Country Clubs

Essay

Country clubs originated in the 1890s as elite, family-oriented havens usually emphasizing golf, but they have never been just about golf or even sports. Clubs fostered sportsmanship, appropriate deportment, and social development while also providing opportunities for exercise. A “golden age” of country clubs lasted until the Great Depression of the 1930s, and the number of clubs grew again in the prosperous decades after World War II and with the continuing suburban boom of the late twentieth century. As clubs proliferated and served a greater variety of members, they reflected the changing culture and economic importance of leisure activities in the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

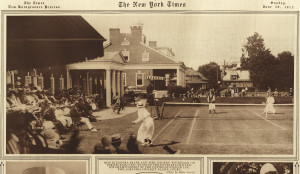

The “country club movement,” as social commentators termed it, began in the 1890s as “golf mania” swept the country. During the economic depression that occurred in the 1890s, many privileged men turned to golf as a less expensive alternative to yachting, polo, and hunting. With suburbanization and an increasing emphasis on leisure, sporting activities also gained popularity among the middle class. Some contemporary writers viewed the desire of women to play sports as the most significant factor in the proliferation of country clubs, which, unlike earlier men’s clubs, were family-oriented.

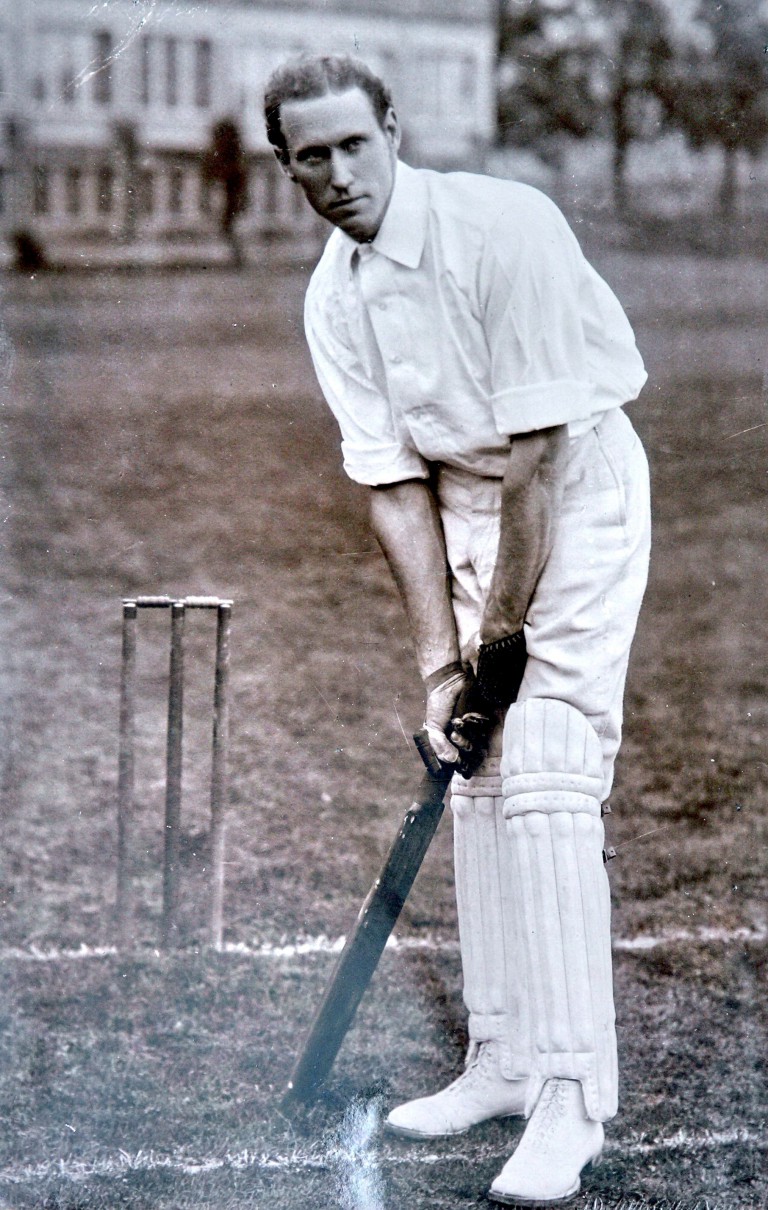

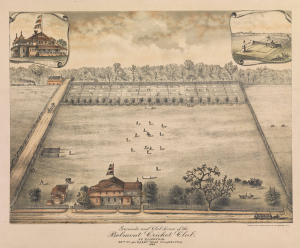

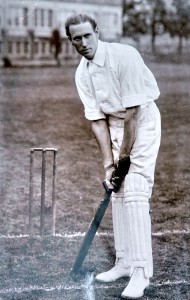

Forerunners of the modern country club included men’s city clubs, union leagues, urban athletic clubs, and resort casinos (clubhouses). In Philadelphia, the big four cricket clubs were the first four country clubs. At one time Philadelphia had as many as one hundred cricket clubs, evidence of the appeal of the sport to all social classes, but members of the Philadelphia (established 1854), Germantown (est. 1864), Merion (est. 1865), and Belmont (1874-1914) cricket clubs enjoyed large clubhouses and spacious lawns. Dining rooms and verandas provided spaces for socializing and for family members to watch matches. The cricket clubs incorporated other sports activities, such as croquet, bowling, and tennis, all played by women as well as men. Members at three of these clubs were also attracted to golf. In 1895, the Philadelphia Cricket Club in Chestnut Hill opened a nine-hole golf course. Golf enthusiasts at the Merion Cricket Club began playing golf the following year and the Aronimink Golf Club (est. 1900), later relocated to Newtown Square, Delaware County, grew out of the Belmont Cricket Club in southwest Philadelphia.

Early Clubs With Golf

Even before members of cricket clubs became golf enthusiasts, several other country clubs included golf. In 1890, socially prominent Philadelphians including John C. Bullitt (1824-1902) and E. T. Stotesbury (1849-1938) founded the first non-cricket-centered country club in the region, the Philadelphia Country Club (est. 1890) on City Avenue. They stressed that members should be able to enjoy “recreation and pleasure without encountering any person or anything which will in the least degree be inconsistent with good behavior or good manners.” Most of the founders were heads of families who desired a conveniently located family club where they, their wives, and children could enjoy respite from the city. Liveried coachmen met trains from Center City to bring members to the club.

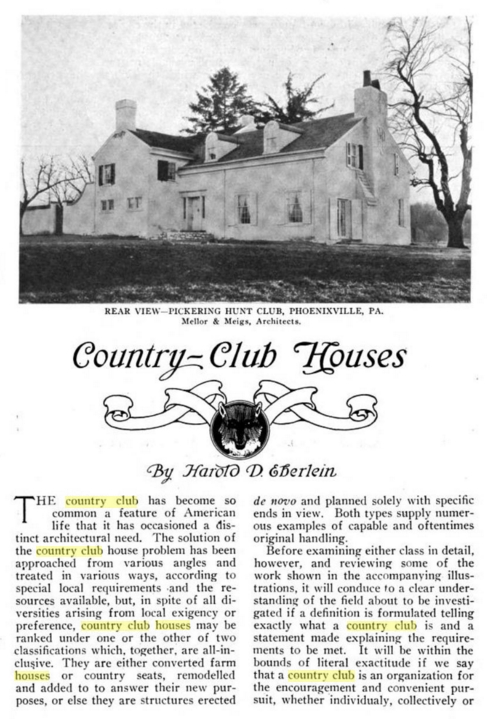

Following the pattern of most early clubs, which leased or purchased country estates or farms and adapted existing residences for new uses, the Philadelphia Country Club purchased “Steinberg,” the former country estate of the Duhring family, located within city limits adjacent to Fairmount Park. Initially a club for riding, driving, and polo, two years after its founding the Philadelphia Country Club added a nine-hole golf course, with two holes on land leased from Fairmount Park. The popularity of golf soon meant the course was insufficient and in 1924 the club purchased property on Spring Mill Road in Gladwyne, which could “be reached by automobile in 30 or 35 minutes from City Hall,” the club announced.

After the founding of the Philadelphia Country Club, the vicinity near City Avenue became the location of several more clubs, including the Bala Golf Club (est. 1893) on Belmont Avenue within the city and the Overbrook Golf Club (est. 1900) just outside the city on property that later became the site of Lankenau Hospital. Scores of new country clubs opened throughout the Philadelphia region in the years surrounding the turn of the twentieth century. The Harper’s Official Golf Guide of 1901 listed about forty clubs in the Philadelphia area. Many affiliated with the Golf Association of Philadelphia (GAP), which in 1897 became the first regional golf association in the country. Over time, member clubs extended from Lancaster to Scranton in Pennsylvania, from Princeton to Cape May in New Jersey, and to New Castle County, Delaware. By 2015, the GAP had 151 member clubs in the region, which also hosted additional nonmember country clubs. Just four weeks after the founding of the GAP, the Women’s Golf Association of Philadelphia became another first of its kind, testifying to the enthusiasm of many women for sporting activities.

Clubs Outside the City

Although many early country clubs were established within the city of Philadelphia, most eventually moved farther from Center City because landowners would not renew leases, adjacent land could not be obtained for extending golf courses, new roads crossed through the courses, or facilities became overcrowded by expanding membership. Relocating outside the city also reflected suburban migration during the twentieth century. For instance, by the time the Philadelphia Country Club sold its Bala property in the 1950s and enhanced its Gladwyne facilities, the majority of members no longer lived in Philadelphia but in surrounding Main Line suburbs.

Country clubs quickly became popular in counties surrounding Philadelphia as more people took up golf, tennis, and swimming and desired more places to socialize. Often, locals introduced to golf while traveling abroad—particularly to France, Britain, and Bermuda—returned to the United States to establish clubs. Eleanor Reed Butler (1871-1945) saw golf played in France and returned home to Media to help organize the Springhaven Country Club (est. 1896), the first club in Delaware County. Women frequently played golf and helped organize clubs, but Springhaven was unique because a woman, Ida Dixon (1854-1916), contributed to the design of the course.

Philadelphians also established clubs in New Jersey. The Burlington County town of Riverton, founded in the 1850s by a group of Philadelphia merchants as a summer retreat, by the end of the century had a growing number of year-round residents who desired to play golf. The Riverton Country Club (est. 1900) became the first in New Jersey to join the Golf Association of Philadelphia. Philadelphians looking for a course offering a better climate for winter golf but tired of taking the train to play at the Country Club of Atlantic City when snow was on the ground in Philadelphia founded the Pine Valley Golf Club (est. 1913) in Camden County, hoping that weather conditions would provide more opportunity for winter play. Some of Philadelphia’s sporting aristocracy, including Connie Mack (1862-1956), became early members. In the first decades of the twenty-first century, the club maintained an elite, all-male membership and a course ranked by some authorities as the best in the world.

Blue Laws vs. Sunday Golf

Social customs and laws sometimes restricted club activities in early years. Blue laws in many states forbade sports on Sundays. In New Jersey, as in other states, though, such restrictions became unpopular and not all communities enforced these laws locally. When members of the Haddon Country Club (est. 1896) in Haddonfield became frustrated with strict local enforcement of blue laws there, a group founded the Tavistock Country Club (est. 1920) in what became the new Borough of Tavistock, which did not intend to enforce a ban on Sunday golf and sports. The Haddon Club folded two years later.

Even before 1920s prohibition of alcohol, some clubs, such as the Riverton Country Club, banned drinking for religious reasons and many others did so to preserve the family atmosphere that made these clubs different from men’s clubs or even many single-sport clubs, such as cricket, polo, or hunt clubs. Membership categories even in the earliest years included both individual and family categories, and some clubs offered junior as well as social-only memberships. Where women could join as members, they typically paid lower entrance or annual fees (and their playing times often were limited to times when working men would not be using the facilities). In return for required fees, country clubs offered variety of sporting facilities; in early years croquet, bowling, archery, billiards, trapshooting, and even basketball and baseball were typical sports played at country clubs. Most added swimming pools, tennis courts, and squash courts for members.

As the social membership categories suggests, country clubs also provided spaces for socializing and entertainment. Theaters, ballrooms, dining rooms, men’s grille rooms, ladies’ parlors and tea rooms, a variety of sitting rooms, porches, and verandas offered ample opportunity for members to socialize and display their mastery of the club’s standards of etiquette.

Varieties of Clubs

Not all golfers liked the “country club atmosphere” of families, swimming pools, and tennis courts. Some organized golf-only clubs, such as the Sunnybrook Golf Club formed in 1914 by six members who left the Philadelphia Cricket Club. Conversely, not all country clubs offered golf. The Philadelphia Aviation Country Club in Blue Bell was founded after the 1927 trans-Atlantic flight by Charles Lindbergh (1902-74), when the idea for a chain of such country clubs across the country briefly engaged aviation enthusiasts. By 2015, only the Philadelphia club survived.

Some country clubs became the focal points of residential communities. In Montgomery County, when the Huntingdon Valley Country Club (est. 1897) moved to Upper Moreland and Abington Townships in the 1920s, the club also intended to subdivide some of the property into lots of two to five acres for members and other “desirable people.” Radley Run in Chester County, built in the 1960s, is a typical mid-century country club community. Residential communities centered on a country club continued to be popular in the early twenty-first century. One newer tract, French Creek Village in Elverson, Chester County, described itself as “the ultimate golf club community.”

While some country clubs remained havens for the elite, a handful crossed class lines to offer leisure activities to blue-collar as well as white-collar workers. The Philadelphia Electric Company baseball field in Upper Darby, Delaware County, became the McCall Field Country Club (est. 1919) when golf became more popular. The DuPont Country Club (est. 1920) in Wilmington, another successor to an earlier employee recreational facility, became a preeminent example of a country club designed to “promote social intercourse” between management and workers. In 1945, the Insurance Company of America reopened the Roxborough Country Club (est. 1925) as the Eagle Lodge Country Club. The Chester Valley Golf Club in Malvern grew out of the Pennsylvania Railroad’s employee country club (est. 1930). This club, along with another company club, the Hercules Country Club (est. 1937) in Wilmington, were the only two in the region founded during the Depression. Men’s fraternal organizations and religious groups also established country clubs that enhanced their collegiality and provided facilities for those excluded from other clubs. A group of Shriners organized the LuLu Temple Country Club (est. 1909), and Catholics dominated Torresdale-Frankford.

Exclusion and Change

Country clubs also formed in response to exclusion. Successful Jewish families, including the Gimbel and Lit families, who migrated to Oak Lane, Elkins Park, and Jenkintown in the early twentieth century established the Philmont Country Club in 1906. In the 1920s, the American Hebrew magazine listed fifty-eight country clubs in the United States owned and operated by Jewish memberships, although most of these excluded the new immigrant generation of Russian Jews. The world of sports, leisure, and social activities of most country and golf clubs remained closed to many. Country clubs reflected the racial and gender attitudes and practices of their early years, but many gradually became more inclusive.

African Americans, who long struggled to gain entrance to country clubs, played golf at public courses. Caddying at country clubs provided an avenue for learning the sport, and some clubs had a specified weekly time for caddies to play the course. This was the case with John Shippen Jr. (1879-1968), an African American/Native American, who served as the Aronimink Golf Club pro for a time in the 1890s. For his first U.S. Open in 1896, the year that the Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson upheld the standard of “separate but equal” for public accommodations, Shippen had to sign up as Native American in order to play.

The 1920s, a decade of explosive growth in the number of country clubs, saw some advances for African Americans. By 1930, middle-class Black golfers had established fourteen golf clubs in the country, including the Fairview Golf Club in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania’s first Black golf club. In the early 1990s, the Professional Golf Association (PGA), which had barred African Americans from membership until 1961, announced that none of its tournaments would be held at country clubs that denied membership on the basis of race, religion or gender. The Aronimink Golf Club could not hold the 1993 PGA Championship because it still had an all-white membership. Since then, formerly all-white clubs such as Aronimink, Merion, and the Philadelphia Cricket Club, among others, recruited more diverse memberships.

Although women were founders and members at many clubs from the beginning, in the early twenty-first century they frequently remained barred from voting, sitting on boards of directors, holding equity interest in clubs, or eating in “men’s grille rooms.” Some clubs continued to ban female membership: In 2015, Pine Valley in New Jersey allowed women to play only at restricted times if accompanied by a male member. The practice of banning golf carts at some clubs also created barriers to access for disabled and elderly players. In other ways, however, some country clubs became forerunners in providing access to physically challenged players, for example by opening courses for outings and tournaments for blind players.

The increasing number of country and golf clubs over the twentieth century paralleled the growing importance of sport, fitness, and leisure in American life, as well as an embrace of suburban rather than urban living. Clubs provided a range of part-time and full-time employment and contributed to the region’s tourist economy by hosting tournaments. By the early decades of the twenty-first century, many more people who desired to belong to such institutions gained entrance. Because of the practice of vetting members and charging entrance and annual fees, however, early claims that country clubs represented an expanding democracy were perhaps overstated.

Anne E. Krulikowski is an Assistant Professor of History at West Chester University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Delaware National Country Club will close at end of year (WHYY, December 1, 2010)

- 8,000 golf balls stolen from two country clubs (WHYY, April 19, 2012)

- Philadelphia Cricket Club looks to upgrade St. Martins campus (WHYY, November 26, 2012)

- Philadelphia Cricket Club wins zoning approval for upgrades at Chestnut Hill campus (WHYY, December 20, 2012)

- Security reviewed for U.S. Open at Merion Golf Club (WHYY, April 17, 2013)

- Merion Golf Club bursting at the seams with fans, media, merchandise (WHYY, June 14, 2013)

Links

- Golf Association of Philadelphia

- The Philadelphia Cricket Club

- C. Christopher Morris Cricket Library and Collection

- PhilaPlace: The Germantown Cricket Club (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Golf Course Designer Albert Warren Tillinghast, 1906 (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- The Wissahickon Country Club's 8th Hole, Known as "The Devil's Own," c. 1910 (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- The CC Morris Cricket Library and United States Cricket Museum: Philadelphia's Hidden Gem