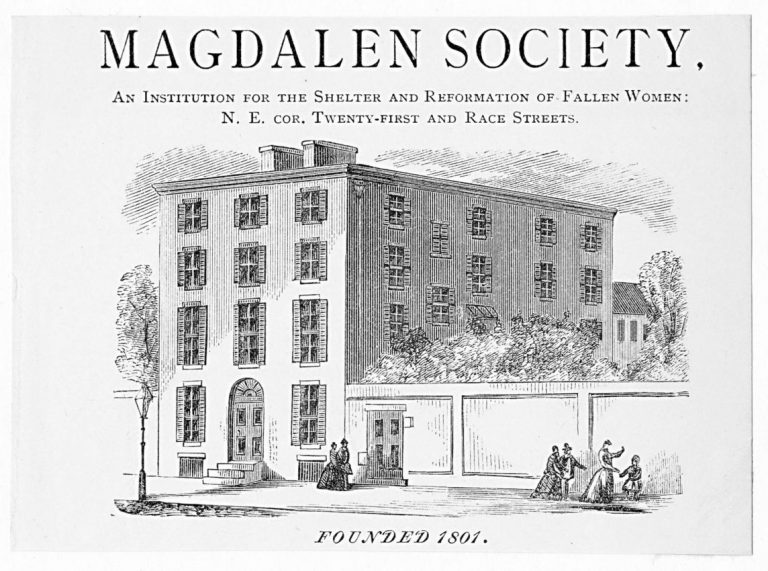

Magdalen Society

By Marie Conn

Essay

Founded in 1800, the Magdalen Society of Philadelphia was the first institution in the United States concerned with caring for and reforming “fallen women.” A good many women in nineteenth-century Philadelphia apparently preferred prostitution for a variety of reasons, notably as a means of support in order to achieve economic independence from an oppressive family or as a preferred alternative to other wage work. The Magdalen Society Asylum offered them a temporary home, seeking in the process to redeem and reform them.

The inspiration for the Philadelphia institution, which was created by an interdenominational group of Protestant religious leaders, merchants, and master craftsmen, was most likely London’s Magdalen charity of 1758 whose program combined Christian penitence, obedience, industry, and discipline.

Bishop William White (1748-1836), first bishop of the Episcopal Church of the United States as well as the first bishop of the Diocese of Pennsylvania, served as the society’s first president until his death. The society sought to help women who had strayed from the paths of virtue, and who, in the opinion of the founders, were desirous of returning to a moral life. Since the women in question, however, often did not see themselves as morally degraded, very few came and many stayed only a short time, using the asylum as a temporary, sometimes seasonal, refuge. In line with the temper of the time, pregnant women and African Americans were barred from its services.

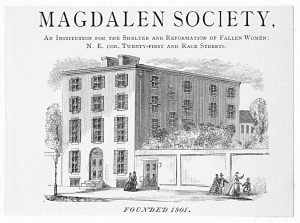

The original Philadelphia asylum was located at Race and Twenty-First Streets, a relatively isolated location designed to effectively separate the women from their former lives and identities. Eventually, the society built a high wall around the property. After a storm destroyed the original asylum in 1842, a new building replaced it several years later.

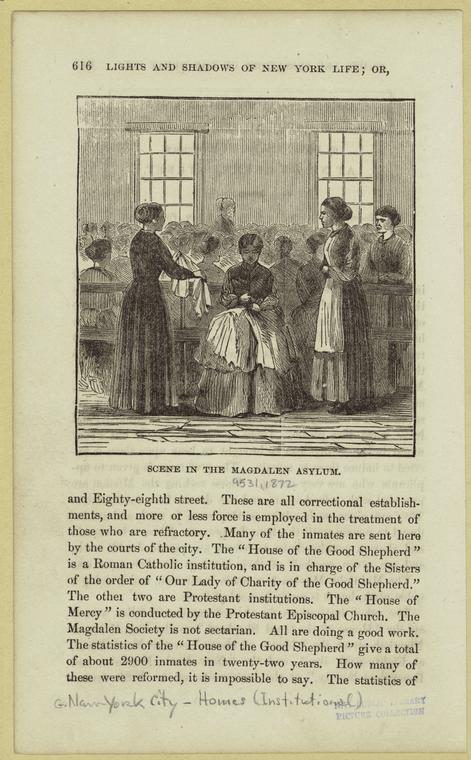

The reform program of the asylum had two components: moral guidance and skills for economic security. The daily routine thus was meant both to reform and to train. The reform came by way of daily Bible readings, worship, and time spent with visiting clergy. Asylum staff directed training to existing social structures, involving tasks like laundering, sewing, and cooking. The reformed prostitute would then be prepared to rejoin society as a domestic worker, as a laundress, as a worker in the textile trade, or as a wife and mother.

Recruiting Residents

The records of the society imply that women were “recruited,” much as prospective college students were in later times. In the beginning, there were seldom more than a handful of residents at a time. Eventually, the board of managers hired a man specifically to bring women into the home. The board also suggested to city officials that certain offenders might be sent to the asylum rather than to prison. By 1850, 925 women had passed through the asylum but, as the trustees themselves conceded, few were converted to lives of piety.

Like the changing attitudes of society itself, the Magdalen Society evolved over the years. In 1847, the Rosine Association for Magdalens was founded by women of Cherry Street Friends’ Meeting and the First Unitarian Church presided over by the Reverend William Henry Furness (1802-1896). It served as a place where delinquent young girls could be taught respectable trades. The new association took a different tack from the existing Magdalen Society, both because its founders objected to the latter’s supervision by men and because they considered its approach to be repressive. Philadelphia’s Rosines insisted on female management, both at the policy-making level and in the daily supervision of the institution, promising sympathy and the example of “respectable” women to the inmates. The Rosine Association determined that the “girls” needed marketable skills and training in household management, so their approach included education and even some free time, with no emphasis on moral regeneration.

In the 1870s, perhaps in response to the Rosine movement, women also took over the leadership of the Magdalen Society. At the same time, they began to transform the asylum into a home for wayward girls and thus no longer ministered to prostitutes. They sought to transform such a girl into a healthy woman able to function as the moral anchor of a family. The society sheltered, cared for, and educated these girls. Vocational training became an integral part of the society’s programs. Religion was still important but, since the emphasis was now on prevention rather than reform, it was not as heavily stressed.

A Move to Montgomery County

In 1914, the city condemned the Magdalen house, which forced its board to look for a new location. Facing financial difficulties and a diminishing number of residents, the board shifted its activity to the suburbs. In June 1915, residents moved to Fairview Farm in Montgomery County.

Still facing financial difficulties, the leaders of the Magdalen Society decided to change the society’s name and its mission. Accordingly, in 1918 the Magdalen Society became the White-Williams Foundation for Girls, taking its name from Bishop White and from George Williams (c. 1777-1852), a Quaker philanthropist. Its new role was to act as a clearinghouse for other institutions for girls and to work with the Philadelphia Public Schools’ Placement Bureau, subsequently the Office of Student Enrollment and Placement. In 1920, the foundation dropped “for Girls” from its name and admitted boys. In 1994, the name again changed, this time to White-Williams Scholars.

In 2011, White-Williams Scholars merged with Philadelphia Futures, a nonprofit organization providing Philadelphia’s low-income, first-generation-to-college students with the tools, resources, and opportunities necessary for admission to and success in college. So the seed planted in the 1800s in an effort to reform and educate prostitutes, Philadelphia’s “fallen women,” continued to evolve, bearing entirely new benefits in another era.

Marie A. Conn is Professor of Religious Studies at Chestnut Hill College in Philadelphia. She holds a doctorate in Theology from the University of Notre Dame. Her books include C. S. Lewis and Human Suffering: Light among the Shadows, and Noble Daughters: Unheralded Women in Western Christianity, 13th to 18th Centuries. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University