City Councils (Philadelphia)

By Andrew Heath

Essay

Since Philadelphia’s founding, a council or—for over a century—councils have been central to the work of municipal government. But the way councils have been chosen, the roles they have performed, and the composition of the people who have served on them have changed markedly since the start of the eighteenth century. From the unrepresentative “closed corporation” of the colonial era, through to the diverse, democratically elected body of the early twenty-first century, councils help to illustrate wider changes in Philadelphia’s past. Their history also offers insights into long-running battles to define the balance between legislative and executive power in local administration.

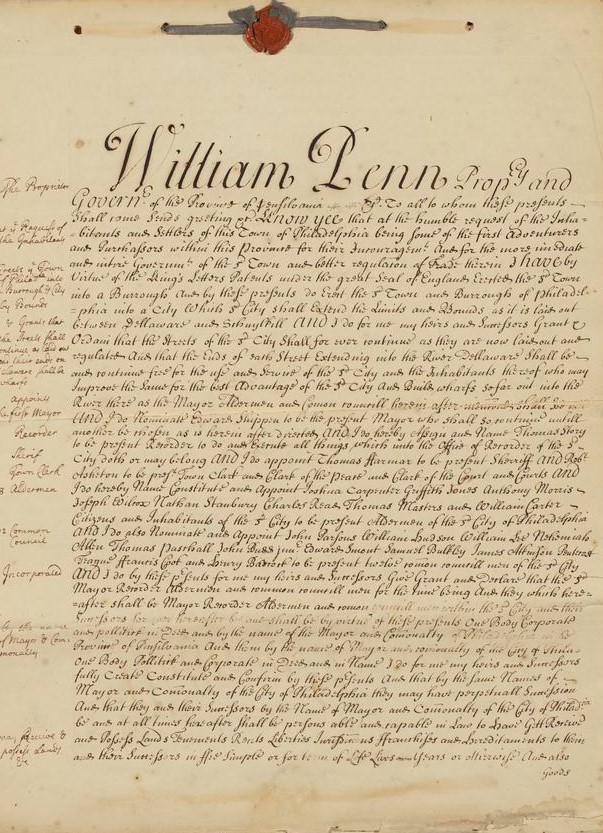

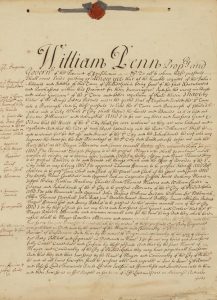

Philadelphia’s colonial council resembled the “closed corporations” of English towns. By the seventeenth century, such places hardly lived up to the ideal of the self-governing city. Some form of council probably met before William Penn (1644-1718) issued his City Charter in 1701, but that document created a body on the English model, with aldermen and councilmen appointed for life. A mayor and recorder joined them on Philadelphia’s city council, which had the power to police its own members and add to its ranks but was subject to no electoral oversight. With the mayor sitting alongside the councilmen, and aldermen serving as justices of the peace, the council mingled legislative, executive, and judicial functions in one corporate body. Public pressure on city government had to be exerted through the likes of petitioning or crowd action rather than via the ballot.

While the colonial city council performed a wide range of responsibilities, it operated in an ad hoc manner. The mayor convened meetings “from time to time,” and though council members delegated executive and legislative business to subcommittees, they had no permanent standing. As Philadelphia grew, though, the importance of its council grew with it, and in the decades before independence the closed corporation regulated city life. It passed ordinances, launched public works, and oversaw markets and wharves.

The American Revolution swept away the colonial city council, and the post-revolutionary City Charter of 1789 brought major changes. The old closed corporation gave way to a municipal government more open to citizens’ influence. Voters now elected councilmen and aldermen, though the latter retained their judicial role. These representatives, chosen at large rather than by ward, initially sat together in one body, which chose the mayor from one of their own. In 1796, however, an act of the Pennsylvania legislature deprived aldermen of their seat in Council and divided the remaining councilmen into two branches. Common councilmen were elected for one-year terms, while the smaller body of Select councilmen served for two years. This bicameral system of councils persisted until just after World War I.

Seeking More-Open Government

Influenced by the constitutional upheavals of the revolutionary years, citizens sought to separate the powers of city government and open its institutions to the people, albeit with mixed success. While the 1796 reform introduced a clear division between legislative and judicial branches of the municipal authorities, councilmen continued to choose the mayor until 1839, when—in the spirit of the Jacksonian era—the state legislature opened the office to the ballots of white male voters. At the same time, however, many of the mayor’s appointive powers transferred to the two branches of council. Thus a measure that seemingly separated executive and legislative powers ended up strengthening the grip of Councils in both. Well before 1839 Councils had created standing committees, chaired by Common or Select councilmen, to oversee the likes of the city’s wharves and waterworks. The development of new or expanded municipal services like gas in the 1830s gave councils considerable control over patronage and provided a platform for politicians to build the “rings” that bedeviled late nineteenth-century reform movements. For many political reformers, indeed, stripping Councils of their executive powers would become a longstanding—if frequently frustrated—ambition.

So too would elevating (as genteel reformers liked to cast it) the social character of councilmen. In the Early Republic, eminent citizens saw service on City Councils as part of their civic duty, which also meant they could steer Philadelphia’s government in a direction that suited them. William M. Meredith (1799-1873), a future U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, served as president of Select Council from 1834 to 1839. As late as the 1840s, the merchant prince Thomas Pym Cope (1768-1854) sat on Select Council. But as the city grew, and Whig, Democratic, and Nativist parties mobilized around election time, Councils’ elite hue began to fade. The story of genteel retreat from Philadelphia’s municipal politics in the Jacksonian era can be overstated, but citizens at the time certainly saw political specialists emerging at the helm.

The next major change in the structure of city government, the Consolidation Act of 1854, sought to reduce Councils’ executive role and augment the social standing of its representatives. Consolidation extended the previously two-square-mile city to encompass the entire county, swallowing up in the process a host of densely populated suburban districts run by elected boards of commissioners. Advocates of consolidation hoped the new city government would vest stronger powers in the mayor and reduce Councils to a purely legislative role. They also anticipated that the vast extent of the enlarged metropolis would attract men of experience to the bicameral councils, which were to be elected from the new city’s twenty-four wards. In practice, neither aim worked as intended. Businessmen did win office, but often used their position to ransack the city treasury (like the builder and contractor John Rice, 1812-80), or had close ties to major corporations (like the Democrat and Pennsylvania Railroad solicitor Theodore Cuyler, 1819-76). Ward representation, meanwhile, gave politicians from ethnic and working-class neighborhoods a strong base. For example, William McMullen (1824-1901), a white supremacist Irish-American Democrat from the old district of Moyamensing, became a longstanding member of Common Council in the new Fourth Ward just below South Street. And though the Consolidation Act gave the mayor control over the police, Councils still had the authority to establish city departments and elect their heads. The managers responsible for many of the city’s executive functions therefore held their positions at the whim of councilmen rather than the mayor. This allowed ambitious councilmen like William S. Stokley (1823-1902) to build a patronage base via oversight of municipal departments.

The Bullitt Bill

The Bullitt Bill, passed by the State Legislature in 1885 and named for its architect John C. Bullitt (1824-1902), marked another attempt to rein in Councils’ executive role. Reformers welcomed a measure that seemed to restore the mayor’s appointive powers, which had been held by the legislative branch of the city government since 1839. But in giving Select Council a veto on mayoral appointments, the Bullitt Bill ensured that councilmen would retain considerable influence in everyday administration. While the measure reduced the number of departments from twenty-five to nine, it did little to arrest the growth in the number of councilmen, who numbered 146 by 1919. Philadelphia’s councils developed a reputation for being venal and unwieldy.

In the Progressive Era, with efficiency the watchword, reformers set out to remake Councils once more. Reversing the precedent set in 1796, a 1919 amendment to the Bullitt Bill replaced the bicameral system with a single body, reduced the number of members to twenty-one, and replaced ward representation with a division based on the city’s eight State Senate districts. The new districts corrected the underrepresentation of growing suburbs like Germantown and West Philadelphia while the shift to four-year terms and $5,000 official salaries reflected the sense that oversight of municipal business required professional attention. To increase transparency, the mayor was required to send a budget to Council, which would then hold hearings in public on the proposals.

Once again, though, the reform failed to deliver on its promise. Members could still wield influence over executive functions. Despite a new Civil Service Commission, Council appointed its members and thus had leverage over personnel decisions. And the mayor also needed approval from Council when appointing heads of city agencies. Meanwhile, despite the city’s shift towards voting Democrat in national elections in the 1930s and a growing vote for Democratic candidates in local races, the eight Council districts tended to elect entirely Republican members. The absence of a substantial opposition bloc in Council was compounded by the tendency of Republican councilors to fight first and foremost for the interests of their districts rather than representing the metropolis as a whole. Despite these problems, proposals for another overhaul of city government stalled in the 1930s and 1940s.

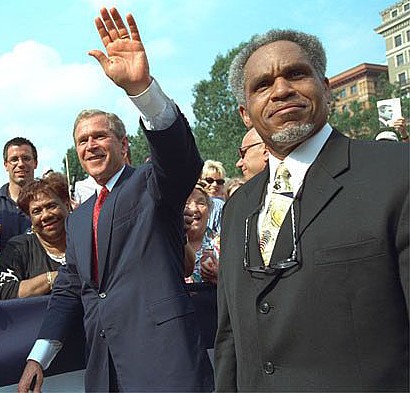

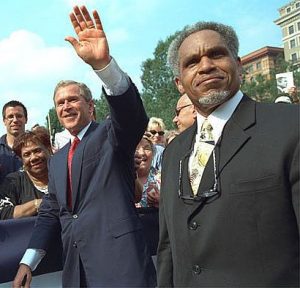

The Home Rule Charter of 1951 aimed to complete the unfinished business of creating a strong mayoralty and reducing Council’s responsibilities. In part, the new charter continued reformers’ longstanding efforts to limit councilors’ capacity to interfere with executive functions. The measure deprived Council of its oversight of the civil service system, its veto over most mayoral appointments, and its capacity to interfere with procurement and construction; the mayor too could veto municipal measures. As one contemporary defender of the new system put it, reformers sought the “centralization of executive authority.” Yet councilors retained some means to check mayoral power. By controlling the finances of city government and through their ability to subpoena witnesses they could keep an eye on the actions of the administrative branch. To enact their agendas, then, mayors had to work closely with Council. Landmark policies like the 2001 Neighborhood Transformation Initiative of John F. Street (b. 1943, mayor, 2000-8) and the 2016 Sugary Drinks Tax of Jim Kenney (b. 1958, mayor, beginning 2016) all required the mayor securing majority support in the Council chamber.

Tweaking the Balance of Power

Home Rule’s architects looked to recalibrate the balance of power in other respects too. The minority party was guaranteed at least two of the seven at large seats in the new Council. As a system of limited voting meant citizens could only pick their favored five candidates for those seven seats, moreover, that minority party also had the option of concentrating their vote share through running a shorter list of nominees. The other ten seats were elected by district. Through this arrangement, it was hoped, the interests of the city would not be drowned out by the claims of each neighborhood.

Despite the strengthening of the mayoralty, the new Council retained the power to regulate land use, which gave it considerable influence over urban development. By custom, the Council delegated decisions over land use and sale of the city’s considerable real estate to the member from the district affected. To its defenders, this practice of “councilmanic prerogative” protected local interests. A councilor, for instance, could block a development in his or her district until community concerns about parking or facilities had been met. To its critics, though, the prerogative slowed the pace of rebuilding and encouraged corrupt bargains between councilors and developers.

With the Home Rule Charter enacted in an era of rapid social change in Philadelphia, the new Council soon looked different from its predecessors. After a century of Republican control, Democrats now dominated, as the coalition of white industrial workers and a growing Black population wielded influence at the polls. The civil rights attorney Raymond Pace Alexander (1897-1974), whose parents had been enslaved in their youth in Virginia, became Philadelphia’s first Black councilor in 1951. That same year, Constance H. Dallas (1902-83) an independent-minded Democrat whose husband was descended from the former mayor and vice president George Mifflin Dallas (1792-1864), served as the first woman in Council. For a century between the 1854 Consolidation Act and the 1951 Home Rule Charter, the city’s councils had offered a path to power for white ethnic politicians. Toward the end of the twentieth century, the strong African American presence on Council underscored the changing demographics of the city and the strength of Black political mobilization. By 2019, however, a mixture of gentrification and frustration with incumbents sometimes left veteran legislators vulnerable in Democratic primaries. Jannie Blackwell (b. 1945), who had represented West Philadelphia’s Third District since 1992, lost in 2019 to Jamie Gauthier (b. 1978), another African American candidate who drew considerable support from young, affluent voters in the precincts around University City.

As in earlier eras, a stint on the post-1951 City Council could serve as a springboard for higher political ambitions. Earlier mayors like William S. Stokley (president of Common Council, 1865-67; president of Select Council, 1868-70) had moved from presidencies of Common or Select Council into the mayor’s office. Late twentieth-century successors like James F. Tate (1910-1983, president of Council, 1955-64) and John F. Street (president of Council, 1992-98) did likewise. Thus, while the 1951 charter placed limits on Council’s power, it gave members themselves a platform, which they could use to build a metropolitan-wide reputation. If a century of reform between the mid-1800s and mid-1900s reduced Council’s executive role, by the early twenty-first century it remained a key player in city politics.

Andrew Heath, who lived in Philadelphia between 2001 and 2008, is a lecturer in American History at the University of Sheffield in the United Kingdom. He is the author of In Union There Is Strength: Philadelphia in an Age of Urban Consolidation (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University