Legionnaires’ Disease

By Dan Royles

Essay

The outbreak of a mysterious pneumonia-like disease in the Philadelphia region in the summer of 1976 puzzled doctors and public health officials. Many of the sick had attended an American Legion convention at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel, giving the new illness the name “Legionnaires’ disease.” Months later, doctors discovered that bacteria in the hotel’s air conditioning system had caused the outbreak. By then, thirty-four of the 221 people who fell ill had died, and the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel had closed its doors for lack of business.

The outbreak occurred during the bicentennial of the Declaration of Independence. After returning home on July 24 from the three-day American Legion meeting in Philadelphia, several of the legionnaires began to fall ill with chest pains, high fevers, and lung congestion. By August 2, twelve had died. Doctors initially suspected that swine flu might be the culprit. If so, it was feared that Philadelphia could become the epicenter of an influenza pandemic, on the order of the 1918 “Spanish” flu that had killed as many as 100 million worldwide. In this light, Pennsylvania state health director Leonard Bachman (b. 1925) considered a quarantine of the city. Bachman held daily press conferences—sometimes twice a day—to update the public on the progress of the epidemic, while the city of Philadelphia set up a hotline to take reports of potential new cases.

Meanwhile, the numbers of sick continued to grow: by August 6, twenty-five had died, with 112 others hospitalized. However, tests for known viruses, bacteria, and fungi that might cause similar symptoms all came back negative. Moreover, the disease showed no evidence of secondary infection; that is, the sick did not seem to pass the illness to those with whom they came into contact. There would be no deadly pandemic, but the question remained: what was killing the legionnaires?

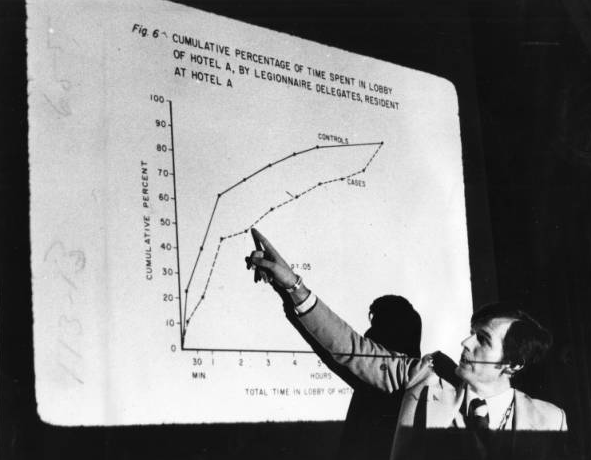

To find out, a team of local and state health officials distributed a survey to the ten thousand people—legionnaires and their families—who had attended the meeting. Through computer analysis of their responses, epidemiologists determined that the sick had all been inside the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel, although some had stayed elsewhere. Moreover, several attendees of the International Eucharistic Conference, which took place at the hotel shortly after the American Legion Meeting, also became ill with the same mysterious pneumonia. On August 14, epidemiologists added presence at the Bellevue-Stratford to the case definition of the new disease.

In the absence of a clear infectious agent, doctors turned their attention to chemical toxins. The symptoms of infection roughly matched those of nickel poisoning, and some speculated that the sick might have inhaled nickel carbonyl, perhaps through fumes from burning business papers. Researchers also tested the pesticides and cleaning products used in the hotel, looking for any clue as to what might have caused the mysterious outbreak. Although answers remained elusive, the number of new cases of “legion disease” dropped off. By the end of August, officials announced that the epidemic had ended. Nevertheless, business at the Bellevue-Stratford declined precipitously. The hotel’s rate of occupancy dropped from 80 percent to 3 percent at its lowest point, while the once-bustling restaurant, bar, and coffee shop were all nearly deserted. In November, the hotel’s owners announced that the Bellevue-Stratford would have to close its doors. (It reopened in 1979, after a major renovation, under new management.)

In January 1977, researchers finally pinpointed the source of the legionnaires’ pneumonia. It was not, after all, poisoning from nickel carbonyl or some other industrial poison, but a bacterium from a previously unknown genus, subsequently named Legionella after the first recognized outbreak. Researchers thereafter realized that Legionella bacteria thrive in large central air conditioning systems, such as that used by the Bellevue-Stratford. They also concluded that similar outbreaks had occurred going back to 1965 in hospitals and large office buildings but had escaped detection at the time. However, the names of both the disease and the bacteria remained linked to the initial outbreak in Philadelphia. A 2002 outbreak of the disease at a Jewish nursing home in suburban Horsham, Pennsylvania, killed two residents and sickened seven others, as well as an employee. In 2005, two attendees of the Pennsylvania American Legion convention in King of Prussia were sickened with Legionnaires’, reviving memories of the 1976 crisis, although both men survived. Since the discovery of the Legionella bacillus, doctors have been able to treat cases of the disease with antibiotics.

Dan Royles is Assistant Professor of History at Florida International University, in Miami. His first book, To Make the Wounded Whole: African American Responses to HIV/AIDS, is under advance contract with the University of North Carolina Press. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Wet weather spawns more Legionnaires' disease cases (WHYY, October 20, 2011)

- University employee tests positive for Legionnaires' disease (WHYY, July 30, 2015)

- Comparing New York's Legionnaires' disease outbreak to Philadelphia's experience (WHYY, August 6, 2015)

- Audio Time Capsule: The discovery of Legionnaires' disease (NewsWorks, January 28, 2016)

- 40 years after Legionnaires outbreak, the case for a 'Safe Breathing Water Act' (NewsWorks, July 22, 2016)

Links

- About Legionella (Centers for Disease Control)

- "The Philly Killer": 1976's Legionnaires' Disease (The Pennsylvania Center for the Book at Penn State University)

- Death of a Hotel: Legionnaires' Disease Kills Bellevue Stratford (St. Petersburg, Florida, Evening Independent via Google News Archive)

- Bacteria and the Bellevue: the Birthplace of Legionnaires' Disease (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- 40 Years Later, Scientist Who First Discovered Legionnaires' Disease Is Still Learning Lessons (The Pulse, WHYY)