Heating (Home)

Essay

The Delaware Valley’s frosty winters have always required residents to heat their homes for months at a time. At the time of the Philadelphia’s founding, the dense forests in its hinterland offered ample stocks of firewood—the region’s first home heating fuel. Anthracite coal from northeastern Pennsylvania began to supplement wood in the early nineteenth century and eclipsed it by mid-century. Coal reigned supreme for nearly one hundred years, replaced by oil, gas, and electricity only in the middle decades of the twentieth century. As the technological systems used to heat homes evolved, the sources of energy that households in the Philadelphia region used to stay warm changed as well, moving from local, to regional, and finally national fuel markets.

English colonists to the Delaware Valley brought with them a preference for large, open fireplaces, which meant that as settlement expanded, so did the demand for firewood. Although some German colonists preferred burning wood in closed stoves, this had little impact on the region’s home heating markets. As a result, the fires burning in most colonial hearths were incredibly inefficient, as most heat disappeared up the chimney with smoke and soot.

After more than a half century of depleting local firewood stocks, home heating fuel became a scarce commodity. In 1744, Benjamin Franklin (1706–90) published a pamphlet advertising his “Pennsylvanian Fireplace,” which claimed to burn firewood more economically, produce more even heat, and reduce smokiness. Eventually known as the “Franklin Stove,” this cast-iron inset for existing fireplaces achieved few of Franklin’s goals. Improvements by David Rittenhouse (1732–96) in 1784 helped reflect heat into interior rooms, yet the Rittenhouse Stove was expensive and difficult to install. In 1796 the American Philosophical Society sponsored a contest, complete with a sixty-dollar prize, for the best stove design to “benefit the poorer class of people.” Although intended for less-affluent consumers, the contest winners planned to charge ten dollars—a sum far beyond the budgets of poor Philadelphians—for their stove. As fuel scarcities became more acute, the ability to stay warm in Philadelphia’s frosty winters increasingly depended on a household’s income.

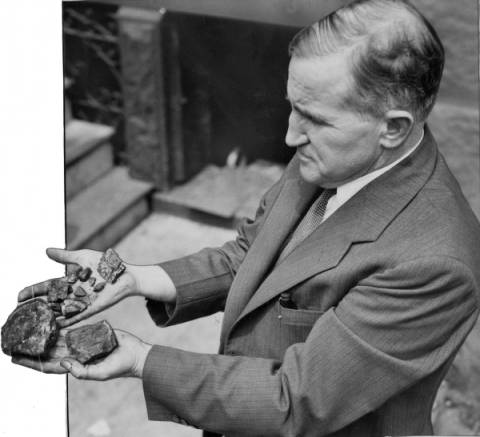

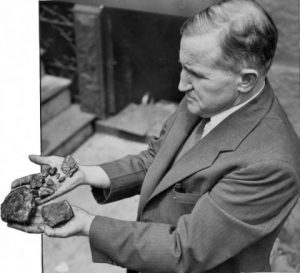

The British blockade during the War of 1812 exacerbated firewood shortages. Jacob Cist (1782–1825) of Wilkes-Barre saw an opportunity and shipped samples of anthracite coal to Philadelphia, along with literature touting its many advantages as a home heating fuel. Although initially Philadelphians struggled to light this “stone coal,” anthracite eventually heated the homes of those willing and able to install a fireplace grate or stove designed for the new fuel. In the 1820s, two new canals, built by the Schuylkill Navigation Company and the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company, connected Philadelphia to the anthracite region and dramatically increased the city’s supply of coal. As late as 1830, though, firewood still accounted for about two-thirds of the home heating market. A concerted effort by the city’s stove manufacturers to provide affordable coal stoves and philanthropic and promotional campaigns that touted anthracite as the “workingman’s fuel” combined to make “stone coal” the preferred home heating fuel by the advent of the Civil War. In fact, by 1860 anthracite met 90 percent of Philadelphia’s home heating demand.

In the post–Civil War decades, a sophisticated network of fuel distribution developed in the region. Most coal arrived via water at the Schuylkill coal wharfs or via railroad at the Reading Railroad’s Port Richmond facility and then was carried by coal dealers to their small yards throughout the city. Dealers competed fiercely for customers, who often complained that they were swindled by unscrupulous dealers. Although retailers offered scales for weighing coal, many consumers doubted their accuracy. Despite calls for inspection and regulation, Philadelphia never provided much oversight of the coal trade, relying upon the market to drive out the worst coal dealers. As the trade had a low barrier to entry—a small coal yard and a delivery wagon—hundreds of coal dealers worked across Philadelphia by 1900. With razor-thin profit margins, the incentive for dealers to cheat customers was significant.

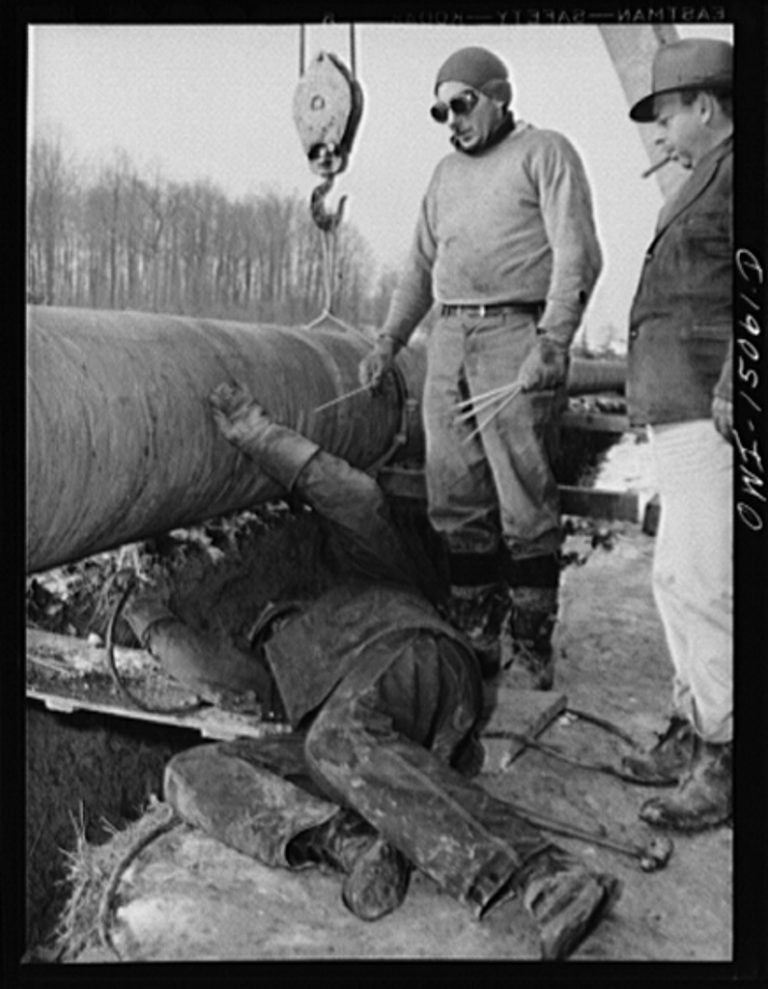

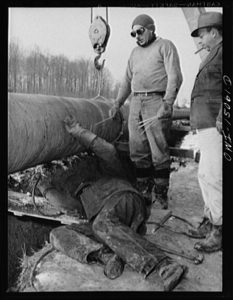

Although coal reigned supreme well into the 1940s, manufactured and natural gas, along with heating oil, eventually replaced mineral fuel in the region’s home heating markets. This meant that area residents were much more likely to manage home heating through a utility company than purchase, manage, and operate their own heating apparatus. In 1924, for example, the Philadelphia Electric Company introduced electrically driven oil furnaces on the market. By 1927 there were over twelve thousand of these furnaces at work in the city. Philadelphia Electric also sold gas furnaces to residential customers. Using heating oil became more cost effective for consumers after the completion of major pipelines, called Big Inch and Little Big Inch, linking petroleum fields in the Southwest with the East Coast during World War II. The expansion of the market for gas—mostly natural gas piped from the Southwest—occurred quite dramatically during the 1940s and 1950s, and by 1955 the utility was adding over ten thousand customers per year. Some local gasworks continued to make “manufactured gas” from anthracite coal, but national trends in energy markets undermined this source of heating fuel. The adaptation of Big Inch and Little Big Inch to transport natural gas to Philadelphia area in the postwar decades, in addition to the construction of new gas pipelines in the 1950s, linked the Delaware Valley’s refineries to national energy flows, as petroleum products from Texas and Oklahoma became cost-effective substitutes for Pennsylvania oil and coal. The rise in oil prices during the 1970s made oil furnaces less attractive, and by the beginning of the twentieth-first century, new methods of drilling for gas, such as hydraulic fracking, increased gas supplies. Still, oil furnaces persisted into the twenty-first century.

No matter what method people in the Philadelphia region used to warm their homes, they found themselves less and less involved in the day-to-day decisions of which fuel to use, how much to purchase, or how to manage their apparatus. Heat became available at the turn of a dial and the original source of that energy was often thousands of miles away. Without the hassle of haggling with dealers, arranging for delivery and storage, and then managing their own furnace, the substitution of gas, oil, and electricity for wood and coal made sense for most households. In the post–World War II decades, for example, Philadelphia Electric alone served one hundred thousand residential natural gas customers, and home heating accounted for two-thirds of the company’s gas revenues. In the end, the convenience of getting heat on demand without worrying about coal prices, shady dealers, or how to operate their furnace outweighed any concerns local consumers might have about the origins of the energy they used to stay warm.

Sean Patrick Adams is Professor of History and Chair at the University of Florida. He is the author or editor of several books, including Home Fires: How Americans Kept Warm in the Nineteenth Century (2014). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- OPEC OIL EMBARGO-1973 (YouTube, June 8, 2008)

- Cooking on a cast iron cook stove, circa 1890 (ExploresPAHistory.com)

- Low-Income Heating Assistance Program (Pennsylvania Department of Human Services)

- Low-Income Home Energy Assistance (New Jersey Department of Community Affairs)

- Home Heating (U.S. Department of Energy)