Freemasonry

Essay

Freemasonry, one of the oldest fraternal societies in the world, arrived in America with migrants from England to Philadelphia, Boston, and other places in the British colonies. The fraternity in the Philadelphia area became one of the strongest of all American grand lodges and created one of the finest examples of Masonic architecture in the world, the Philadelphia Masonic Temple. The history of the fraternity has been steeped in mystery and secrecy, but as an organization devoted to faith, love, charity, and Enlightenment values, Freemasonry withstood the ebbs and flows of public opinion to survive as an American institution.

While some mythology traces the origins of Freemasonry to the building of King Solomon’s Temple, the organization likely evolved from the stonecutter guilds of masons that existed in England from the Middle Ages. These “operative masons” gathered in groups to teach their craft and ensure high standards of workmanship and fair trade, similar to later trade unions. By the seventeenth century, these groups of operative masons were transforming and blending into established gentlemen’s clubs that began to discuss the importance of reason in guiding human affairs. Flourishing primarily among the upper-middle and elite classes, these Enlightenment-era societies gathered in “lodges” like their operative predecessors but referred to themselves as “Freemasons” or “speculative masons” to denote the importance of Enlightenment ideals of free will and to refer to operative masons who were “free” to accept wages of a master. Around 1717, four of these lodges formed an administrative body, the Premier Grand Lodge of England, as the first grand lodge. Yet even with deep roots in esoteric ritual, the fraternity maintained strong ties with charity by funding hospitals, scholarships, and relief to the needy.

Although there is some contention, most scholars agree that Freemasonry arrived in America through either Philadelphia or Boston with migrants from England. In 1715, John Moore (1658-1732), Collector of the Port of Philadelphia, made the first known reference to Freemasonry in America when he noted in his diary that he had “spent a few evenings of Masonic festivities with my Masonic Brethren.” A reference to “several Lodges of Freemasons” in Pennsylvania appeared fifteen years later in The Pennsylvania Gazette, published by Benjamin Franklin (1706-90), future grand master of Pennsylvania. In 1730, the Premier Grand Lodge of England appointed Daniel Coxe Jr. (1673-1739), former governor of West Jersey with land holdings in both New Jersey and Pennsylvania, as provincial grand master of New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, thus establishing the first grand lodge in British America, albeit subservient to the “mother [Grand] Lodge” in England.

A Loyalty Crisis

As the American Revolution loomed and the impending split with England gained momentum, Freemasonry in the Philadelphia region and elsewhere in the American colonies faced a loyalty crisis. Leading up to the Revolution, a schism developed between “Ancient” and “Modern” masonic lodges over differences in rituals and membership requirements with the “Moderns” maintaining more elitist views on membership and favoring ties with England over local home rule through the establishment of a stronger Provincial Grand Lodge. Ultimately the Ancients, the newer and more radical branch, won out, forcing lodges that adhered to the Moderns ideology to fold into Ancient lodges. During the Revolution, an informal convention of American Masons from around the colonies met in 1779 at the camp of George Washington (1732-99) and his troops at Morristown, New Jersey. At the meeting the idea of a national grand lodge was proposed by the Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania with Washington intended to serve as the general grand master, but the initiative failed to gain traction.

After the War for Independence, the democratic ideas of the Revolution melded with the egalitarianism of Freemasonry, which flourished throughout the United States. As the premier commercial, social, and political center of the new nation, Philadelphia saw an increase in Masonic activity as membership grew motivated by ideas of civic participation, charity, and fraternity. In each of the new states grand lodges opened new subordinate lodges and membership expanded, especially for the Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania headquartered in Philadelphia. Pennsylvania Masons founded lodges outside of Pennsylvania in eight other states, three U.S. territories, and even outside the United States in two colonies not under British rule. Between 1787 and 1806, grand lodges founded in New Jersey and Delaware took control of the Pennsylvania-founded lodges outside the state. New lodges also formed in Philadelphia and the surrounding area, including several French-speaking lodges founded by émigrés from France and Haiti. In 1797 Prince Hall Masonry, a separate organization based on African American membership, also arrived in Philadelphia and established a lodge.

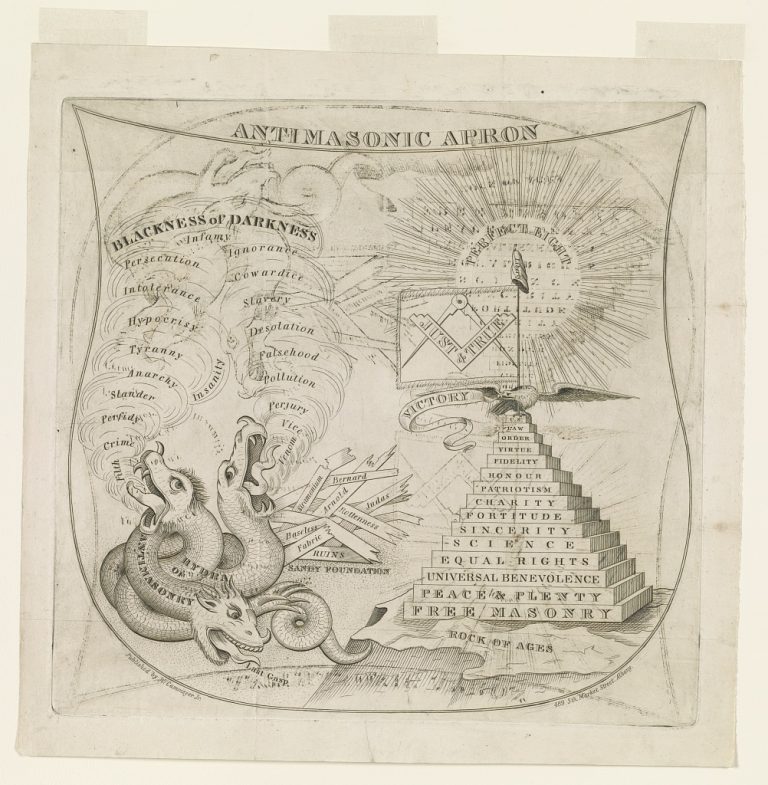

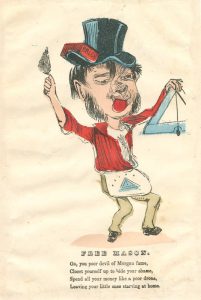

The situation changed, however, when upstate New York member William Morgan (1774-1826) disappeared after announcing his intent to publish the latest of many exposés about the secret society. The fraternity became widely criticized and lost public favor. While earlier the secret meetings and rituals were viewed as mostly harmless activities of a benevolent society, after “the Morgan Affair,” public sentiment turned against the Masons. Exposés and conspiracy theories had abounded since the beginnings of Freemasonry in England, but in the period from 1826 to 1839 they became especially virulent, claiming masonry to be a nondemocratic plot aimed at creating an aristocracy and undermining the American spirit of egalitarianism, morality, and belief in Christianity.

Anti-Masonic Sentiment

Anti-masonic sentiment grew in New York State and in 1828 led to the formation of the Anti-Masonic Party, which spread to Pennsylvania and Vermont two years later and nationally by 1832. Throughout the country, membership declined and many lodges closed or consolidated. While Philadelphia remained a center of Masonic activity in the United States, the group’s large parades and public celebrations that often marked St. John’s Day (a celebration on the feast day of St. John the Evangelist, one of the two St. Johns who serve as the patron saints of Masonry) and other Masonic events shifted to more private affairs. After the Morgan Affair Masonry turned inward, away from the public and toward promoting fraternity among members and shifting to smaller local philanthropic causes within their own communities.

By the mid-nineteenth century, Freemasonry stabilized, and by the end of the century the Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania had the most members of any American grand lodge. Because of Philadelphia’s importance to the region, membership in the subordinate lodges in nearby areas also grew, notably in Camden County, New Jersey, and New Castle County, Delaware.

In 1868, after meeting at numerous locations throughout Philadelphia including the Free Quaker Meeting House, Independence Hall, and two Masonic Halls on Chestnut Street, the Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania dedicated the cornerstone for a new Philadelphia Masonic Temple on Broad Street north of Center Square, the future site of Philadelphia City Hall. Designed by local architect and Mason James H. Windrim (1840-1919) and with the interior designed by Mason George Herzog (1851-1920), the structure completed in 1873 became one of the best examples of Masonic architecture in the world. The Norman-Romanesque temple included seven lodge meeting rooms and several banquet and reception halls and featured works by numerous Masonic sculptors and artists. The building’s Library hall contained the Grand Lodge’s library, founded in 1817, and the Grand Lodge’s museum, founded in 1908 by Mason John Wanamaker (1838-1922), who was devoted to the history of Freemasonry.

By the new millennium Freemasonry had decreased from the grandeur of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries but remained active throughout the greater Philadelphia area with a diverse membership of brothers drawn to the fraternity for reasons including its history, ritual, and opportunity for fellowship. In 2015 the Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania continued as one of the strongest grand lodges in the world with the second-largest membership of 100,000 members in more than four hundred lodges. Worldwide, Masons continued their philanthropic aims into the twenty-first century through affiliated groups (known as appendant bodies) like Shriners International, founded in New York City in 1870 by Walter M. Fleming (1838-1913) and William J. Florence (1831-1891), which supports the Shriners Hospital for Children-Philadelphia, part of a 22-institution network of children’s hospitals. The Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania also created the Masonic Charities of Pennsylvania and raised millions for the Masonic Children’s Home in Lafayette Hill, Pennsylvania, the Masonic Youth Foundation, the Masonic Villages homes for retired masons, and for scholarships, disaster relief, and maintenance of the Masonic Library and Museum. The history of Freemasonry remained intertwined with the history of the Philadelphia region.

Erich M. Huhn earned his B.A. in History and Secondary Education at Rider University and M.A. in History from Seton Hall University. His research focuses on the socioeconomic shifts that occurred in nineteenth and early twentieth century America with a specific focus on New Jersey and the history of Freemasonry. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University