District covered the First, Seventh, Eighth, Ninth, and Tenth Wards, essentially everything below Wharton Street bounded by the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers plus the area between South and Vine Streets west of Seventh Street to the Schuylkill. The Second District, the Philadelphia Inquirer noted in 1863, had perhaps “the greatest wealth in the city” and “the aristocratical mansions of Walnut, Chestnut and Arch streets.” In contrast to the upper and middle class residents, relatively new housing, and spaciousness of the Second District, the densely populated, mostly working-class First District had a reputation as a slum with buildings that were among the oldest in the city.

In this era following the city consolidation of 1854 and redistricting, the First District was typically a Democratic stronghold, with many immigrant, working-class voters, while the Second District typically voted Whig. After the Whigs dissolved in the 1850s, the Second District voted Democratic in 1861, but then shifted in 1863 to the National Union Party as many of the district’s voters remained suspicious of the anti-slavery Republicans As the war and the draft unfolded, the two districts became Philadelphia’s barometer of the city’s pro-war or anti-war feeling. If any active resistance to the war was going to appear, it was widely assumed that it would happen in one of these districts, but particularly the 1st.

The only major violence associated with the draft in Philadelphia during the entire war took place not in 1863, as might be expected, but on August 29, 1862, in one of the wards that used this draft wheel: the Second Ward of the First Congressional District. When marshals began enrolling men into the militia, they were pelted with rocks by men and women near Eleventh and Montrose Streets in South Philadelphia. Injuries and arrests resulted, but no fatalities. Military provost marshals and city police quickly quashed even the slightest evidence of resistance.

By the time the draft in Philadelphia approached in September 1862, the city was a hectic place: Philadelphians raced to build their bounty fund and to enroll as many volunteers as possible to fill the city’s quota and avoid a draft. At the same time they steeled themselves to resist a possible Confederate invasion of Pennsylvania. By the end of September, news of the Confederate invasion of Maryland and subsequent Union victory at the Battle of Antietam overshadowed the draft. Finally, after several postponements to allow for continued recruiting and to double-check recruitment numbers, Philadelphia’s draft was canceled because the city had met its quota through volunteers.

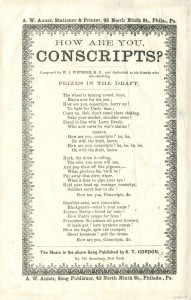

By the end of 1862, the United States government determined that it still needed more men to crush the rebellion A new law passed in March 1863, the Enrollment Act, seemed to some citizens like a radical break with the past. Draftees would serve for three years, but like earlier American drafts, the new law provided incentives to enlist as well as many mechanisms to avoid service that largely favored the well-off. While those who created the law considered a fee of $300 to avoid service to be well within the means of working men, it seemed to many in Philadelphia’s poor and working class that the rich and poor bore unequal burdens in a fight for the freedom and equality of African Americans. Philadelphia Peace Democrats had always argued that the Republicans were would-be tyrants and that the war was being fought for the equality and freedom of African-Americans. Now, with the Emancipation Proclamation and harsher and occasionally unprecedented war measures like the draft, they thought that their predictions of Republican tyranny had come true and encouraged resistance. In Democratic areas, such as the First Congressional District, Philadelphians went to great lengths, including changing names and locations, to avoid the draft. In contrast, Republican papers argued that conscription had precedents and the draft was necessary to win the war and was generally accepted in Republican districts.

In 1863, as in the year before, Philadelphians relied on volunteerism to avoid the draft with little in supplementary funds from Philadelphia’s city budget. Rallies raised money to increase enlistment bounties and to provide for soldiers’ families. By July 1863, however, as bounties inflated nation-wide, it became apparent that a draft would be necessary. As Philadelphians celebrated the Union’s victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, Miss., they began to prepare for their first draft in nearly fifty years, scheduled for mid-July.

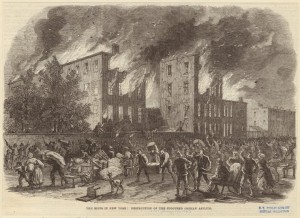

Meanwhile, news also arrived of the violence in New York City on July 13, two days after the start of that city’s draft. Philadelphians feared a similar outbreak of violence in Democratic and immigrant neighborhoods. Even after the draft began in Philadelphia without signs of imminent violence, the newspaper of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the Christian Recorder, warned its readers that white Philadelphians would “not only resist the draft, but will pounce upon the colored people as they did in New York, and elsewhere.” Like New York, Philadelphia had strong political ties to the Southern Democratic Party, economic ties to slavery, and abolitionists who had been targets of ire by many of the city’s whites. However, unlike New York, much of Philadelphia’s anger had shifted away from abolitionists and the nascent Republican Party toward secessionists and people perceived to be their abettors, Philadelphia’s “Peace” Democrats. Further, the victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg elated the city and quieted the war’s critics.

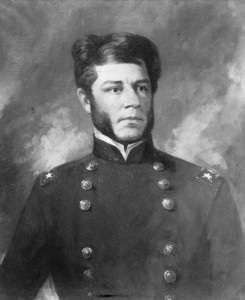

Fearing the same sort of violence that New York was experiencing, the First Congressional District’s Provost Marshall, former Democratic Congressman William Eckart Lehman (1821-95), warned that the “1st Dist[rict] contains the worst population in the state, and reports are brought to us (but what they are worth is hard to say) of threats of riot, accumulations of arms, etc.” To discourage trouble, the Army sent several regiments of infantry and cavalry and several batteries of artillery to Philadelphia, although they did not arrive until after the draft had begun. Lincoln appointed a popular Philadelphia Democrat, General George Cadwalader (1806-79), as commander of the Philadelphia military district. Cadwalader, a scion of one of Philadelphia’s most powerful families, a Mexican War hero, and the antebellum commander of Philadelphia’s militia, had led the militia that put down the 1844 nativist riots. City elites confidently expected that he would do the same for any draft-related riots.

With an expanded, empowered police department, provost marshals, soldiers ensuring order, and a predominantly loyal city, Philadelphia experienced no notably violent draft-related disturbances from 1863 until the end of the war.

The draft began as scheduled in “loyal” districts in mid-July. Even in purportedly less fractious areas, like the Frankford section of Philadelphia, military forces monitored the execution of the draft to deter to any would-be rioters. The draft did not reach the First or Second Congressional Districts until July 28, and by then tension had declined to the point that troops stationed in Philadelphia for the draft were sent elsewhere. Philadelphia emergency troops raised to meet the Confederate invasion were sent to the anthracite coal district in Northeast and North Central Pennsylvania to guard against any draft disturbances there. When the draft finally reached the First and Second Congressional Districts, it went over with an ease that defied expectations.

The mechanism for the draft in these districts, and possibly most of Philadelphia, was the draft drum at the top of this page. This drum, resembling a cheese box or hat box of the period, was described during the period as “a box” and a “wheel.” While we cannot be certain, evidence suggests that this draft drum was used throughout most of the city because accounts of draft drums used in other congressional districts describe a similar, easily portable “tin wheel” of “about two feet in diameter.” Because of its light weight and portable construction, it could have been easily transported from congressional district to congressional district. With the exception of the days the draft was held in the Fifth Congressional District, which also included parts of Bucks County, the draft took place in Philadelphia one precinct at a time, so only one draft drum would have been necessary to carry out the draft for most of Philadelphia.

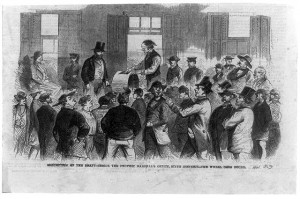

Use of the draft drum followed a standard process. On the day of the draft, the drum was moved to a platform outside the provost marshal’s office in the congressional district where a ward’s draft was to take place. A crowd of usually a few hundred people gathered to watch the proceedings, which were also attended by the provost marshal, all of the draft commissioners, and other ward representatives. Slips of paper, each of with the name of an eligible man, were placed inside the drum and then jumbled by turning the crank for several minutes. To ensure fairness, representatives of the ward’s political parties observed on the platform, and a blind man placed his hand inside the drum’s opening to pick out the names. After the ward filled its quota, typically after several hours, officials counted the unpicked slips of paper to further verify the fairness of the proceedings.

The draft in the First District did not erupt in violence, contrary to Provost Marshal Lehman’s fears. If the Republican-friendly newspapers were accurate, the 1st and 2nd Districts showed evidence of enthusiasm. In the Fifth Ward of the First District, the Inquirer reported, “Mr. Parvin [the blind person chosen to pick names out of the wheel] sang ‘the Lafayette Song,’ which he stated he sang when he was ten years of age—during LaFayette’s visit to this country. At the conclusion he was called on by the crowd for the Star Spangled Banner, which he also sang with great spirit. The crowd then dispersed amid great enthusiasm.” As the draft continued, newspapers began to compare Philadelphia and New York again, only this time to put Philadelphia’s loyalty in sharp relief. Philadelphians happily contrasted their enthusiasm and order with New York’s bloody riots: “The Quaker city may congratulate itself that the proud name which it has earned as a law-abiding people received new distinction,” the Inquirer boasted.

By early August 1863, Philadelphia completed its draft. More than 20,000 men had been chosen from Philadelphia’s five congressional districts. Those selected had several weeks to hire a substitute, pay a $300 commutation fee, or to show medical reasons that made them not fit for the service. According to historian J. Matthew Gallman, of the tens of thousands chosen, only 21 percent (4,169) were made to join the Army, find a substitute, or pay a $300 commutation fee. Of that total the far majority chose to find a substitute or to pay the $300 commutation fee as only 343 people drafted actually entered the Army Compared to the rest of the state, Gallman concluded, in 1863 Philadelphia and Bucks County (which was part of the shared Fifth Congressional District) provided 28.8 percent of Pennsylvania’s quota but only 9.8 percent of Pennsylvania’s draftees, a testament to the effectiveness of the Philadelphia’s voluntarism and wealth.

To keep Philadelphia’s bounties competitive with neighboring areas, the City Council began paying a greater share of bounties as voluntarism could no longer keep pace. In 1864, the city dedicated nearly half of its budget to pay bounties and support families of soldiers. The lucrative bounties, often around $1,000, enabled Philadelphia to weather the drafts of 1864 with little problem. After the Union asked for 500,000 more volunteers in February 1864, only the Fifth Congressional District was forced to draft, and only fifteen men were forced to serve. By February 1865, when the last draft took place in Philadelphia, the rebellion was nearly crushed. The draft took place in the First, Second, and Fifth districts, and it provided a little under 500 men.

After 1865, Philadelphians did not participate in another draft until 1917 (for World War I) and then 1940 (prior to U.S. entry into World War II). By that time, memories of the Civil War draft had faded, along with this draft drum. Sometime after 1865, this draft wheel was donated to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. During renovations in October 1940, it was rediscovered along with posters offering bounties to men who would volunteer instead of waiting to be drafted. Coming to light merely weeks after the enactment of the first peacetime draft in American history, the wheel and posters became relevant again and displayed in an exhibit about Philadelphia’s Civil War-era recruiting practices. Never again lost from memory, the draft drum remained in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s artifacts collection, later transferred to the Philadelphia History Museum.

Text by Matthew C. White, who earned his M.A. in history at Rutgers University-Camden.