Automotive Manufacturing

By Stephen Nepa

Essay

Once a mainstay of Greater Philadelphia’s industrial might and a reflection of the socioeconomic transformations of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, the manufacturing of automobiles and related components provided mobility for millions, jobs for many thousands, and lifeblood for towns and cities. First appearing in the 1900s, flourishing during the interwar and postwar periods, and declining after the late 1970s, car and truck making in Greater Philadelphia, with few exceptions, nearly disappeared by the 2010s.

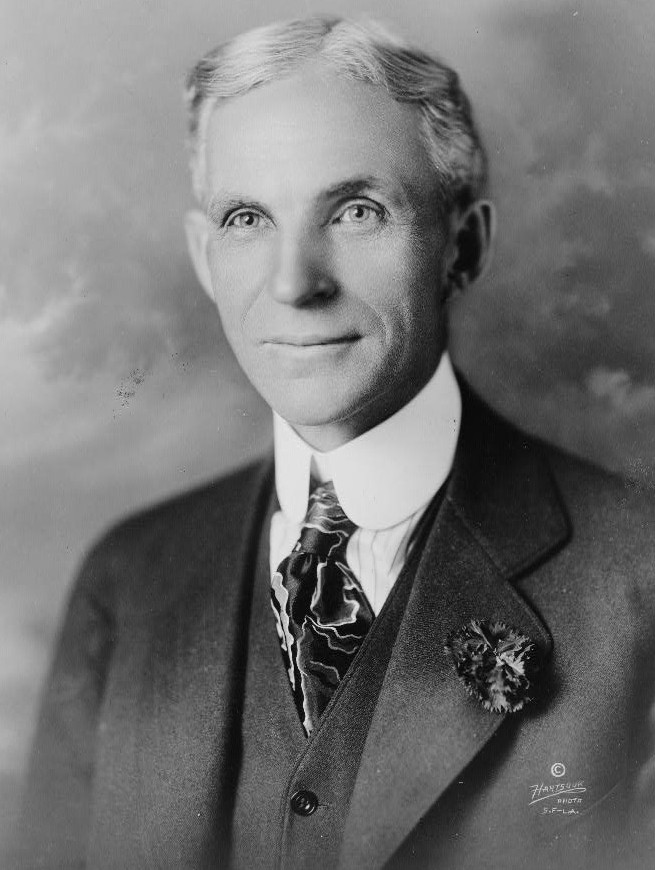

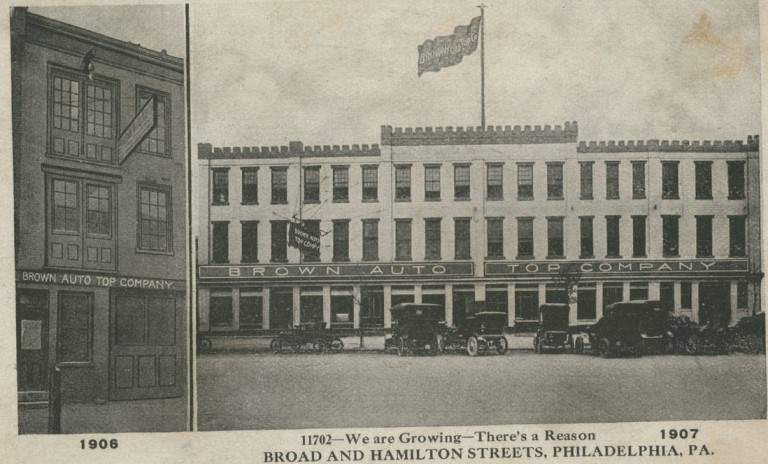

Prior to the assembly-line techniques perfected by Henry Ford (1863-1947), few automakers controlled all aspects of production. Instead, parts, from chassis to headlights, came mainly from individual companies. In 1906 the Philadelphia Storage Battery Company shipped its first electric car battery to Baker, a Cleveland-based carmaker; three years later, production moved from Tioga and Emerald Streets to a larger plant at Tioga and C Streets. Starting in 1919, the company stamped “Philco” onto each battery. Philco shifted production to car radios in 1926 and, after pioneering permeable tuning and high-fidelity sound, emerged as the world’s largest car radio maker. Camden, New Jersey’s RCA, producing less than half of Philco’s output in the 1930s, ranked second. Such prominence attracted the Ford Motor Company, with whom Philco signed an exclusive contract for audio components in 1934. The nearby Budd Company, founded in 1912 by Edward G. Budd (1870-1946), specialized in car bodies. With early bodies comprised of wood, Budd’s all-steel frames caused a sensation when, in 1916, John (1864-1920) and Horace (1868-1920) Dodge ordered 70,000 units for their touring sedans. From its Hunting Park factory complex containing nearly 7,000 workers, Budd supplied bodies to U.S., British, and German carmakers into the 1950s.

In addition to parts manufacturers, small carmakers and regional operations for larger companies opened in Greater Philadelphia. New Jersey hosted more than fifty car-making interests between 1900 and 1950, although most were located in the northern and central portions of the state. South Jersey enterprises included Trenton’s Walter Automobile, which collapsed in 1917, and the Mercer Automobile Company (also of Trenton), which, backed by the Roebling family, endured until 1929. Equally important in early 1900s transportation were trucks, which over time rendered horse-drawn vehicles obsolete. After purchasing a Brooklyn-based carriage builder and expanding operations to Allentown, Pennsylvania, in 1905, John Mack (1864-1924) and his brothers commenced production of their eponymous trucks. By 1938, Mack’s AC model made the company internationally famous.

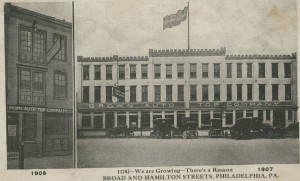

Ford Opens an Office, 1906

The Ford Motor Company became the first of the “Big Three” U.S. automakers to establish a presence in the region. In 1906, two years before its Model T debuted, Ford opened a sales office in Philadelphia. When World War I began, Ford’s Model T production alone outpaced all other automakers’ efforts combined, prompting the company to open additional assembly plants. In 1914, after designing the Packard Motor Company showroom at Broad and Spring Garden Streets, architect Albert Kahn (1869-1942) designed a factory for Ford at Broad Street and Lehigh Avenue. At capacity, the Lehigh plant produced 150 Model T units per day. Following American entry into the war, the U.S. Ordnance Department took over the factory to manufacture helmets, body armor, and machine-gun trucks. In 1925, needing more space and hoping to ship vehicles more efficiently, Ford transferred operations to Chester, Pennsylvania, on the Delaware River. Until the outbreak of World War II, workers at Chester assembled various Ford models with parts produced at River Rouge, Michigan. General Motors (GM), whose area operations expanded after 1945, arrived in 1938 with a components factory at West Trenton, New Jersey.

World War II and its aftermath greatly affected local automobile manufacturing. In 1942, the U.S. Ordnance Department again commandeered factories, using Ford’s Chester facility to prepare tanks and military vehicles and GM’s West Trenton plant to build torpedo bombers. After the war, carmakers increased regional operations to meet the demand created by the postwar baby boom, expansion of the American middle class, and suburbanization. While existing plants returned to peacetime production, GM and Chrysler opened new factories in Wilmington, Delaware (1947), and Newark, Delaware (1952), respectively. By the 1960s, automobile manufacturing emerged as the largest industry in Delaware, second only to the DuPont Corporation’s chemical plants. Parts manufacturers, including Budd, Mopar, and Lears Auto Parts of Newark, also thrived in the early 1950s. Yet Philco, which began the decade soundly, collapsed spectacularly by 1960 due to overexpansion and diversification into other industries. In 1961, the remnants of the company were acquired by Ford, which that year shuttered its Chester facility to consolidate operations in Mahwah, New Jersey.

Auto Factories Fade Away

By the late 1970s, due to labor issues, gas shortages, and the arrival of fuel-efficient foreign imports, U.S. auto manufacturing entered a protracted decline. Though Ford opened a new plant in Lansdale, Pennsylvania, in 1989, it was among the closures in the 1990s and early 2000s that also affected West Trenton, Wilmington, and Newark. Negotiations between union leaders and executives temporarily saved the factories, but foreign competition, labor outsourcing, and consumer tastes remained obstacles. In 1998, GM closed its West Trenton factory; the building was demolished in 2000. Budd’s Hunting Park complex ceased production in 2002 after its parent company consolidated its U.S. operations in Michigan. In February 2007, Chrysler announced the closure of its Newark facility and in July 2009, GM permanently idled its Wilmington plant, the last active auto factory in the eastern United States. Together, the three closings affected more than 10,000 workers. By early 2010, Greater Philadelphia’s only remaining car or truck assembly interest was Mack, which still built trucks at its one-million-square-foot plant in Macungie, Pennsylvania.

Though many former car factories stood vacant after 2010, others were repurposed. One year after its closing, California-based Fisker Automotive, a luxury marque, acquired GM’s Wilmington plant. However, Fisker declared bankruptcy in 2013 and sold the facility to Chinese auto parts maker Wanxiang, confirming the global scope of industry competition. In 2011, Chrysler’s Newark factory was partly demolished; its remaining sections were used in the construction of the University of Delaware’s College of Health Sciences.

For decades, Greater Philadelphia’s carmaking operations, from parts factories to assembly plants, in peacetime and war, played invaluable roles for workers, lifestyles, and commerce. By the early decades of the twenty-first century, the few surviving physical remnants of the industry served as a reminder of the region’s once-critical role in automobile manufacturing.

Stephen Nepa received his M.A. from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and his Ph.D. from Temple University and has appeared in the Emmy Award-winning documentary series Philadelphia: the Great Experiment. He wrote this essay while an associate historian at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Center for the Humanities at Rutgers University-Camden in 2015. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University