Convention Centers

By Stephen Nepa

Essay

Philadelphia-area residents and visitors have required places for large assemblies since the colonial era, and a variety of temporary and permanent facilities served this purpose in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Modern, multipurpose convention centers appeared in the late 1920s and have since grown in size and scope. By the early twenty-first century, many of the region’s cities, suburbs, and resort towns developed convention centers to attract business, development, and revenue.

In the colonial era, people congregated in public squares, meetinghouses and churches, taverns, and residences. When thousands attended the sermons of evangelist George Whitefield (1714-70) in 1739-40, his admirers erected Philadelphia’s largest building at Fourth and Arch Streets; in 1751, it was purchased by the new College of Philadelphia (later the University of Pennsylvania). In 1774, the First Continental Congress convened in Carpenter’s Hall (built 1770). The State House (later Independence Hall, built beginning in 1732) served the Second Congress and later the Constitutional Convention.

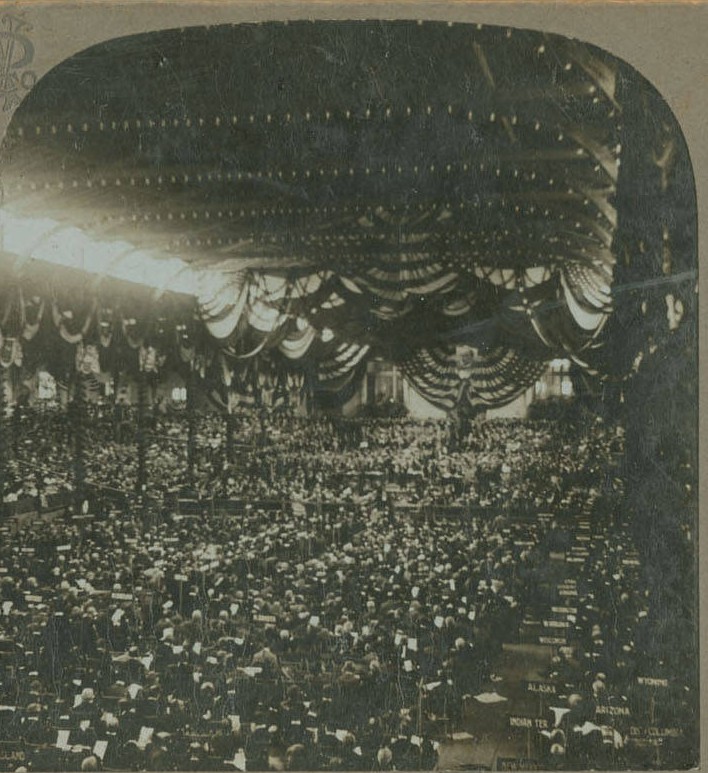

In the nineteenth century, Philadelphia built halls specifically for large meetings, notably Pennsylvania Hall, erected by abolitionists at Sixth and Arch Streets in 1838 but promptly burned down by a violent mob. The city’s churches and performance halls also hosted conventions. The first National Negro Convention met at Bethel Church in 1830. Sansom Street Hall (later demolished) welcomed the 1854 National Women’s Rights Convention. The Philadelphia Museum (or “Chinese Museum,” Ninth and Sansom) hosted the 1848 Whig Party convention. The Republican Party held nominating conventions in Musical Fund Hall in 1856 and the Academy of Music in 1872. When Philadelphia hosted the Centennial Exhibition of 1876, new buildings in Fairmount Park met the need for massive exhibition spaces for goods ranging from art and cuisine to machinery and fashion. Most were temporary, but after the fair Memorial Hall served as Philadelphia’s art museum until 1928, and Horticultural Hall showcased botanical exhibits until it suffered hurricane damage in the 1950s and was later demolished.

Following World War I, as growing industries and trades sought convention venues, the region’s cities invested in modern facilities to capture their business while promoting development and tourism. These emerged in the form of new municipal halls, which hosted both professional conventions and popular entertainment. Atlantic City, one of America’s premier resorts in the 1920s, built Convention Hall on the boardwalk in 1929. With 130-foot ceilings, a 33,000-pipe organ, and seating for nearly 11,000 patrons, the hall hosted not only a variety of trade shows but also America’s first indoor college football game (1940), Air Force training exercises during World War II, the city’s first and only national political convention (the Democratic Party in 1964), a Beatles concert the same year, an indoor helicopter flight in 1971, and most famously from 1940 to 2006, the Miss America pageant (which returned to Atlantic City in 2013 and thereafter). Camden saw its first dedicated convention hall open following WWI. Lost to fire in the early 1950s, its replacement, a former armory, in 1967 hosted a speech by Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) president H. Rap Brown (b. 1943).

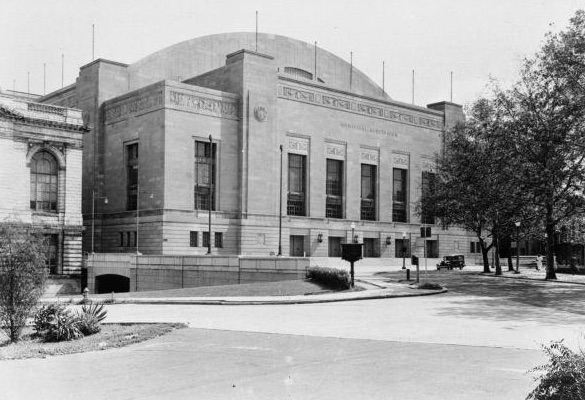

In 1931, two years after Atlantic City debuted its Convention Hall, Philadelphia’s Municipal Hall, designed by Philip H. Johnson (1868-1933), opened on Thirty-Fourth Street near the University of Pennsylvania to “coordinate trade promotion efforts of all kinds.” Complementing buildings used during the 1899 National Export Exhibition, the hall hosted the 1936 Democratic National Convention, at which Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882-1945) received his second nomination, and the 1940 Republican National Convention that nominated Wendell Willkie (1892-1944), who was ultimately defeated.

To further promote Philadelphia’s convention potential, the nonprofit Philadelphia Convention and Visitors Bureau (PCVB) was founded in 1941. New names for Municipal Hall also reflected its increasing importance. In 1948, when the building hosted the presidential nominating conventions for both the Republicans and Democrats, city officials renamed it Philadelphia Convention Hall. In 1952, the facility was renamed the Philadelphia Civic Center and activities expanded to include sporting events, concerts, and appearances by such famous personalities as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (1929-68) in 1965, Pope John Paul II (1920-2005) in 1979, and Nelson Mandela (1918-2013) in 1993. However, after the Spectrum opened as a sports and concert venue in South Philadelphia in 1967, the 15,000-seat Civic Center became obsolete.

By the 1980s, particularly after Philadelphia lost the chance to host the 1984 Democratic National Convention to San Francisco, politicians and business leaders viewed a new, centrally located convention center as essential for the region’s competitiveness and economy. Philadelphia faced increasing suburban competition, as the 100,000-square-foot Valley Forge Convention Center (opened in 1985) profited from small conventions, easy auto access, and proximity to the King of Prussia shopping mall and later the Valley Forge Casino. Officials hoped the envisioned Pennsylvania Convention Center in Center City would spur construction of hotels, restaurants, and retail, while also solving problems of panhandling and homelessness between Broad and Tenth Streets. Nearby residents of Chinatown, already hemmed in by the Gallery shopping mall and fighting extension of the Vine Street Expressway, feared increased crime and congestion. Despite their objections, in 1986 the Pennsylvania General Assembly approved funding for the new facility and in April 1991 construction began on the site just behind the old Reading Railroad Terminal.

Within three months of the start of construction, the PCVB confirmed twenty-three conventions with 160,000 attendees and estimated revenues of $76 million. The $522 million center debuted in 1993, on time and under budget, with then-Vice President Al Gore (b. 1948) cutting the ribbon. Yet parking remained a concern for the center, and the 2000 Republican National Convention met instead at the First Union Center in South Philadelphia. A taxpayer-funded expansion in the 2010s increased the Pennsylvania Convention Center from 435,000 to nearly 1 million square feet, making it the largest convention center on the East Coast. However, bookings dropped due to attendees’ complaints about union labor costs and workers’ intransigence. In spring 2014, Convention Center management banned the Carpenters and Teamsters Local 107 from the facility after the union failed to sign a customer satisfaction agreement. By April 2015, the Convention Center rebounded as nearly thirty new conventions with estimated revenues of $872 million were confirmed.

By the 2000s, convention centers became articles of faith for future growth in a number of U.S. cities. In 2015, the Pennsylvania Convention Center’s competition included not only other convention destinations such as Las Vegas but also regional centers including Atlantic City’s 500,000-square-foot Convention Center, which opened in 1997; Wilmington’s Chase Center (87,000 square feet, est. 1998); the Wildwood, New Jersey, Convention Center (260,000 square feet, est. 2001); and the Greater Philadelphia Expo Center at Oaks in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania (240,000 square feet, est. 2009). Nevertheless, strengthened by hundreds of new hotel rooms and restaurants opened since the mid-1990s, Philadelphia won its bid to host the 2016 Democratic National Convention with the Wells Fargo Center (formerly the CoreStates Center) as the main venue and the Pennsylvania Convention Center hosting the convention’s smaller events.

Over time, Greater Philadelphia’s gathering places and convention centers attracted visitors and generated revenue. Their maturation from intimate spaces and temporary structures to the amenities-rich, multipurpose buildings of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries reflected not only the cultural appeal of cities but also the region’s change from manufacturing to an economy reliant on tourism and hospitality.

Stephen Nepa received his M.A. from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and his Ph.D. from Temple University and has appeared in the Emmy Award-winning documentary series Philadelphia: the Great Experiment. He wrote this essay while an associate historian at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Center for the Humanities at Rutgers University-Camden in 2015. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- After splintering over Convention Center terms, Philly unions divided by picket line (WHYY, September 1, 2014)

- Pa. Convention Center doing brisk business despite union issue (WHYY, November 26, 2014)

- Pa. Labor Relations Board dismisses unions' complaint against Convention Center (WHYY, February 3, 2015)

Links

- Pennsylvania Convention Center

- Philadelphia Convention and Visitors Bureau

- July 14, 1948: Convention Hall's Most Historic Moment (PhillyHistory Blog)

- Teamsters back to work at Pa. Convention Center (Philadelphia Business Journal, June 12, 2015)

- Civic Center Redevelopment (PIDC)

- Teamsters get back into Convention Center (Philadelphia Inquirer, June 13, 2015)

- Convention comeback (Philadelphia Business Journal, July 24, 2015)