Christiana Riot Trial

Essay

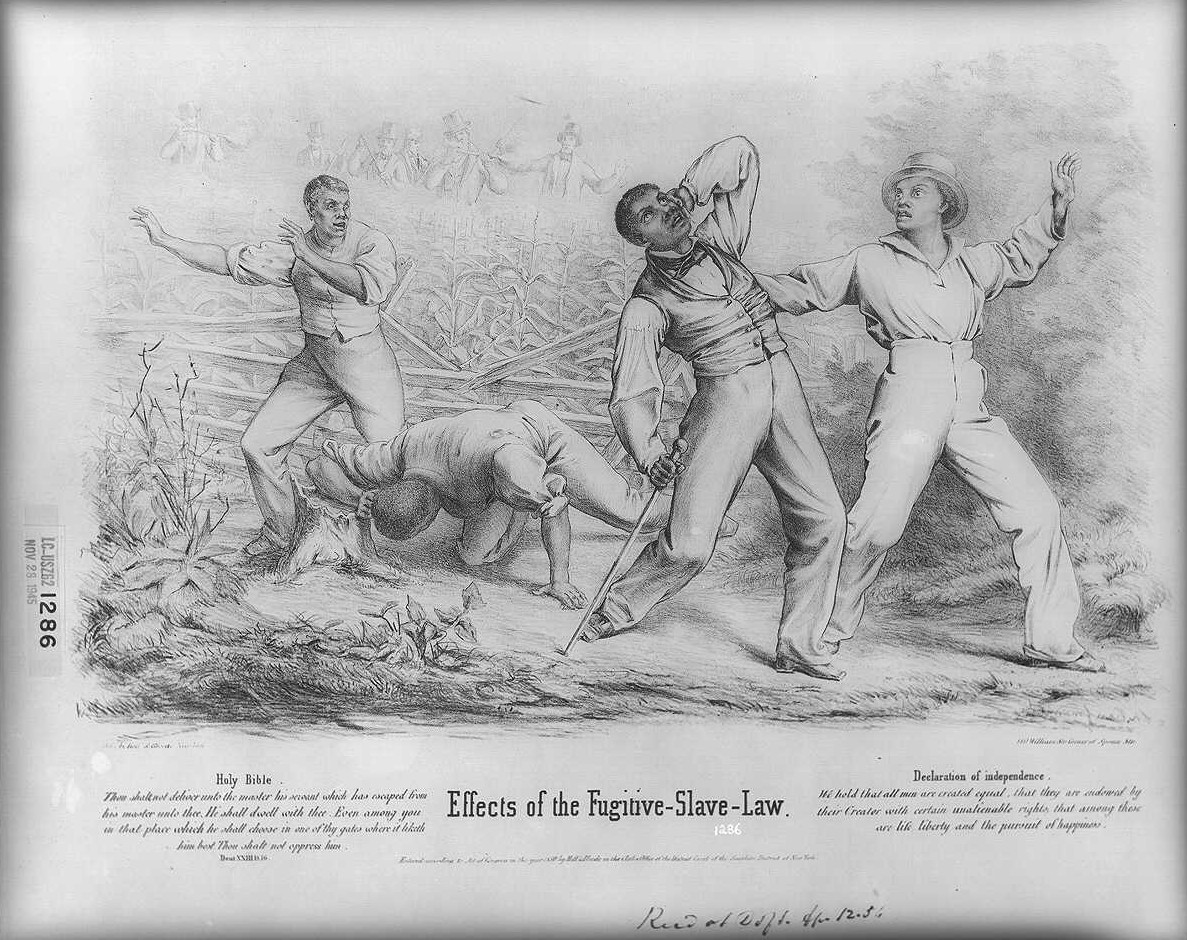

During the 1850s, Northern abolitionism developed, Southern defense of slavery hardened, and debates over the expansion of slavery gripped the nation. When pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions met at Christiana, Pennsylvania, a mere 20 miles north of the Mason-Dixon Line, the events that followed and the subsequent trial in Philadelphia became flashpoints that deepened the sectional divisions between the North and South.

On September 11, 1851, slaveholder Edward Gorsuch (1795-1851) and his party of eight men rode into Christiana from Baltimore County, Maryland, with warrants for the arrests of four fugitive slaves. Upon reaching the home of William Parker (1822-?), a fugitive slave, Gorsuch and his party were met with armed resistance. A large group of armed Black men and women surrounded Gorsuch’s party and demanded that they leave Pennsylvania immediately. When Gorsuch refused to vacate Parker’s property, chaos ensued. Indeed, Gorsuch’s men fired guns as Black men and women attacked Gorsuch’s party with clubs, corn cutters, and other crude weapons. While accounts of that day conflict, numerous individuals on both sides of the battle were injured and Gorsuch died of wounds sustained during the fight.

In the immediate aftermath of the Christiana Riot, Parker and two other men, presumably fugitive slaves, escaped for Canada. U.S. officials hastily arrested anyone possibly connected with the riot, including a white miller from Christiana named Castner Hanway (1821-93). Hanway, who rode to Parker’s home on the day of the riot, was mistakenly identified as the mastermind of the riot. Along with forty-one other men, Hanway was charged with treason for “wickedly and traitorously” intending “to levy war” against the United States. Hanway’s trial began on November 24, 1851, at the old Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia (Independence Hall) with Supreme Court Justice Robert C. Grier (1794-1870) and U.S. District Court Judge John K. Kane (1795-1858) presiding.

The defense of the Christiana Riot participants became a popular cause for the abolitionist movement. Fiery abolitionist and U.S. representative for Lancaster County Thaddeus Stevens (1792-1868) led Hanway’s defense team, and abolitionist Lucretia Mott (1793-1880) sat in the courtroom on the second floor of Independence Hall throughout the trial. The prosecution was directed by the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, John W. Ashmead (1806-68), and a team of lawyers from the state of Maryland. After opening arguments, Ashmead called the prosecution’s key witness, U.S. Deputy Marshal Henry Kline (1820-85), to the stand. Kline had been among Gorsuch’s party on the day of the riot and testified that Hanway was responsible for inciting Parker and the resisters. Under cross-examination, Kline admitted that he had hidden in a cornfield during the riot, so his view was obstructed. Following Kline’s testimony, the defense called twenty-nine character witnesses, including Judge William D. Kelley (1814-90), who portrayed Kline as a liar and a known kidnapper. This testimony was devastating for the prosecution. Indeed, for many Pennsylvanians—even those who were not in sympathy with the abolitionist cause—there was little interest in prosecution, because the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law seemed to represent an incursion of federal power into state sovereignty. After fifteen minutes of deliberation by the jury, Hanway was found not guilty of treason. Subsequently, federal and state officials declined to press further charges against the riot participants.

The verdict served as a fuel for the abolition movement as it gained momentum in the 1850s. The events at Christiana also showed that African American men and women could organize themselves to actively resist any attempts to kidnap fugitive slaves or disturb their communities. Nevertheless, Southerners viewed the verdict as a product of Northern radicalism and a failure to equally apply the law. The sectional divisions made clear by the Christiana Riot trial deepened throughout the 1850s and ultimately led to the Civil War.

James Kopaczewski is a Ph.D. student in the Department of History at Temple University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University