Dream Garden

By Kim Sajet

Essay

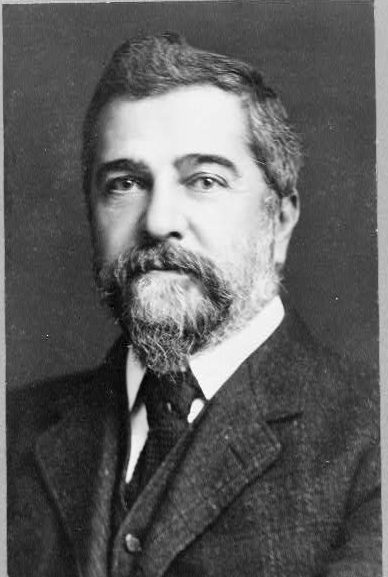

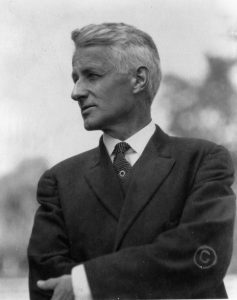

Dream Garden, a glass mosaic designed by Maxfield Parrish (1870–1966) measuring fifteen feet in height and forty-nine feet in length, caused a public sensation twice in Philadelphia’s history. The first time was in 1916 when it was installed in the foyer of the Curtis Publishing Company in Philadelphia, six months after a national debut at the Tiffany Studios in Corona, New York, where over seven thousand admirers had come to marvel at its creation. The second was between 1998 and 2001 when its threatened sale and removal to a casino in Las Vegas led the Philadelphia Historical Commission to designate the work of art as a “historic object,” and the Philadelphia Inquirer to suggest that taking it away was akin to “tearing out the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel for the highest bidder.” With the support of a sustained public protest by preservationists and citizens alike, the Pew Charitable Trust purchased the work of art in-situ and transferred final ownership to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts so that it could benefit future generations.

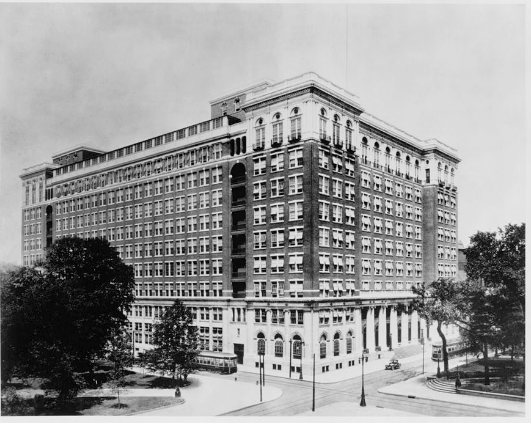

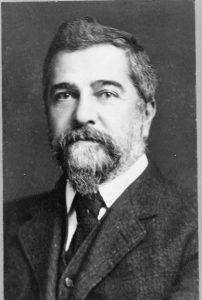

Located in the foyer of the former home of the Curtis Publishing Company at 601–46 Walnut Street (built in 1910), Dream Garden was designed by Parrish, a Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts alumnus, and constructed by the Tiffany Studios in New York. Experts have noted that what makes it so unique—and impossible to remove without damage—is its manufacture. The mosaic is comprised of over one hundred thousand pieces of glass tesserae called “favrile,” a derivation of the Old Saxon word for “handmade.” Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933) believed he had invented a wholly new art form using glass exposed to the fumes of molten metals to develop an iridescent appearance. The mosaic took an estimated thirty craftspeople over a year to blow, cut, and assemble; the traditional method of patterning tiles of uniform size was reinvented in favor of painstakingly hand cutting each piece to approximate the free-flowing brushwork. In some cases, the glass artisans hand-painted the tiles and backed them with gold leaf to add additional shimmer. Under the supervision of artistic director Joseph Briggs (1873–1937), Dream Garden was constructed of twenty-four separate panels and is thought to weigh upwards of seven and a half tons.

Appearing as an idyllic landscape presented behind a faux stone balustrade, Dream Garden apparently resulted from a genuine dream experienced by Parrish. When failing to acknowledge any deeper symbolic meaning to an appreciative public, he noted with irritation: “It doesn’t mean an earthly thing, not even a ghost of an allegory . . . the endeavor is to present a painting which will give pleasure without trying intellect—something beautiful to look upon . . . nothing more.”

Despite his heated denials, however, it is attractive to think that Parrish was both referencing his own perennial garden, located in the Cornish Art Colony in New Hampshire, and paying silent tribute to his New Hampshire neighbor, the renowned American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907). In 1905 Parrish and friends had fêted the ailing Saint-Gaudens with an outdoor play upon a stage resembling a classical temple featuring the same masks in The Dream Garden. The water crashing over huge rocky boulders to the right in the mosaic calls to mind the raw marble Saint-Gaudens used to create his sculptures, while the snow-capped mountains in the background seem to reference Aspet, the ancestral home of Saint-Gaudens at the foot of the Pyrenees Mountains in France.

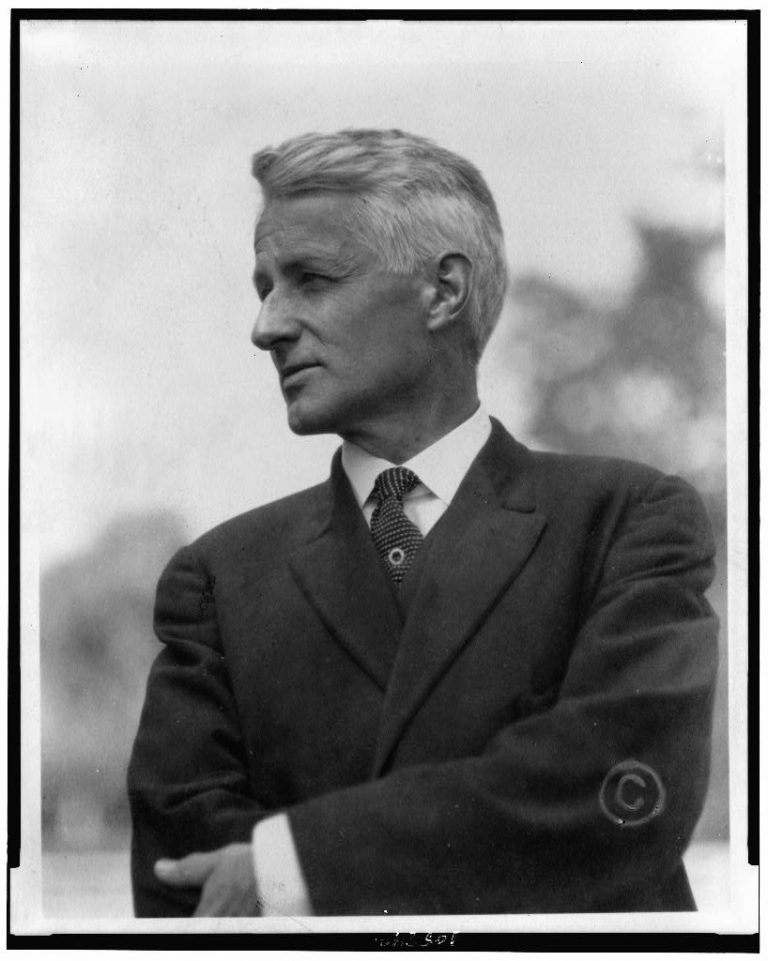

Before critics hailed Dream Garden as a “veritable masterpiece,” however, Edward Bok (1863–1930), the editor of The Ladies Home Journal who had been given the task of finding a monumental work to grace the entrance of his company’s new headquarters, faced a protracted seven-year period of frustration. Bok had initially paid Edwin Austin Abbey (1852–1911) to create a giant painting on the theme of The Grove of Academe, before the artist suddenly died in 1911. This led to a succession of ten artists over a period of four years, two of whom died (Howard Pyle [1853–1911] and Bernard Boutet de Monvel [1881–1949]), two declined to submit ideas (John Singer Sargent [1856–1925] and George de Forest Brush [1855–1941]), and the rest—including Louis Comfort Tiffany himself—submitted designs that Bok rejected. It took a visit to Mexico City and the sight of the magnificent Tiffany curtain for the National Theater in Mexico City to inspire Bok to persuade Parrish to design, and the Tiffany Studios to make, Dream Garden.

The relationship between Parrish and Tiffany, however, was not harmonious. Parrish felt that the 260 colors used in the glass mosaic were not sufficient to lend his design the natural realism he wanted. Blaming Bok for not understanding his aesthetic sensibilities, he refused to attend the unveiling. Tiffany, in a subtle put-down of Parrish’s criticisms, wrote publicly that without his favrile glass it would have been impossible to achieve the desired effect.

In many ways the tensions between Parrish, a classically trained fine artist who nevertheless made a living through commercial illustration, and Louis Comfort Tiffany, the impresario of fashionable décor who wished to be taken seriously as an artist, reflected how aesthetic divisions between art and craft were beginning to wane at the beginning of the twentieth century. Dream Garden is a work of art manufactured at the behest of a businessman to create a moment of mental respite for workers of the machine age in the foyer of a commercial company reliant on advertising. As a patron, Edward Bok was a vocal advocate for the arts and crafts movement and what he termed “domestic architecture, which would provide a new class of urban workers respite from their labors by creating intimate and soothing places of quiet contemplation. Made of glass that could be easily cleaned and suitably ahistorical and apolitical by design, Dream Garden reflected the uneasy coming together of art and industrialization for workers of the Machine Age.

Kim Sajet is director of the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. Prior to joining the Smithsonian, she was president and CEO of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. She has also held leadership positions with the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University