Arts and Crafts Movement

Essay

The Arts and Crafts movement in Greater Philadelphia grew against the backdrop of the area’s increasingly industrial character in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The 1876 Centennial Exhibition brought attention to Philadelphia’s prominence as a manufacturing center and fostered a renewed sense of pride in the city’s connections to national history, but it also elevated anxieties about the state of America’s crafts and the potential shortcomings of mechanized production. In the face of mounting unease with the social and environmental impacts of industrialization, Arts and Crafts advocates sought to mobilize architecture and the decorative arts in the service of recovering what they saw as the disappearing premodern values of craftsmanship, artistic harmony, and cultural cohesion.

The movement spread to the Philadelphia area over the last quarter of the nineteenth century with the increasing reach of the English design reform movement. The influential and polemical writings of English architect A.W.N. Pugin (1812–52), art critic John Ruskin (1819–1900), and especially designer William Morris (1834–96) together called for artists and craftspeople to work toward social and aesthetic reform. With an ethos of honest labor and “truth to materials,” they argued that objects and spaces should be simultaneously beautiful, functional, and produced in conditions that acknowledged the humanity of their makers. These ideas circulated in Philadelphia with the formation of art guilds modeled after those in England, popular periodicals such as The Ladies’ Home Journal (established 1883 in the city), and vibrant personal exchange among artists and designers on both sides of the Atlantic.

By the time of the Centennial, several Philadelphia designers were already promoting aesthetic visions rooted in romantic notions of medieval Europe, rejecting what they considered the formality and ostentation of the neoclassical styles dominating the profession. Architect Frank Furness (1839–1912) and cabinetmaker Daniel Pabst (1826–1910), generally considered “Victorian” figures, nevertheless drew upon the ideas of their English contemporaries, design reformers Owen Jones (1809–74) and Christopher Dresser (1834–1904)—Dresser had attended the Centennial and lectured in Philadelphia—in their emphasis on stylized, organic ornamental schemes. Around the same time, architect Wilson Eyre Jr. (1858–1944) was instrumental in reviving an English vernacular style in and around Philadelphia. These designers laid important groundwork for the area’s later Arts and Crafts activity.

Additionally, young institutions such as the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art (founded 1876, later separated into what would become the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the University of the Arts), the Philadelphia School of Design for Women (1848, later Moore College of Art and Design), or Trenton, New Jersey’s School for Industrial Art (1898, later part of Thomas Edison State College) were modeled after European precedents and attempted to address perceived low standards of design in manufacturing. Through instruction, exhibitions, and lectures by prominent artistic figures, these organizations became important vehicles for the theories of design reform, advancing the notion of craftsmanship in relation to modern manufacturing.

Arts Colonies and Craft Production

Outside of these official institutional efforts, one of the most ambitious undertakings of Arts and Crafts advocates was the establishment of utopian communities to promote aesthetic excellence and social unity through the crafts. Often framed as political acts and conceived in broadly anti-capitalist terms, they attempted to provide solutions to the uneven economic opportunity of the American Gilded Age. These communities drew upon design reformers’ cultural critiques—especially Morris’s views on art and labor—while their picturesque, vernacular-styled physical environments were inspired by the work of reformist architects such as Eyre.

The Philadelphia area was host to a particular concentration of arts-focused community experiments. Most prominent among them was Rose Valley, established near Moylan, Pennsylvania, in 1901. With the production of “artistic handicraft” as one of its core charters, the Rose Valley Association built its arts colony in and around an abandoned textile mill, a potent symbol of disenchantment with mechanized industry. The village was largely the project of Philadelphia architect William Lightfoot Price (1861–1916), whose early career included a stint in Frank Furness’s office, and his partner M. Hawley McLanahan (1865–1929). By 1905, the community included a furniture shop (for which Price designed many of the pieces), metalworking and pottery shops, and a bookbindery in addition to individual artists’ studios. Rose Valley also maintained a “city office” and a press in Philadelphia, which sold and promoted work from the shops. However, their production ultimately proved financially unsustainable, and the Rose Valley Association was disbanded by 1910.

The year before the founding of Rose Valley, Price helped found another experimental community. Arden, Delaware, just north of Wilmington, was a joint venture between the architect and Philadelphia sculptor Frank Stephens (1859–1935) and was based on the “single-tax” theories of American economist Henry George. Stephens and Price couched George’s radical economic principle in medievalizing terms—what they saw as the democratic, “charming” character of the Middle Ages—and borrowed from the English Garden Cities movement, designing a woodland village with two central greens. While the scale of craft activity in Arden was more modest than at Rose Valley, the village was host to a furniture workshop, a printing shop, and the commercially successful Arden Forge, which operated until 1935. In both colonies, social life was equally integral to the utopian vision; theater, poetry, dancing, and music all played important roles in fostering both community spirit and a holistic approach to artful living.

Philadelphia-Area Artists and the Medieval Ideal

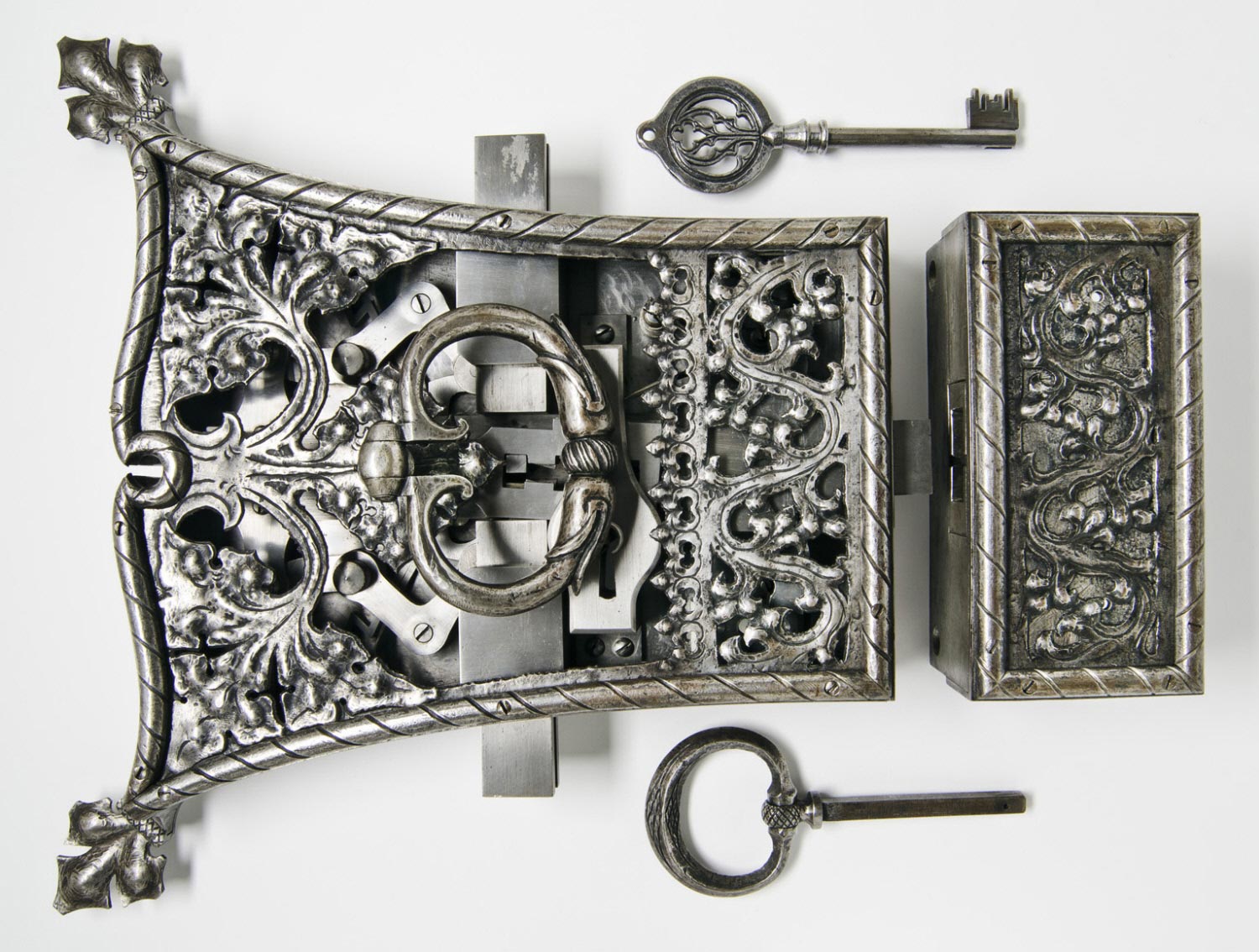

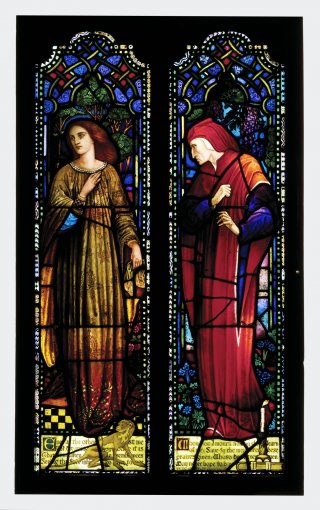

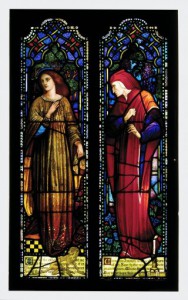

Amid the influence of Philadelphia’s arts institutions and utopian colonies, the work of several individual artists in greater Philadelphia also relates to Arts and Crafts principles, particularly the emphasis on medieval models. The Polish-born master metalworker Samuel Yellin (1885–1940), who studied and later taught at the Pennsylvania Museum School of Industrial Art, used traditional techniques and structured his Philadelphia workshop around longstanding European craft practices. Yellin’s student Parke Edwards (1890–1973) contributed significant metalwork to the Bryn Athyn Cathedral (built 1913–19) in the eponymous Swedenborgian community north of Philadelphia, where workshops established for the building project were consciously shaped after medieval precedent. And amid a prevalent Gothic revival, painter William Willet (1869–1921) formed a stained glass studio in 1898 with his wife Anne Lee Willet (1867–1943). Inspired by the English Pre-Raphaelites, a group with close ties to Arts and Crafts, Willet diverged from the vogue for opalescent glass in the American movement, strongly preferring medieval techniques and materials.

The Pre-Raphaelite influence, as well as involvement of English illustrators such as Walter Crane and Kate Greenaway in design reform, also provided important precedents for some Philadelphia-area graphic artists. Wilmington-based illustrator and author Howard Pyle (1853–1911) published a well-known cycle of Arthurian illustrations (1903–10) that played upon contemporary interest in the Middle Ages. Pyle taught at the then–Drexel Institute of Art, Science, and Industry until 1900, later opening a teaching studio at his own home. His instruction proved so popular that an informal colony of illustrators formed in Wilmington. A number of his students, including Violet Oakley (1874–1961), a Philadelphia illustrator, designer of stained glass and mosaics, and muralist for the Pennsylvania State Capitol), and the painters and illustrators Maxfield Parrish (1870–1966) and N. C. Wyeth (1882–1945) went on to prestigious careers.

In Doylestown, Pennsylvania, Henry Chapman Mercer (1856–1930) founded the Moravian Pottery and Tile Works in 1899. Building on his prolific career as an archaeologist, historian, and collector, Mercer’s initial ambition was to revive disappearing Germanic pottery techniques from early America. However, he also drew significant inspiration from the Middle Ages for the Moravian ceramics, whether in conventional shapes, pictorial “mosaic” tiles, or the distinctive high-relief designs (known as “brocade” tiles) he used in larger narrative compositions. In addition to his membership in the influential Boston Society of Arts and Crafts, Mercer was well-connected with nearby Arts and Crafts advocates. William L. Price, for example, used Moravian tiles in several of his buildings, including Jacob Reed’s Sons’ store in downtown Philadelphia (1903) and the façades of Rose Valley houses. Mercer’s lectures and writings further illustrated his conviction that learning from the past was critical for the arts of the industrial era.

Decorative Arts Farther Afield

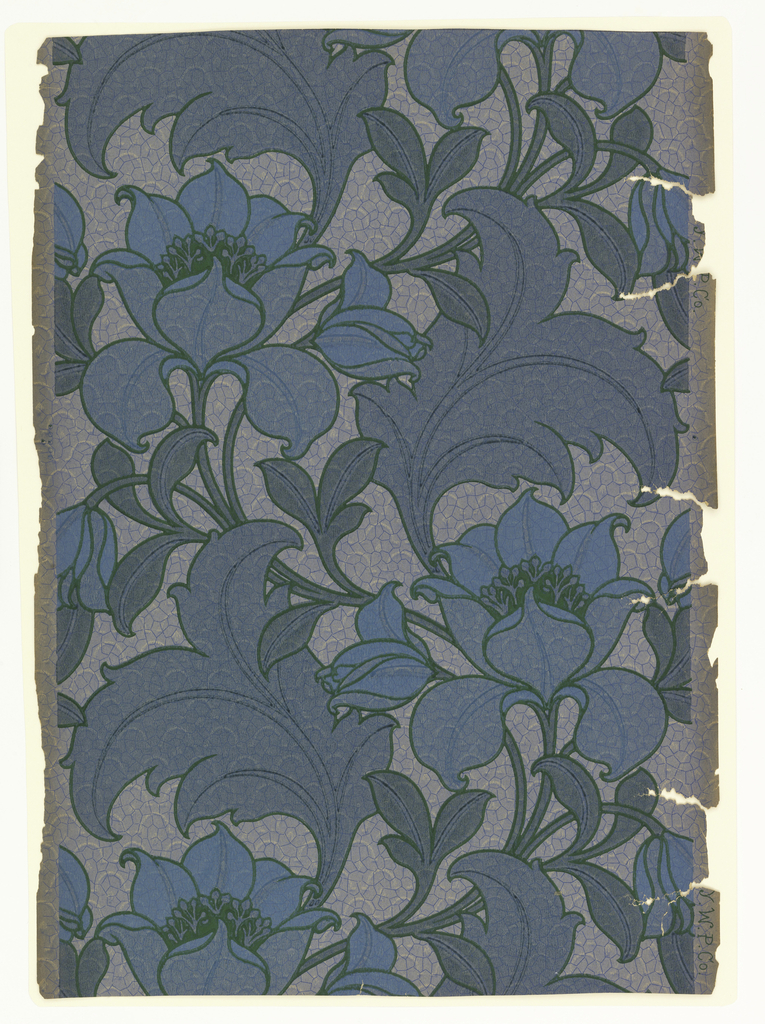

Beyond Philadelphia, a number of commercial firms responded to the growing American taste for the Arts and Crafts, although these tend to be less well-documented. One of the most successful was the Fulper Pottery in Flemington, New Jersey, which had operated since the early nineteenth century but released a popular “Vasekraft” line of art pottery by 1909; Trenton-based Lenox’s Ceramic Art Company (founded 1889; from 1906, Lenox Incorporated) likewise produced Arts and Crafts wares. In southern Pennsylvania, the York Wall Paper Company offered several designs that echoed William Morris’s well-known wallpapers and textiles, while glass firms such as Gillinder and Sons in Philadelphia and the Dorflinger Glass Company in White Mills, Pennsylvania, produced works with organic ornament that would have fit well within an Arts and Crafts interior.

By the time the United States entered World War I in 1917, the American Arts and Crafts ideals were subsiding in the face of shifting tastes, the disbandment of arts colonies, and the increasing economic pressures of industrial production. Some individual firms and makers nevertheless continued their craft-derived work; Samuel Yellin continued forging iron into the 1930s. Ultimately, Greater Philadelphia’s Arts and Crafts history is especially notable for the close-knit nature of the artistic community and the generally high quality of its output. In many ways, Pennsylvanian reformers came as close as any Americans did to realizing the medievalizing ideals of Ruskin and Morris, albeit in short-lived fashion. The Arts and Crafts legacy, furthermore, set an important stage for the rise of the studio craft movement in postwar Philadelphia.

Colin Fanning is Curatorial Fellow in the Department of European Decorative Arts and Sculpture at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. He holds an M.A. in Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture from the Bard Graduate Center. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History