Philadelphia Board of Health

Essay

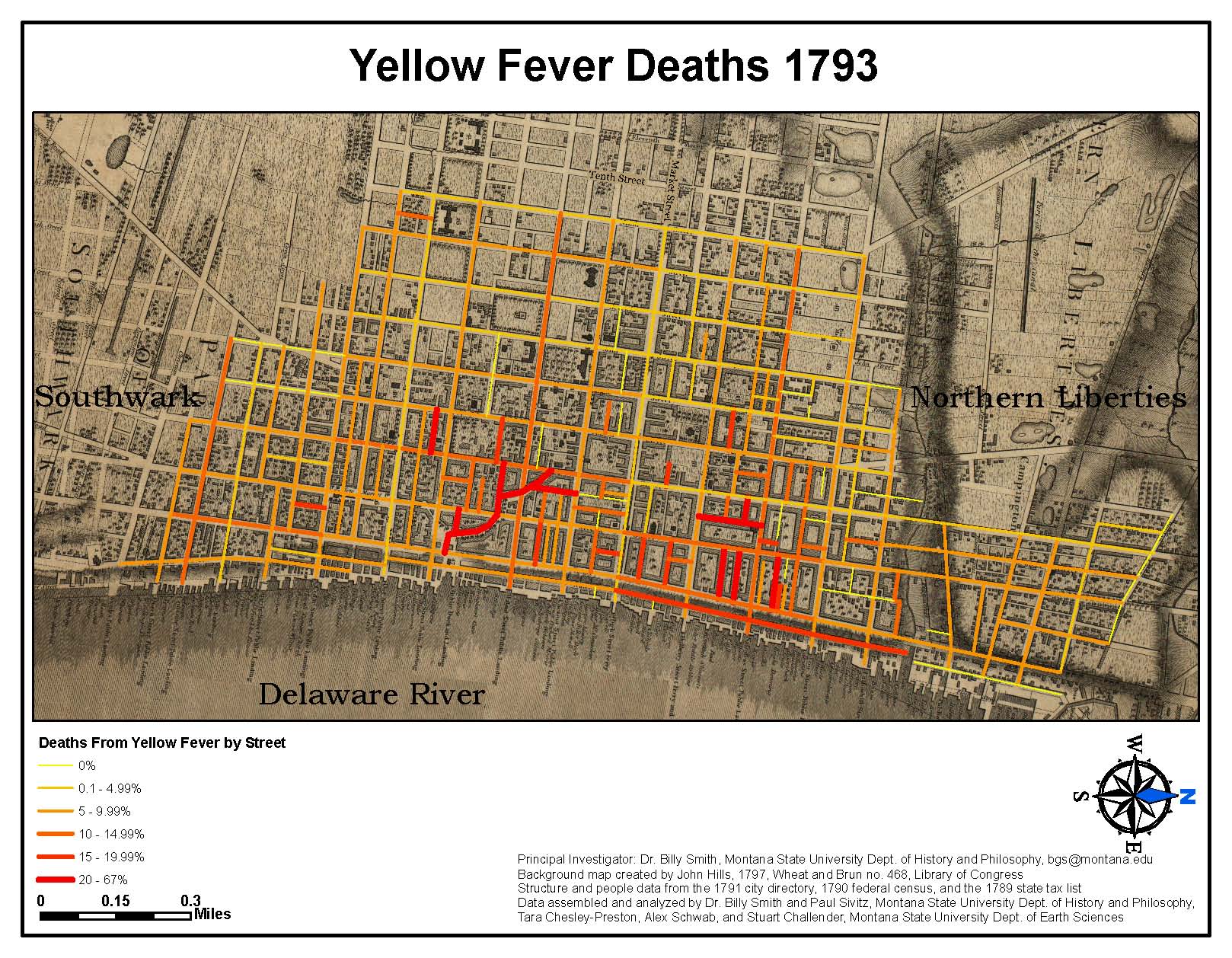

Philadelphia suffered numerous outbreaks of epidemic disease throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but it was not until 1794, in the wake of the disastrous 1793 yellow fever outbreak, that a group of concerned citizens founded the Board of Health, independent of the city’s control. In the nineteenth century, the city supported the board with an annual budget and continuously expanded its responsibilities to include sanitary and housing inspection, epidemic control, and management of several hospitals. By the turn of the twenty-first century, the renamed Department of Health participated in antiterrorism exercises, anti-heroin initiatives, and gun violence reduction programs.

During its first decades, the Board of Health was most energetic during outbreaks of infectious disease, such as yellow fever, smallpox, and diphtheria, which it confronted with quarantines, removal of the indigent sick to hospitals, and burning smudge pots. In 1797, the city changed the board’s title to the Managers of the City and Marine Hospital and charged it with ship inspection and isolation/treatment of ill passengers. Again named the Board of Health in 1804, the board engaged in little preventative health work, as the city did not empower it to make sanitation laws.

Cholera offered the greatest challenge to the board when it arrived in 1832 and provoked a round of street cleansing and fumigation, which, though offering the appearance of a response, did nothing to beat back the disease. By the third cholera epidemic of 1866, however, science began to offer new explanations of disease causation and control. For instance, the theory of contagion—that diseases spread from person to person—came to dominate scientific circles, which also began to suspect the role bacterial pathogens played in infectious disease.

The revolutions in medicine offered the first solid theoretical foundation for modern public health efforts in Philadelphia. For instance, the board, which had recorded deaths since 1838, began in 1865 to record marriages and births, too. It continuously refined the categories of causes of death as diseases, many of which produced similar symptoms, were recognized as distinct ailments. In 1866 the city opened the Philadelphia Municipal Hospital for Contagious Disease at Twenty-Second and Lehigh Streets under the management of the board’s growing cadre of physicians and nurses.

During the last two decades of the nineteenth century, however, as massive numbers of immigrants packed into tenements, the board struggled with diseases that threatened outbreaks. It had little power to effect real change in the city’s housing and sanitation and therefore dealt with diseases and other threats after they emerged, as smallpox and typhus did during the 1890s.

In 1903, the state legislature centralized Philadelphia’s charity and health operations and placed such work under the aegis of the Department of Health and Charities. The department had expanded responsibilities, including operation of the city’s workhouse, increased responsibility for housing and food inspection, and the power to create and enforce health regulations. The department repeatedly called for water purification (accomplished by 1912), pressed for a new Municipal Hospital for Contagious Disease (opened in 1911 at Second and Luzerne Streets), and fought for general sanitary improvement of the city. The department’s greatest challenge was the 1918–19 influenza epidemic that killed roughly fifteen thousand residents. Although one other major city, Pittsburgh, suffered a slightly higher death rate, Philadelphia’s outbreak resulted in hundreds of corpses laying in cramped apartments and mass graves, phenomena not experienced in other American or European metropolises.

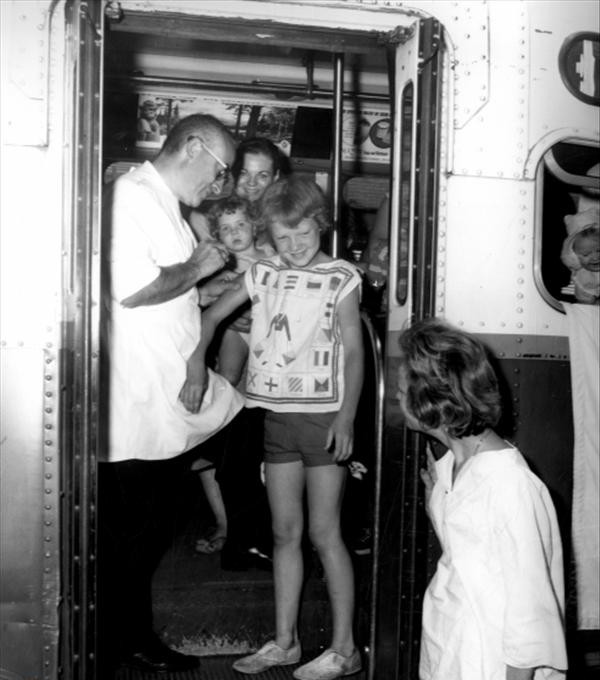

In the wake of the pandemic the board was once again reorganized, this time as the Department of Health. The department offered badly needed health resources during the Great Depression, when large numbers of Philadelphians could ill afford medical fees. Throughout the mid-twentieth century, clean water, sanitary disposal of waste, inoculations, and antibiotics, as well as physicians’ resistance to tax-funded competition, relentlessly reduced the need and power of the department. Furthermore, the flight of working- and middle-class residents to the suburbs and the flood of drugs, especially heroin, into the city changed the nature of its health threats.

While the advent of clean water, sanitary disposal of waste, inoculations, and antibiotics have greatly improved public health, outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease and HIV/AIDS, to say nothing of the daily need to monitor restaurants, schools, buildings, and other possible sources of disease and injury, have demonstrated the continuing need for vigilance. In the wake of the September 11 attacks, the Philadelphia Department of Health partnered with law enforcement to refine responses to terrorist attacks. It also led a coordinated campaign to reduce gun violence, especially among the city’s poor children and young adults. These challenges highlighted the continuing need for a city board of health.

James Higgins is a lecturer in American history at the University of Houston–Victoria. He specializes in the history of medicine, especially as it pertains to Pennsylvania. His manuscript, which analyzes four urban outbreaks in Pennsylvania during the 1918–19 influenza pandemic, is with the University of Rochester Press. He has offered a dozen conference papers and several articles, invited lectures, and book chapters. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

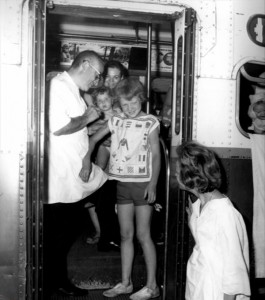

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- By the numbers: HIV/AIDS stigma changing, but infection still spreads (WHYY, December 20, 2013)

- America's oldest quarantine hospital tied to Philadelphia yellow fever history (WHYY, January 9, 2014)

- Philadelphia Health Department pursues national accreditation (WHYY, May 5, 2014)

- Philadelphia's Department of Behavioral Health broadening approach to care (WHYY, November 27, 2015)