Insurance

Essay

Insurance is sometimes called an “invisible” element of commerce, but in Philadelphia, it has never been far from view. From the eighteenth century through the twenty-first, Philadelphia’s leadership in the field of insurance has enhanced the city’s preeminence in many types of commercial and communal endeavor. Insurance in Philadelphia, over the years, has meant everything from disability insurance funds managed by immigrants, to “factory mutuals,” through which industrial manufacturers protected one another against the risk of fire, to enormous capitalist ventures in marine and property/casualty insurance. As the business of insurance grew and evolved, it established the city of Philadelphia within global commercial networks, regional zones of economic activity, and statewide legal regimes.

From the eighteenth through the early nineteenth centuries, Philadelphia’s leadership in insurance grew out of the city’s deep involvement in global, national and local projects. Perhaps counter-intuitively, the city’s global ventures began first. The establishment of the first marine insurance brokerage in Philadelphia in 1721 demonstrated that the city had become a significant player in world trade. At a brokerage, a Philadelphia merchant seeking to insure a ship or cargo could fill out a detailed policy. Others, usually fellow merchants, would take on a portion of the voyage’s risk by underwriting it—literally writing their names underneath the policy’s text. If an insured ship was lost or property was damaged in transit, the underwriters paid in proportion to the amount for which they had pledged themselves responsible. If the voyage ended successfully, the underwriters shared the premium that had been paid to the broker for the insurance. The appearance of a reliable group of local underwriters created some financial independence for Philadelphia merchants involved in the global marketplace. Insuring locally meant they would not have to spend months negotiating with overseas insurers or tracking down far-flung underwriters reluctant to pay their shares of a claim.

Insurance brokerages were numerous in Philadelphia by the mid-eighteenth century; the continent’s largest port city had become the principal provider of financial services for the region’s merchants. Brokers clustered together near the wharves, where they thrived on the constant influx of commercial information from ports around the world. For marine insurers, the term “Greater Philadelphia” would have meant very little: commerce and finance linked them far more closely to their peers in London, Bordeaux, and the West Indies than to inhabitants of nearby towns or of Philadelphia’s rural hinterlands. While the exact number of marine insurance brokers in each town in any given year is difficult to assess, the extent of Philadelphia’s regional dominance in insurance is evident in the degree to which its commercial newspapers—in which marine insurers advertised their services—dominated the region. Philadelphia printed its first newspaper in 1719, and the city’s printers competed with one another in ever-greater numbers over the course of the century. In New Jersey and Delaware, by contrast, not a single newspaper was printed before the American Revolution.

Trans-Atlantic Insurance Tradition

In spite of Philadelphia’s prosperity, the city remained a relatively peripheral provider of financial services in the context of Atlantic trade. Even after the Revolution, American merchants generally preferred to acquire insurance in London or other European cities where all kinds of financial transactions were cheaper and more widely available. A real structural transformation in American marine insurance began only after the funding of the debt of the United States in 1790. As Philadelphia became the financial capital of the new republic, enthusiastic investors poured money into public and private projects, including the first marine insurance company in the United States, the Insurance Company of North America (INA). While facilitating Philadelphians’ ocean commerce, INA simultaneously embedded itself in local and national financial networks by investing heavily in the shares of Philadelphia banks and in federal bonds.

The success of INA inspired other speculators to charter corporations along similar lines. While Philadelphia’s marine insurers remained dominant in the mid-Atlantic states, capitalists in smaller towns also took advantage of the wealth generating possibilities of insurance companies. In Trenton and New Brunswick, New Jersey, for example, two new financial corporations received state permission to engage in both the banking and insurance businesses. In this fashion, the new companies were able to spread the risks they took with their invested capital across two intertwined and complementary types of business.

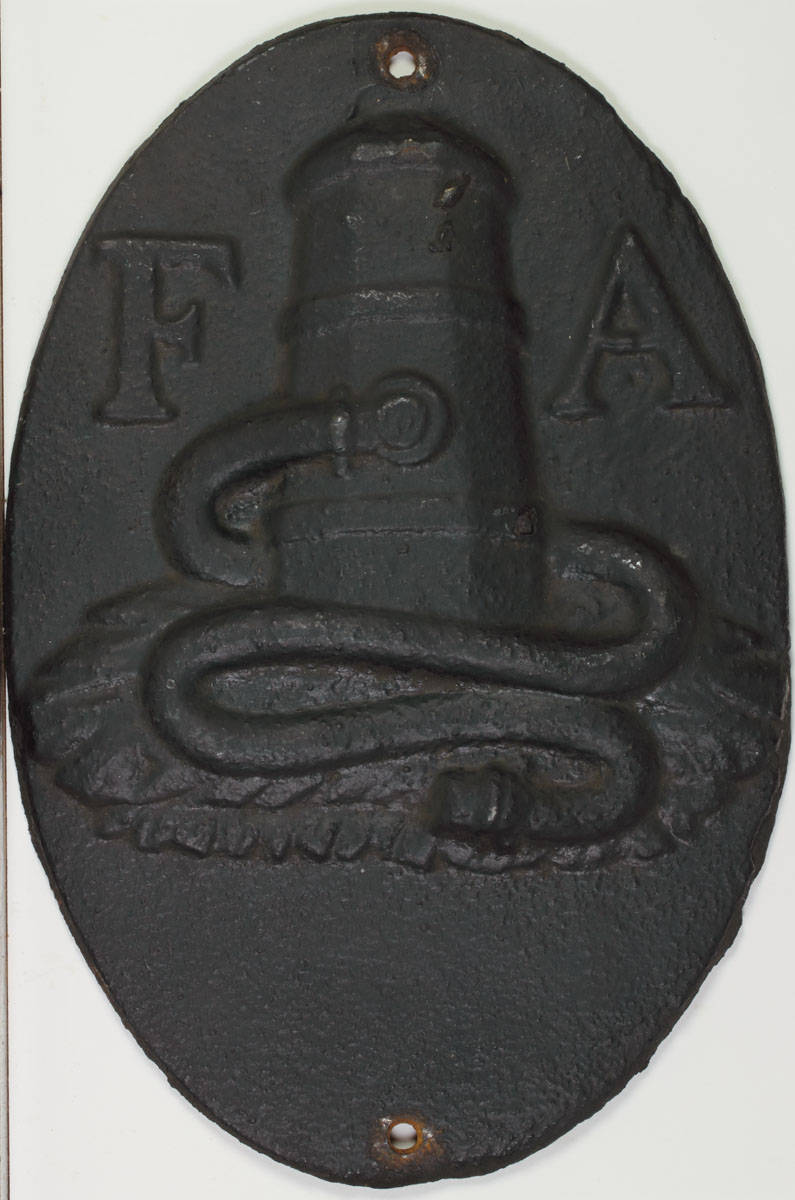

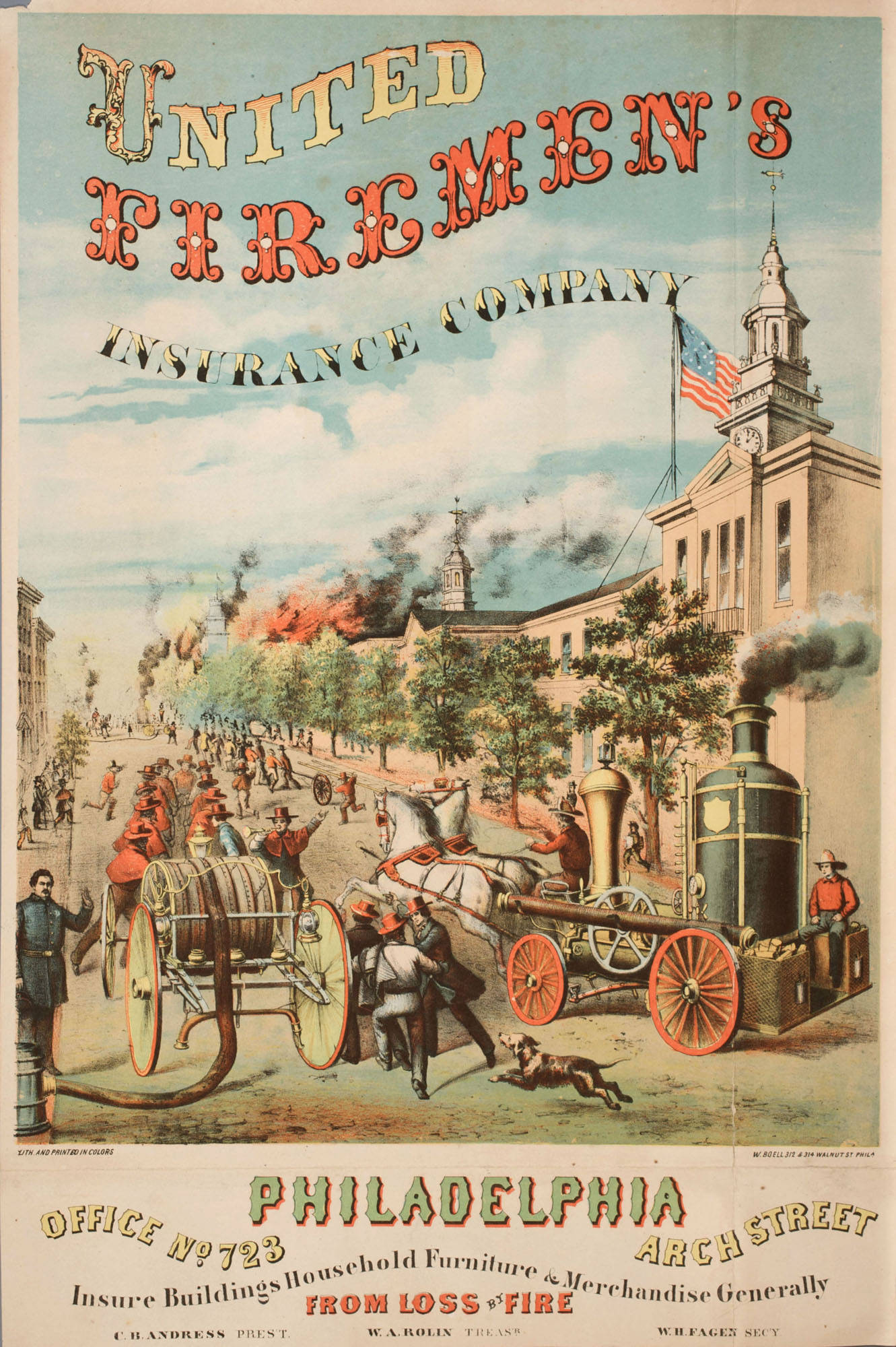

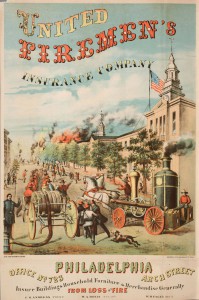

Marine insurance companies enhanced Philadelphians’ ability to engage in commercial transactions spanning continents, but other types of new insurance groups provided them with security at home. Fire insurance associations and mutual aid societies eased the distribution of aid among neighbors in times of personal and communal catastrophe. Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) organized Philadelphia’s first fire insurance society—North America’s second—in 1752. Dues-paying subscribers to the Philadelphia Contributionship and later other companies affixed “fire marks”—usually symbols of peace, amity, or patriotism—to the fronts of their buildings to prove their membership. Fire insurance developed in tandem with organized techniques of fire prevention: members of the Contributionship were required to “keep always in good order … a certain number of leather buckets,” and by 1808, a London visitor noted forty operative fire engines in the city. Inhabitants of cities from Boston to Charleston followed Philadelphia’s lead, creating Contributionship-style societies that benefited subscribers as well as joint-stock companies that sold fire insurance for profit. By 1806, Philadelphia boasted eight chartered insurance companies, which did the majority of their business in marine insurance and a smaller portion in fire. Through active correspondence with insurers in Wilmington and Baltimore, the Philadelphia marine insurance companies were able to bring insurance prices around the mid-Atlantic into closer alignment. And although insurance remained principally an urban—and maritime—commercial practice, the establishment of the Lancaster and Susquehanna Insurance Company in 1807 testified to Philadelphia’s deepening connections with its backcountry.

While fire and marine insurers protected the capital of the city’s property holders, scores of mutual aid societies provided security to Philadelphia’s more vulnerable residents. In 1787, Absalom Jones (1746-1818) and Richard Allen (1760-1831) formed the Free African Society. Members paid one shilling per month, and were eligible to receive three shillings and nine pence per week in times of need. By 1838, Black Philadelphians had founded 119 mutual aid societies with more than seven thousand members. European immigrants began similar projects: Philadelphia’s German immigrants formed at least fifty-six mutual aid societies in the 1830s and 40s. Fraternal orders and tradesmen’s associations also provided crisis insurance to members and their families well into the twentieth century.

Growth of “Factory Mutuals”

As the city grew, the size and concentration of its industrial neighborhoods encouraged manufacturers to join “factory mutuals,” through which they insured themselves against catastrophic losses incurred by factory fires. A group of Rhode Island cotton mill owners created the first factory mutual, and the form rapidly became associated with New England manufacturing, but Philadelphia factory owners also adopted the practice, and it grew apace with the city’s manufacturing over the following century. By the 1930s the amount of factory insurance in force in Pennsylvania was $266 million, second only to the amount in force in New York. New Jersey’s factory insurance, $150 million, was also a substantial portion of the national total.

The hazards of industrialization taught Philadelphia fire insurers the advantages of doing business outside of their immediate neighborhoods. After the Great Fire of New York bankrupted several New York insurance companies in 1835, Philadelphia insurers pioneered the practice of enrolling customers in other cities using full-time remote agents. In the process of hedging their risks, these insurers forged stronger financial links between Philadelphia corporations and inhabitants of other American cities.

Fire insurance companies physically shaped the city of Philadelphia in a number of ways. Their judgments on the safety of different building materials and layouts affected urban architecture, and the detailed maps they generated as surveyors and assessors of urban property became new ways of understanding the city’s built environment.

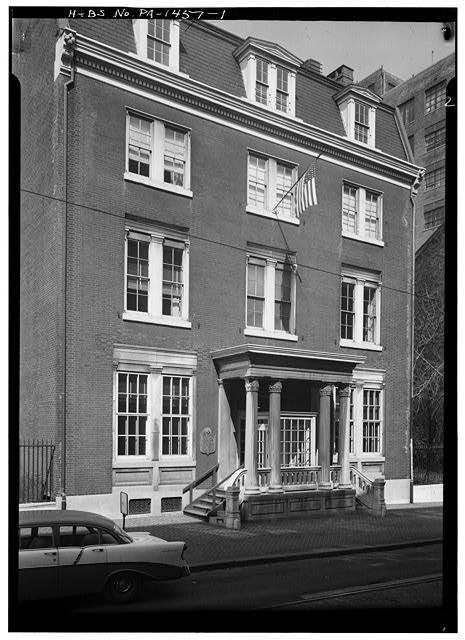

As fire insurance maps demonstrate, the growing scale of insurance in Philadelphia did not simply transform insurance companies into depersonalized vehicles of capital; rather, insurers maintained and even deepened their intimate relationships with urban spaces and their inhabitants. This was as true in the field of life insurance as it was in fire. America’s first life insurance company was founded in Philadelphia in 1809. This company and its imitators targeted the hopes and fears of the emerging middle class. Life insurance was particularly appealing to urban male office workers, who feared their deaths would leave their families indigent, and who appreciated the way insurance companies addressed them as intelligent investors. Enjoying quasi-public status for their roles as caretakers of the potentially indigent, life insurance companies boasted of their own fiscal caution: one nineteenth century business historian wrote that Philadelphia’s American Insurance Company had never undertaken “any spasmodic or reckless efforts to extend its business” and “never lost a dollar by any of its investments.” Imposing life insurance buildings, brick-and-mortar advertisements of corporate stability, became Philadelphia landmarks.

Auto and Health Insurance

The new fields of auto and health insurance emerged very rapidly in the early twentieth century. Both were defined more by state regulations than they were by the demands of port cities. Pennsylvania, a populous state with large numbers of factories and far-flung farms, laid claim to seven percent of the nation’s cars, but was responsible for a full fourteen percent of its traffic deaths. Alarmed by these statistics, state legislators imposed strict regulations on vehicles and drivers in the 1920s, and automobile owners increasingly found auto insurance an appealing option. As most companies in the established lines of insurance hesitated to enter the auto market, new companies were able to grow quickly. The Erie Insurance Exchange, based in the far west of the state, reached $1 million in annual sales by 1946. The success of new corporations such as the Erie Insurance Exchange signaled two important changes in the insurance business. The first was that the wealthy Philadelphia insurance companies of the nineteenth century could not count on retaining their dominance in the twentieth as new lines of insurance emerged. The second was that state laws and regulations were taking an ever-greater role in defining and controlling the practices of insurers; insurance in the twentieth century would be increasingly articulated by state boundaries rather than by global networks of maritime commerce or regional zones of industry.

Health insurance, like auto insurance, was a twentieth century phenomenon shaped by the states rather than metropolitan regions. Across the country, advances in technology and the systematic accreditation of doctors spurred demand for ever-more-costly medical services, and more Americans grew interested in acquiring health insurance. Health insurance projects such as Blue Cross and Blue Shield were promoted by national organizations, and like auto insurers, they were regulated on the state level.

State regulation even made its mark on the old, established lines of insurance. Soon after 1900, many states started setting fire insurance rates directly, while others began supervising rates set by industry associations. Mutual aid societies run by immigrants, voluntary groups, and trade associations peaked after the immigration boom of the early twentieth century, but declined during the Great Depression, superseded by state and federal aid projects. Insurance, in service of nationwide demands and regulated by the states, lost much of its traditional association with ports, immigrant and workers’ groups, and urban industries.

Neighboring States

One consequence of the increased influence of the states on the insurance business was the divergent experiences of corporations situated in neighboring states. Where maritime commerce had once bound Philadelphia insurers closely to those of Baltimore and other port cities, and where nineteenth century industrial activity and immigration had prompted regional cooperation among manufacturers and local cooperation among ethnic groups, state legislatures in each of the mid-Atlantic states took their own courses. Delaware, for example, became a national financial center when it passed a series of laws friendly to the banking and finance industries in 1981. These laws established a new corporate constituency in Wilmington and set that city on a course dramatically different from that of nearby Philadelphia.

Philadelphia maintained its prominence in insurance through education and innovation. The Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania offered the country’s first collegiate-level class on insurance economics in 1904, and in 1941 Wharton partnered with industry leaders to form a foundation for insurance research and education. The Insurance Company of North America revolutionized homeowner’s insurance at mid-century by bundling insurance against fire, theft, flooding, and other hazards into a single “package homeowner’s policy” that quickly became standard.

During the latter half of the twentieth century, corporate mergers transformed some of Philadelphia’s oldest insurance companies. INA, founded in 1792, merged with the Connecticut General Life Insurance Company to form CIGNA in 1982. The resulting entity was purchased by ACE Group, an international company with more than $87 billion in assets, in the 1990s.One might be tempted to conclude that Philadelphian insurers had reached the final stage of their journey into global capitalism, but it is important to recall that Philadelphia insurance companies were worldwide businesses from their very origins. INA, today linked through its corporate successor with offices in Tokyo, London, Zurich, and Santiago, made its name more than two centuries earlier by insuring merchant ventures to Amsterdam, Port au Prince, St. Petersburg and Jakarta. Over nearly three centuries, insurance has forged connections between Philadelphians and their neighbors, their fellow citizens, and their business partners around the world.

Hannah Farber is a Ph. D. candidate at the University of California, Berkeley, completing a dissertation on early American marine insurance in politics and culture. During 2012-13 she held fellowships at the Library Company of Philadelphia and the McNeil Center for Early American Studies. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History