Landfills

Essay

Like many other towns and cities across the United States, municipalities in the Philadelphia region adopted the sanitary landfill as a primary refuse-disposal strategy in the mid- to late twentieth century. Intended to replace open dumps, landfills also promised to serve the disposal needs of a rapidly growing suburban population. From the 1950s to the 1970s many communities in the region constructed landfills for their own use. However, the central city of Philadelphia, which possessed little room for landfills within its bounds, turned to suburban landfill space, raising challenging questions about property rights, state and municipal law, and environmental protection. Landfills quickly became a point of contention between the city of Philadelphia and its rapidly suburbanizing neighbors, especially in New Jersey, making waste disposal one of the toughest policy issues faced by the region in the late twentieth century.

Relative to most large American cities, Philadelphia adopted landfill technology at a late date. By the time sanitary landfilling became prevalent in the Philadelphia region in the early 1960s, the technology was over thirty years old. Originating in the United Kingdom, the sanitary landfill was first introduced in the United States by the city of Fresno, California, in 1937. Sanitary landfilling involves the disposal of refuse either on land or in an open trench or pit. Refuse is dumped in or onto the land and compacted into layers until it reaches a predetermined height, whereupon it is capped with a layer of soil. Sanitary landfills are generally designed to contain or control the spread of “leachate,” or liquid substances released from the landfill over time as a result of decomposition of refuse or the infiltration of rainwater. While some quantity of leachate is inevitable, poor site planning and management can lead to the diffusion of undesirable amounts into adjacent soil, surface water, and groundwater, a situation that can easily become hazardous to human and environmental health if the landfill contains toxic chemicals. These issues were particularly common in early landfills and fueled public debate over their use.

Sanitary landfills developed as a more palatable alternative to open dumping. In Philadelphia open dumps sprang up wherever city officials could find a willing landlord. Lowlands around the Schuylkill River also served as dumping grounds. Informal dumps were often small in size, necessitating an ongoing search for new sites, but some larger sites existed as well, including one at Fourth Street and Oregon Avenue in South Philadelphia that supported a sizable squatter community. As the population of the Philadelphia region grew, open dumping came to be seen as a nuisance that could be minimized though the new technology of the landfill. Counties and municipalities began to open landfills that seemed to promise years of unproblematic disposal.

Two Landfills in 1951

While evidence is scant, as early as 1951 at least two sanitary landfills operated in the region, in Montgomery and Bucks Counties in Pennsylvania. Planning agencies in those counties sought to greatly expand landfill capacity in line with projected population growth. But the going was often slow in the Pennsylvania suburbs; according to a survey by the Delaware County Planning Commission, no sanitary landfills existed in that county as of 1953. At the outset of the postwar period landfills remained virtually nonexistent in New Jersey, although, as in Pennsylvania, planning authorities in localities such as Camden County hoped to introduce the technology in the immediate future. The city of Camden commenced landfilling at a site in the Cramer Hill neighborhood in 1952. In Delaware, where localities more thoroughly embraced the technology, twenty-six landfills opened by 1978, including twelve in northernmost New Castle County.

Ultimately, however, New Jersey became most heavily associated with landfilling, with Gloucester County developing into a major center of activity. Landfilling emerged in South Jersey just as the region entered a period of intensive suburbanization, transforming what had been a largely rural area. For some local farmers, offering vacant land for use as landfill helped to stave off displacement. For example, the owner of the Kramer landfill in Mantua regarded her landfill operation as a “godsend” that allowed her to remain on her farm following the death of her husband. By 1993 the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection and Energy identified 578 “known or suspected” landfills throughout the state, only 37 of which then remained in operation (410 closed prior to 1982, when New Jersey introduced more rigorous closure and remediation standards, and a further 131 closed after 1982).

The spread of landfills in the region provided an outlet for the city of Philadelphia, which adopted landfilling in the post-World War II period to supplement incineration, its primary method of refuse disposal. As mass consumption accelerated and produced greater amounts of inorganic refuse, plastics, and other inorganic packaging materials, the city struggled to repurpose the incinerated remains. By the 1950s Philadelphia’s four incinerators worked overtime, processing larger quantities of waste and producing greater quantities of ash than the city had ever dealt with before. In the early 1960s Philadelphia contracted with private haulers to transport ash from municipal incinerators to several locations in New Jersey, including the Mac Sanitary Landfill and Kinsley Landfill, both in Deptford Township, New Jersey, and the Kramer Landfill in Mantua, New Jersey. Initially, Philadelphia also transported some refuse to landfills in Pennsylvania but encountered stiff resistance from officials in suburban counties.

As Landfills Grew, So Did Suburban Towns

Along with the expansion of landfills in South Jersey, suburban towns also grew as middle-class residents flocked to the area’s new subdivisions. Paradoxically, new residents prized South Jersey’s open space even as their presence often crowded out less-intensive land uses like farming. In 1973 the threat to New Jersey’s open space loomed especially large as Philadelphia officials proposed closing the city’s incinerators in order to meet more-stringent air pollution standards. Landfills would no longer merely supplement incineration—they would replace it. Faced with the imminent arrival of more refuse from Philadelphia, communities adjacent to South Jersey landfills objected. In Deptford, protesters massed at the gates of the Mac and Kinsley Landfills, attempting to prevent trucks laden with Philadelphian refuse from entering. The Deptford protests were part of a larger movement against landfilling that unfolded across New Jersey in the 1970s. Just as Philadelphia prepared to shutter its incinerators, the ire of New Jersey residents bore fruit when the state passed the Waste Control Act of 1973, which banned the disposal of out-of-state refuse.

The City of Philadelphia immediately contested New Jersey’s ban in court. A lengthy appeals process ultimately brought the case to the United States Supreme Court in 1978. In a 7-2 ruling the high court struck down the Waste Control Act as an unconstitutional restriction of interstate commerce. In his dissent to the majority ruling, Justice William Rehnquist (1924-2005) struck a sympathetic chord for New Jersey residents concerned about “extremely serious health and safety problems” posed by landfill leachate.

While the court could strike down New Jersey’s ban, it could not change the fact that years of dumping had filled New Jersey’s landfills. The New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection estimated that all existing landfills in the four New Jersey counties adjacent to Philadelphia would be filled by October 1977. The toxicity of several existing landfills compounded the impending crisis. First to come to light was the Lipari Landfill in Pitman, New Jersey. The Lipari Landfill, which opened in 1958, accepted about 46,000 barrels of waste chemicals over its lifetime, primarily from the Philadelphia chemical firm Rohm and Haas. Although New Jersey closed Lipari in 1971, nearby residents complained of foul odors and expressed fears regarding water quality. The damage wrought by Lipari included increased rates of leukemia and low birth weights, but remediation efforts at the site did not commence until the 1990s.

Fearfulness Over Landfills Grows

The Lipari Landfill was not a repository for municipal waste, but that was of scant comfort to state and local officials contemplating landfill expansion. Trepidation over landfills grew with the appearance of noxious surprises at the Helen Kramer Landfill in Mantua. The Kramer Landfill initially came to the attention of environmental regulators in 1977 when tests on nearby water sources revealed high levels of the metal cadmium. Two years later, complaints arose that the landfill’s owner allowed trucks to empty their contents after the state-mandated closing time. Kramer pleaded ignorance, admitting that she was disengaged from the management of the landfill despite living on the property. State officials succeeded in closing the landfill in 1981, but as with the Lipari Landfill remediation remained years away.

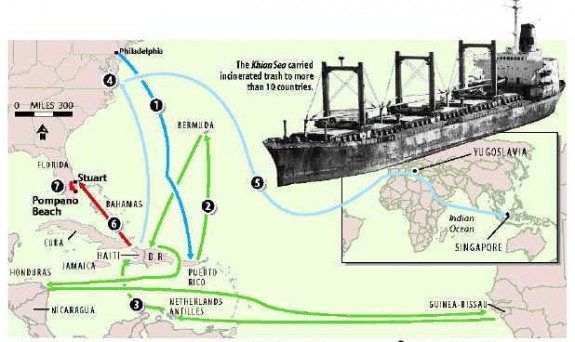

Faced with the impending closure of nearby landfill sites, officials in both Philadelphia and its suburbs began to cast about for alternative waste strategies in the mid-1970s. They were largely unsuccessful. City officials touted novel solutions including the manufacture of paving stones from trash and, the holy grail of municipal waste management, waste-to-energy incineration. However, refuse continued to flow into the city’s old-fashioned incinerators, which remained open despite air pollution concerns. Most of the resultant ash went to one of a dwindling number of landfills (such as the Kinsley Landfill, which remained open in the face of bitter opposition until 1987), but during the 1980s some city contractors made less savory deals to move incinerator ash out of the city. In an infamous 1988 incident, one Philadelphia contractor arranged to ship ash out of the city on a vessel named the Khian Sea, which embarked on a global odyssey in search of a dump site.

Across the Delaware in Camden County a similar effort to create a high-tech waste-to-steam incinerator took shape. The 1984 plan called for building a waste-burning power plant on the waterfront of the city of Camden, thereby lessening pressure on both the area’s landfills and the coffers of the beleaguered city. The proposal deeply divided the Camden’s growth-oriented leaders from the city’s inhabitants, who did not want to bear the costs to health, safety, and dignity of processing waste from wealthier parts of the county. Activist groups such as Citizens Against Trash to Steam (CATS) delayed, but could not prevent, the implementation of the plan; the proposed facility commenced operation in 1991. Plans to build an additional incinerator in Pennsauken, New Jersey, came to naught.

Superfund Sites

In the 1990s remediation efforts began at Gloucester County’s Helen Kramer and Lipari Landfills under the federal “Superfund” law. For years the two sites languished near the top of the Superfund priority list, fueling resistance to the opening of new landfills in the region. By 2015, the Environmental Protection Agency reported the “human exposure status” of both sites to be “under control.” The remediation effort at the Lipari site ultimately resulted in the creation of the Alcyon Park, a general outdoor recreation area, on the former landfill in 1999. Some New Jersey landfills, such Kinsley Landfill, also played a role in alternative energy experiments. In early 2015, utility company PSE&G opened a thirty-five-acre solar-energy farm on the Kinsley site. Meanwhile Camden, whose landfill closed in 1971, commenced restoration of a twenty-four acre portion of the Cramer Hill site in 2009 with the assistance of a $57 million dollar grant to the Salvation Army from the estate of Joan Kroc. The efforts of the Salvation Army and the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection yielded a 120,000 square-foot community center on the erstwhile landfill that opened in 2014. However, in spite of these happy instances of remediation, landfill closure in the Philadelphia region did not eliminate the continuing need for landfill space. It merely ensured that new landfills would be somewhere else. Diminishing space open to landfilling, combined with more rigorous oversight of landfills’ environmental impact, pushed up the cost of landfilling in the region. While landfilling did not cease entirely, Philadelphia’s waste traveled to locations as far flung as Maryland, Ohio, Georgia, and South Carolina.

James Cook-Thajudeen is a Ph.D. candidate in American history at Temple University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Former Deptford landfill could become a major solar farm (WHYY, September 6, 2013)

- Democrats talk sustainability in platform, walk sustainability at convention (WHYY, July 27, 2016)

- Pennsylvania ranks second in landfill trash per capita (WHYY, August 4, 2016)

- Philadelphia making effort to reduce, reuse -- and avoid landfill (NewsWorks, April 18, 2017)

Links

- The Salvation Army Ray and Joan Kroc Corps Community Center Camden

- Two New PSE&G Landfill Solar Farms in Service (PSE&G)

- Solid Waste Management (Encyclopedia Britannica)

- Summary of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (Superfund)- via. the US Environmental Protection Agency

- City of Philadelphia vs. New Jersey (1978) Case Brief (Cornell Law)

- How Landfills Work (Waste Managment via YouTube)