Doylestown, Pennsylvania

By Bart Everts | County Seat

Essay

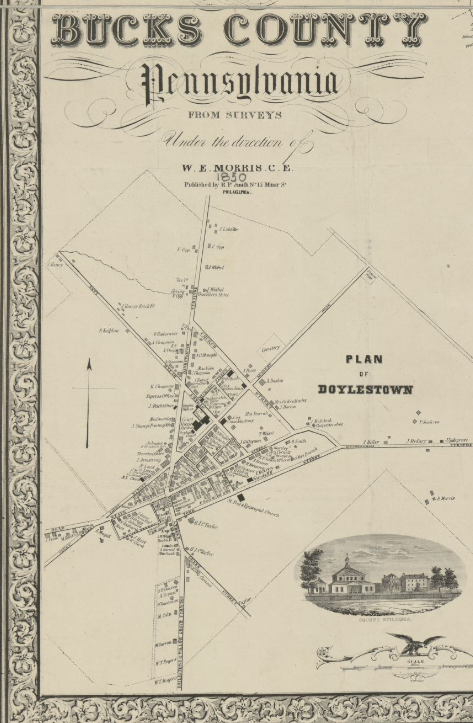

Located a mile north of the Routes 611-202 convergence, thirty-five miles north of Center City Philadelphia, Doylestown has served as the government center of Bucks County for over two centuries. Once a small village surrounded by farms, Doylestown developed into a bustling borough with a thriving downtown, a university, two museums, and commuter rail that carried passengers to Philadelphia in an hour.

Prior to European colonization, the Lenni Lenape Indians lived on the land that later became Doylestown. Ceded by William Penn to the Free Society of Traders in 1682, it was subsequently owned by Jeremiah Langhorne (1672-1742) and Joseph Kirkbride (1662-1736). The borough’s origins traced back to William Doyle (1712-1800), a tavern keeper of Irish ancestry. Doyle’s home sat adjacent to Dyers Mill Road, a north-south route established in 1722, which ran from Philadelphia to Easton (and later became Route 611). In 1730, a new east-west route (later Route 202) was established that ran from Coryell’s Ferry (later New Hope) to Norristown along the Schuylkill River. In response to the increase in traffic at the intersection of these two roads, Doyle opened a tavern that operated from 1746 to 1776, and a commercial and legal hub quickly developed around it.

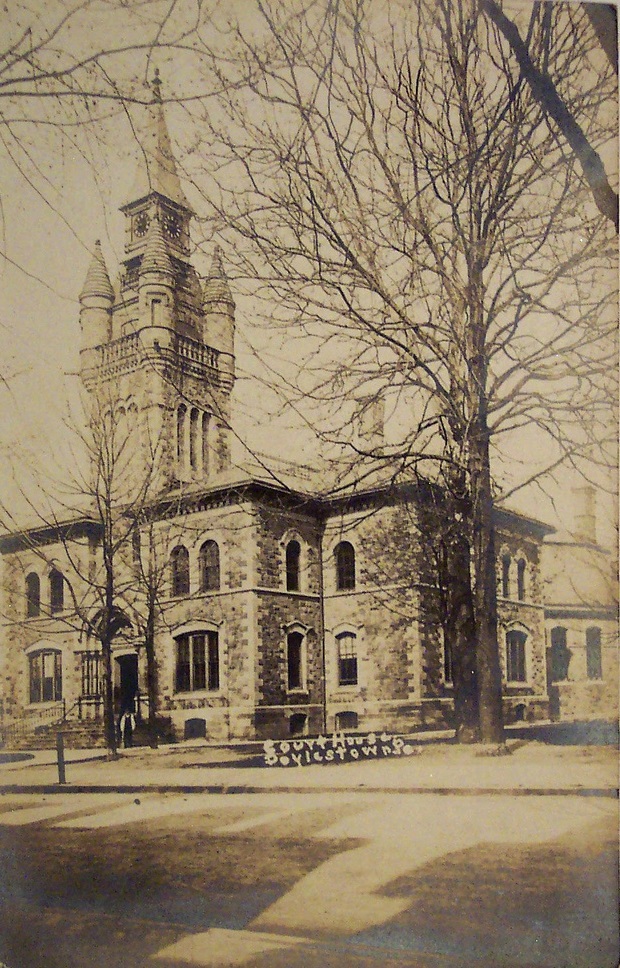

Newtown had been the county seat since 1726, but as northern Bucks County’s population grew over the eighteenth century, county residents seeking a more central location petitioned the Pennsylvania legislature following the Revolutionary War. In 1810, the legislature appointed three commissioners from outside Bucks County to choose a new location for the county seat, stipulating that it could be no more than three miles from Bradshaw’s Corner, the county’s geographic center. In May 1810 the commissioners voted unanimously to make Doylestown the new seat.

Following the American Revolution, a stagecoach was formally established between Philadelphia and Easton, with a stop in Doylestown. The weekly coach charged $2 and was soon joined by a biweekly route from Bethlehem to Philadelphia. Beginning in 1810, when Doylestown became the county seat, local coaches left for Philadelphia every Monday and Thursday (with return trips on Wednesdays and Saturdays). Mail coach lines through Doylestown were established in 1823, and a daily coach to New York began in 1829, with stops in New Hope and New Brunswick, New Jersey.

Rail Services Arrive

Train service arrived in 1856, when the North Pennsylvania Railroad built an offshoot from its primary line stretching from Philadelphia north to Bethlehem. In addition to passenger trains, that branch line also serviced commercial interests, taking milk and other agricultural goods to Philadelphia and bringing industrial goods as well as coal to Doylestown. The Reading Company later took over the North Pennsylvania Railroad, and the Doylestown route was among Reading’s first to be electrified, in 1929. Trolleys also served Doylestown. Initially run by the Bucks County Electric Railway Company and later by the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company, the first trolley line ran twelve miles between Doylestown and Willow Grove, with later lines established in Newtown and Easton.

In 1928, an airport opened as Doylestown Flying Field, later renamed Doylestown Airport. In addition to private planes, in 1946 the Veterans Administration accredited the airport to provide subsidized flight training to former GIs.

In 1897, Joseph Krauskopf (1858-1923) founded the National Farm School. A leading reform rabbi in Philadelphia, Krauskopf had been encouraged by Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910) to build a farming school for Jewish immigrants similar to farm schools in Russia. Krauskopf chose Doylestown as the location for the school because of its proximity to the city, as well as the abundant farmland that surrounded the downtown area. Over the twentieth century, as the school expanded its programs of study, it became Delaware Valley College of Science and Agriculture in 1960 and Delaware Valley University in 2015.

In the 1930s, Doylestown acquired the formerly unincorporated land to the north known as the Doylestown Annex, resulting in a nearly threefold population increase between 1930 and 1940. Lacking a tributary to the Delaware River, Doylestown eluded the growth of commercial factories experienced in New Hope and other towns along the river and remained largely agrarian outside the commercial district. The newly incorporated land consisted primarily of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century dwellings in a residential setting, in contrast to the business district of the borough and outlying farms of the incorporated district.

Postwar Population Boom

In the postwar era, deindustrialization and “white flight” from Philadelphia neighborhoods led to a dramatic increase in population in Bucks County, with the overall county population more than doubling between 1950 and 1960. While lower Bucks County experienced the largest growth in population, Doylestown saw a steady increase as well. Between 1950 and 1980, the population of Doylestown grew from just over five thousand residents to nearly nine thousand, and over two thousand new homes were constructed, primarily in developments outside the downtown area. The growth in the county’s population meant a growth in the central bureaucracy, and in the 1960s, the nineteenth-century courthouse was demolished to make room for an expanded county courthouse and administration building.

Following a national trend, car-centric office, retail, and recreational complexes rapidly replaced main street business districts as the preferred locations for commerce and leisure throughout Bucks County. As a result, the downtown Doylestown business district suffered, and by the early 1960s, many storefronts stood empty. In response, the Bucks County Redevelopment Authority, backed by a federal grant, proposed tearing down twenty-seven historic structures, to be replaced by strip-mall-style complexes as well as parking lots. Among the structures slated for demolition was the Fountain House, a former tavern built by William Doyle.

The plan met resistance from longtime residents, who overwhelmingly rejected tearing down the historic buildings. At a public meeting in June 1964, Doylestown civic leaders organized and presented “Operation ’64,” a plan for restoring dilapidated historic structures and repurposing empty residential structures for retail. With the assistance of low-interest bank loans and assurances that building improvements would not lead to tax increases, the plan called on business and homeowners to improve their facades and landscaping. The project also provided parking incentives such as merchant discount tokens to customers who used parking meters.

Doylestown’s approach to revitalization through restoration drew national praise and produced a moderate increase in sales and foot traffic to the downtown business district over the next decade. Moreover, Operation ’64 ensured that the historic buildings and layout of the business district survived the era of urban renewal. The Doylestown Historic District was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1985.

Doylestown maintained its historic character and pedestrian-friendly business district in the early twenty-first century, and it benefited from the renewed popularity of the downtown business district model. In 2015, a larger justice center complex replaced the court and administration building from 1960. At a cost of over $85 million, the Bucks County Justice Center became the most expensive public project in Bucks County history.

In the two centuries it has served as the county seat, Doylestown saw a steady growth in population, with a spike in the 1930 when it annexed the unincorporated land outside the downtown center. Because of its distance from the Delaware River, Doylestown did not experience the upheaval of industrialization or a crisis of deindustrialization and remained a largely residential community, as it had been since the eighteenth century.

Bart Everts is a reference librarian at the Paul Robeson Library at Rutgers University-Camden and teaches history at Peirce College. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Doylestown Borough, Pennsylvania

- Doylestown Township, Pennsylvania

- The Intelligencer

- Delaware Valley University

- Doylestown Historical Society YouTube Channel

- W.W.H. Davis, History of Doylestown Old and New, Published 1904 (Archive.org)

- National Farm School (Jewish Encyclopedia, 1906)

- Doylestown Agricultural Works (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Doylestown Sanborn Insurance Maps, 1885-1925 (Penn State University Libraries)

- Operation '64: Doylestown's First Renaissance (PDF, Doylestown Borough Bulletin, Spring-Summer 2014)

- Comprehensive Revision Plan for Borough of Doylestown, 1997 (PDF)

- Downtown Doylestown Walking Tour (YouTube)

- Doylestown by Drone (YouTube)