Dogfighting

Essay

The cruel practice of dogfighting has thrived in the shadows of the Philadelphia region for more than 150 years. Most commonly, young men have matched dogs against one another in remote locations and blighted neighborhoods for money and bragging rights. The process of training and culling weak dogs as well as the fights themselves have taken an enormous toll on the animals, frequently leaving them dead or maimed and scarred beyond recovery. Chronic underfunding of law enforcement initiatives, weak laws, and community apathy have long thwarted effective crackdowns on dogfighting’s most brutal practitioners.

Since classical times, people have pitted dogs against other animals in fierce competitions. During the Middle Ages, Europeans engaged in sports known as bearbaiting and bullbaiting in which dogs squared off with these animals in bloody contests. For centuries, few quibbled over the ethics of these savage events because a deeply embedded Christian worldview assured people that the creatures of the Earth existed solely for their own use and pleasure.

American colonists harbored similar attitudes for a time, but eventually bourgeoisie sensibilities prevailed and the respectable classes came to frown upon staged fights between animals. The 1682 Great Law of Pennsylvania banned “Such rude and Riotus Sports & practices as Prized or Stage Plays Masks Revells Bulbaits Cock fightings,” under penalty of ten days hard labor or a fine of twenty shillings. Lawmakers intended such proscriptions to save human souls more than animal bodies, but Quakers also denounced cruelty to animals as a transgression in its own right.

A Turn to the Tawdry

By the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, dogfighting became associated with the more sordid elements of urban life. Middle-class reformers routinely linked blood sports with other iniquitous behaviors and the lower class. In Philadelphia in 1835, the Public Ledger observed, “We never heard of a bull baiting, a dogfight, a cockfight, a boxing match, or a horse race without supplementary quarrels … and we ascribe them to the excitement of the lower animal propensities by the exhibition, as well as to the alcohol always drank on such occasions.” In the view of reformers, such events highlighted a lack of self-restraint and an alarming tendency toward brutality in society.

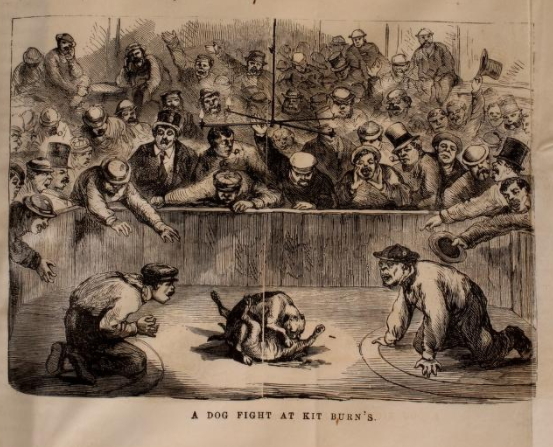

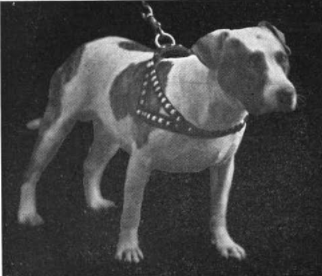

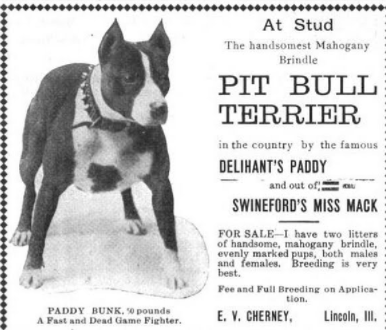

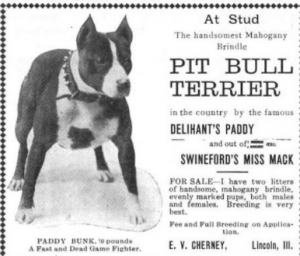

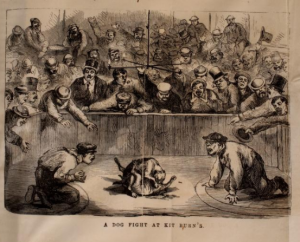

With bulls and bears becoming scarce in urban centers, sporting men bred dogs to fight against one another in locations sequestered from public view. Pit bulls—crossed between terriers and bulldogs— were bred for ferocity and agility for fighting in pits or rings. One of Philadelphia’s more infamous Gilded Age sporting men, Pat Carroll, invested long hours in a dog’s training, sometimes walking it twenty miles a day, throwing it in water to swim, or harassing it with the skin of a rabbit attached to a pole. Matches could last for hours until one dog killed the other or until one or both combatants were too injured to continue. Carroll observed that “a fighting dog does not last long,” noting that tenure in the pit seldom extended beyond four years.

Following the Civil War, dogfighting reached its zenith in the shady underworld of American cities, but the cause of animal rights also gained momentum. The Pennsylvania Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (PSPCA) formed in 1867 and the Women’s Branch (WSPCA) formed the following year. Both of these organizations employed officers with law enforcement powers. In 1869, Pennsylvania enacted an animal cruelty statute that explicitly prohibited the practice of dogfighting under a penalty of ten to twenty dollars for a first offense. New Jersey followed suit in 1873. Anti-cruelty officers routinely raided suspected pits, arrested participants, and confiscated dogs. In June 1874, for example, one such raid nabbed sixty-one men, including Pat Carroll. In most instances, the small fines imposed rarely served to deter further dogfighting. In spite of numerous arrests, Pat Carroll continued his involvement in the Philadelphia dogfighting scene until at least the 1880s.

“Gambling the Dog”

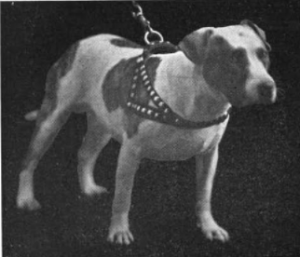

Throughout the twentieth century dogfighting remained on the margins of society, but in the 1980s, the sport took a new turn. It became fashionable for youth in Philadelphia to parade pit bulls with spiked collars through the streets. In this new culture, young men “gambled the dog” or waged impromptu fights on street corners and schoolyards to gain a measure of respect in the community. These practices proved disastrous for pit bulls, in particular, since their trainers often abandoned them when they did not possess the necessary traits of successful fighting dogs. By the late 1990s, the SPCA in Philadelphia was collecting more than three thousand pit bulls per year.

In 2009, public awareness of dogfighting as a persistent urban problem reached new heights when the Philadelphia Eagles signed quarterback Michael Vick (b. 1980), who had served eighteen months in prison in Virginia after pleading guilty to federal charges stemming from his involvement in a dogfighting ring. While some fans praised the Eagles franchise for giving Vick a second chance, others signed online petitions, surrendered their season tickets, or protested outside the team’s practice facility. In the cities where the Eagles played during the 2009 season, Main Line Animal Rescue of Chester Springs, Pennsylvania, purchased newspaper advertisements offering to donate five bags of dog food to local animal shelters for each time opposing players sacked Vick.

Subsequently, the increased recognition of dogfighting as a crime reinvigorated local vigilance. The PSPCA reported a surge in tips about dogfighting, resulting in an increase in investigations of dog fights from 245 in 2008 to 903 in 2009. The Pennsylvania state legislature also enacted new laws that made it a crime to possess dogfighting paraphernalia and shifted the burden of paying for the care of seized animals to the accused owners. Nationally, dogfighting became a felony in all fifty states. For his part, Vick assumed a role as an advocate for the humane treatment of animals, speaking to school and community groups and lobbying for legislation, including the federal Animal Fighting Spectator Act (2014), which made it a felony to bring minors under the age of sixteen to a dog or cock fight. Although fans remained ambivalent about their quarterback, Vick’s presence contributed to the region’s increased recognition of a dog fighting problem deeply rooted in the city and surrounding area.

Jonathan Hall is an environmental historian, specializing in the history of animals in the nineteenth century. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Montana. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- As ill-used pit bull fights for life, SPCA fights stereotype (WHYY.org, April 12, 2011)

- A campaign against illegal dog fighting is being waged by 5th graders (WHYY.org, May 25, 2011)

- N.J. Assembly panel to take up anti-dog fight bill (WHYY.org, March 14, 2013)

- SPCA, police continue investigation into possible E. Germantown dog-fighting ring [updated] (WHYY.org, March 20, 2013)

- Delaware man sentenced to 7 years for dog fighting (WHYY.org, July 1, 2015)