Commercial Museum

Essay

Opened to the public in 1897, the Commercial Museum was the foremost source of international trade knowledge for American manufacturers at the turn of the twentieth century. Located on the western bank of the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia, the museum served as a reference library for merchants, facilitated connections between American export traders and foreign markets, and housed exhibits featuring hundreds of thousands of raw materials and goods from around the world. The rise and fall of the Commercial Museum paralleled Philadelphia’s transition over the twentieth century from a hub of industry and trade to a city with a post-industrial economy.

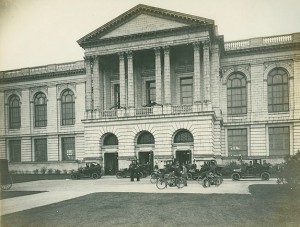

Central to the mission of the Commercial Museum was the notion that commerce was the unifying principle of mankind: past, present, and future. The 1890s marked a period of global transformation, during which the industrial economy of the United States continued to expand. In response to the manufacturing boom, American manufacturers began to seek foreign markets to sell their products. They also exhibited their wares at the world’s fairs that characterized the latter half of the nineteenth century. One of those fairs, the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, had a role in the creation of Philadelphia’s Commercial Museum. Among the many American traders and manufacturers enticed and inspired by the Chicago fair was a former botanist and University of Pennsylvania professor, William P. Wilson (1844-1927). After visiting the Columbian Exposition, Wilson officially founded the Commercial Museum the same year, housing the collections in a variety of temporary locations until the building was officially completed in 1897. Borrowing the neoclassical style of the Columbian Exposition, the Commercial Museum communicated legitimacy through the architectural style of empire, rationality, and intelligence. The Commercial Museum acquired many items from the Columbian Exposition and eventually became the official repository for artifacts from many of the world’s fairs of the era.

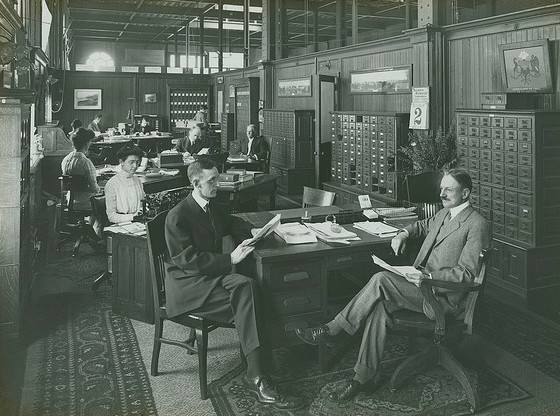

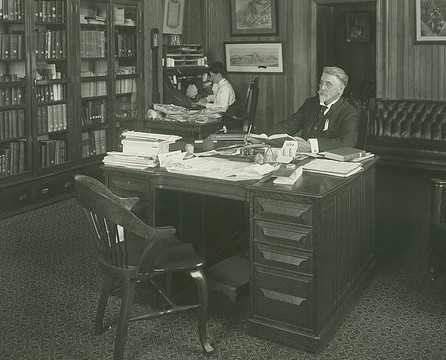

The Commercial Museum aimed to educate everyone about the merits of international trade. Schoolchildren from across the region came to learn about the pivotal role of commerce throughout history and to explore strange artifacts from faraway lands. Merchants came from around the globe to educate themselves about foreign markets and production methods by examining raw and manufactured goods held in the collections. The Commercial Museum also administered a Bureau of Information, which compiled and published international trade and market reports to aid American entrepreneurs as they expanded their enterprises at home and abroad. Inspired by the idea of a commercial museum, American and foreign business leaders in California, France, Berlin, China, and more developed similar museums and hosted world’s fair-style expositions in order to develop transnational trade relations. The museum reigned as the foremost authority on information regarding manufacturing and international commerce in the United States for a quarter century.

The Commercial Museum’s prominence as a beacon of commercial knowledge and exhibits began to wane by the 1920s. A variety of social, political, and economic factors rendered it increasingly irrelevant, the most significant of which was the rise of the International Trade Commission. Developed by the United States Department of Commerce in 1916, the International Trade Commission was closely modeled after the Commercial Museum’s Bureau of Information. Until then the museum acted as the unchallenged provider of international trade intelligence, market reports, and commercial knowledge. The Trade Commission, among other newly formed transnational trade institutions, began to assume this role by publishing international trade and market reports.

By the 1950s the museum had become obsolete. After decades of decreased public interest and visitation, in 1952 the City of Philadelphia restored and attempted to revitalize the Commercial Museum and neighboring Convention Hall. The museum was rebranded as a part of the Philadelphia Civic Center, but its staff was drastically reduced. Thereafter known as the Civic Center Museum, it continued to provide educational programming and display exhibits until 1994, when it closed indefinitely.

In 2001 the City of Philadelphia, through the Orphans’ Court, dispersed the majority of the Commercial Museum’s holdings to universities, museums, and archives around the city. Among these, Temple University’s Anthropology Lab, the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, the Independence Seaport Museum, and the Philadelphia History Museum gained significant collections. The Civic Center and museum building complex were razed in 2005 and became the site for the University of Pennsylvania’s Ruth and Raymond Perelman Center for Advanced Medicine. The Pennsylvania Convention Center, located at Eleventh and Arch Streets, became Philadelphia’s center for commerce and trade, acting as a venue for international trade shows and other events.

Grace Schultz earned an M.A. in History with a concentration in public history from Temple University and is an Archives Technician at the National Archives at Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University