Flour Milling

Essay

At the time the first European colonists settled in the Delaware Valley, few places in the world were as well-suited to the cultivation of grains. The region’s generous rainfall, mild climate, and rich limestone soils provided the perfect environment for planting wheat, the most desirable and profitable grain in the world. By 1750 the Delaware Valley produced such a surplus that its wheat and flour not only supplied the American market but also were exported to Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean. In the process American millers spearheaded innovations in transportation and food safety and established an industrial foundation for the region’s later reputation as the “Workshop of the World.”

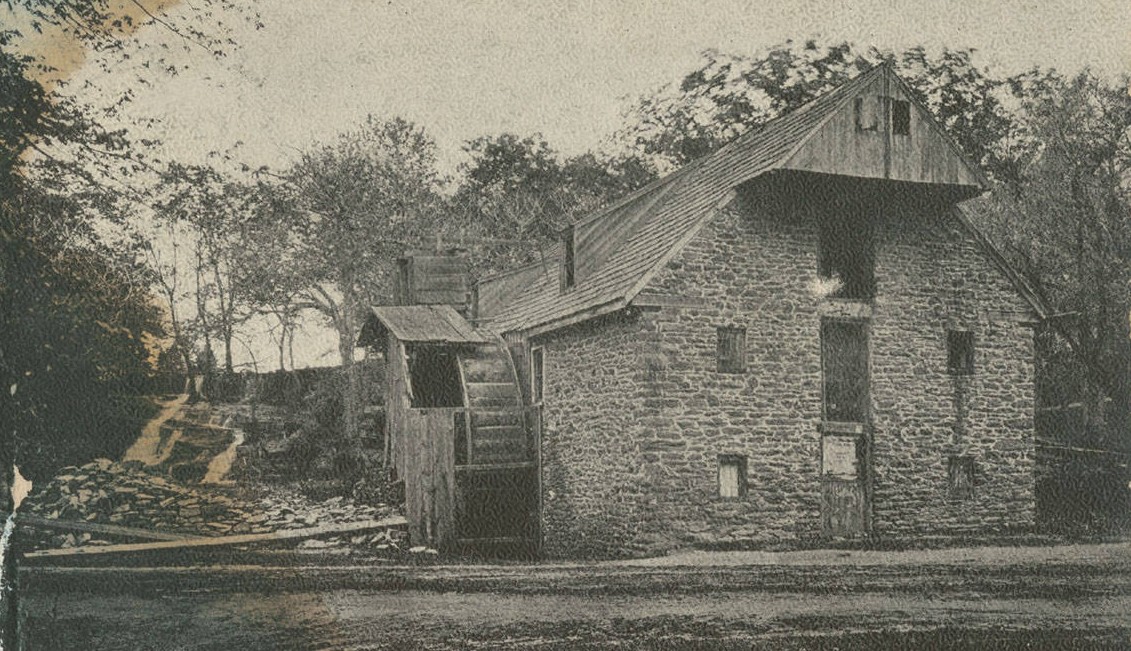

As early as the 1650s, industrious farmers produced enough wheat not only to sustain themselves but also to send a surplus to market. For farmers in the city’s hinterland, the center of any rural community was the “custom” grist mill. More than just a place where farmers took their product for grinding, the mill was where they learned news, met with friends, and transacted business. These custom mills serviced a geographic radius of five to ten miles—the distance a farmer could travel with a wagon in one day. Custom mills were small, typically one or two stories, and the miller extracted payment by taking a “toll,” or a portion of the product. This he could keep for his own use or sell. Unlike the grist mills of New England and the South, most Delaware Valley mills were powered by indoor water wheels, an innovation unique to this area. Moving the wheel inside helped prevent it from icing in the winter, and the miller could work nearly year-round.

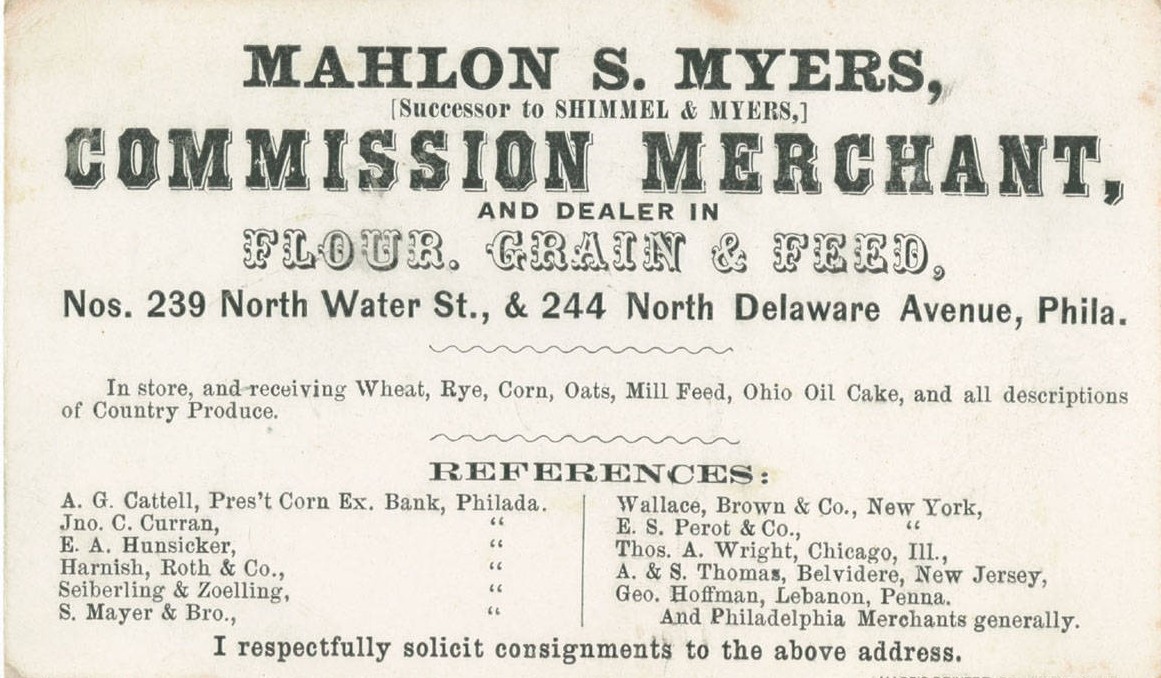

As demand for Pennsylvania flour increased, larger merchant mills appeared. Merchant mills differed from custom mills in that they purchased unprocessed wheat seeds from the farmers and sold the rendered flour at market themselves or through agents. The most famous of these merchant milling centers developed on the banks of the Brandywine River, where shallops (ships slightly smaller than sloops) were loaded directly at the mill with up to two hundred barrels of flour at a time for shipping to Philadelphia. By the 1770s the Brandywine mills featured prominently in travel accounts as “must-see” destinations. Their round-the-clock operation contributed to the growth of a symbiotic industrial town, Brandywine Village, which provided a ready supply of skilled workers such as coopers, millwrights, and ship captains. The difficulty and expense of transporting wheat from western farms to eastern markets, often over roads plagued with potholes and muddy quagmires, led to the incorporation of the first paved turnpikes and turned the simple business of transportation into a potentially lucrative venture.

Flour Inspection Act

The importance of flour to Philadelphia was further demonstrated by the city’s preoccupation with protecting its dominance in the market. After decades of competing with New York and Baltimore, during which time Philadelphia flour developed the reputation of being lower quality than that of its neighbors, the city passed the first comprehensive flour inspection act in 1722. This act stipulated that flour intended for export meet a set standard for quality and be packed in barrels branded with the registered mark of the miller. Millers who improperly classified the quality of their flour or who were caught tampering with weights paid severe penalties. These laws, among the first of their kind in the British colonies, enabled Philadelphia’s flour exports to increase sevenfold from the 1730s to the early 1770s.

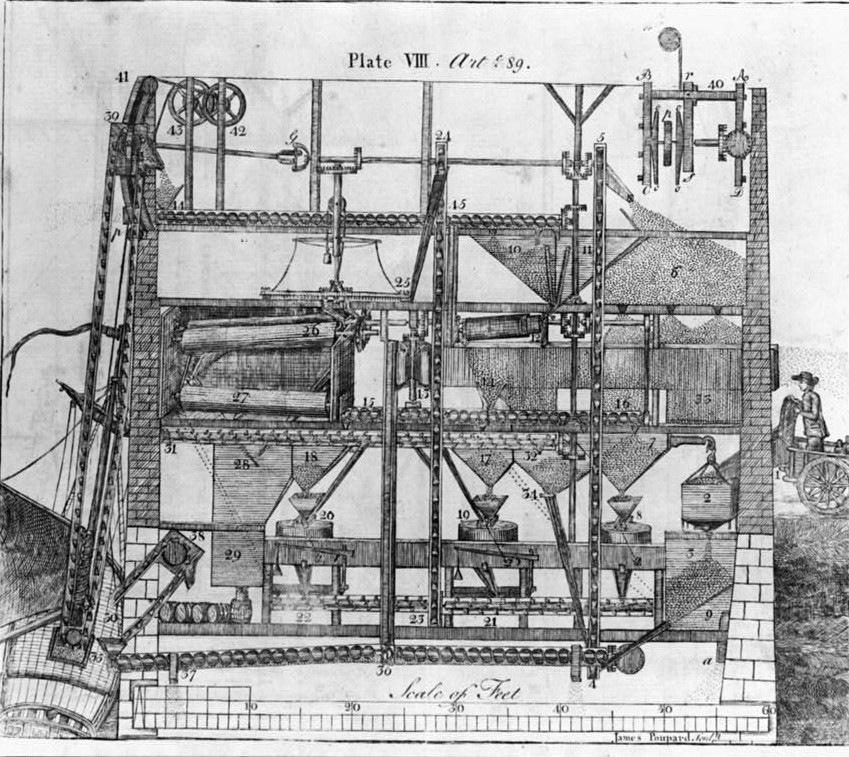

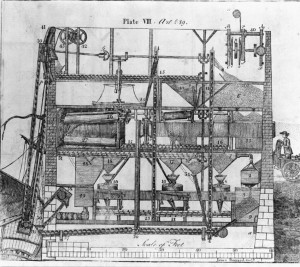

This commitment to quality, paired with a series of poor harvests in Europe, soon made the Delaware Valley the breadbasket of the world. A further boon was the work of inventor Oliver Evans (1755-1819). Evans was born in Newport, near Wilmington, Delaware, already famous for its Brandywine River mills. Prior to his inventions, a grist mill required four or five workmen to keep the machines running smoothly and the wheat and flour flowing. The system often bogged down when it came time to sift the flour, which was warm and moist from the friction of the stones. Moist flour clogged the sifters, and warm flour packed before it cooled could turn rancid before it reached its consumers. Evans invented a system by which bucket elevators did the work of men to carry wheat and flour between the different floors of a mill, and a mechanized rake called a “hopper boy” cooled the flour and delivered it to the sifting machines. These innovations made flour milling perhaps the first automated industry in America, and on December 18, 1790, Evans received the third patent ever awarded by the United States government.

Area Reigned Until 1815

The Delaware Valley continued to reign as the world’s foremost milling center until 1815. The steady decline after that time period can be attributed to a number of factors. First, Philadelphia’s flour merchants depended heavily on the trade of high-quality “superfine” flour to European markets. Improved harvests in Europe in the early part of the nineteenth century diminished demand for American wheat and flour, while at the same time the catastrophic invasion of the Hessian Fly, which first appeared on Long Island in 1777, destroyed wheat harvests in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware. After consecutive years of loss, many farmers stopped planting wheat altogether and focused on corn, rye, and oats, which were fine for domestic use but had no market overseas.

By 1860 railroads made possible the free flow of farmers and commerce to the open, fertile plains of the Midwest. Hard Midwestern wheat, higher in gluten content than softer Eastern wheat, could not be processed on millstones because of its tough hull. When “roller mill” technology emerged to process this desirable product, the giant new commercial mills on the Mississippi River won those sought-after contracts. Millers in the Delaware Valley were slow to refit their machines, and most saw no point in competing with Minneapolis, which after 1880 was simply known as “Mill City,” home to corporations like Pillsbury and Gold Medal Flour.

For a century, Greater Philadelphia served as the powerhouse of the world’s flour economy. Even though the flour bubble burst after 1815, there existed enough of an industrial foundation that many of these mills and commercial centers successfully shifted to more marketable products. The Brandywine Valley’s world-famous grist mills converted to textiles, paper and gunpowder. Emerging industries took advantage of existing pools of skilled laborers and shippers, as well as one of the best transportation infrastructures in the country. All of these were built in large part on the back of the flour industry.

Jennifer L. Green spent four years as the education and interpretation director at a historic grist mill in Chester County, Pa., and continues her work in the industrial history of the Greater Philadelphia area as Program Manager at the National Iron & Steel Heritage Museum in Coatesville, Pa. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2012, Rutgers University