MOVE

Essay

MOVE, a controversial Philadelphia-based organization often associated with the Black Power movement, combined philosophies of Black nationalism and anarcho-primitivism to advocate a return to a hunter-gatherer society and avoidance of modern medicine and technology. The group’s very loud and public quest for racial justice, as well as its strong views on animal rights, led to a number of confrontations between MOVE members and their West Philadelphia neighbors as well as with Philadelphia police. The most famous of these confrontations, in 1985, earned Philadelphia a reputation as “the city that bombed itself.”

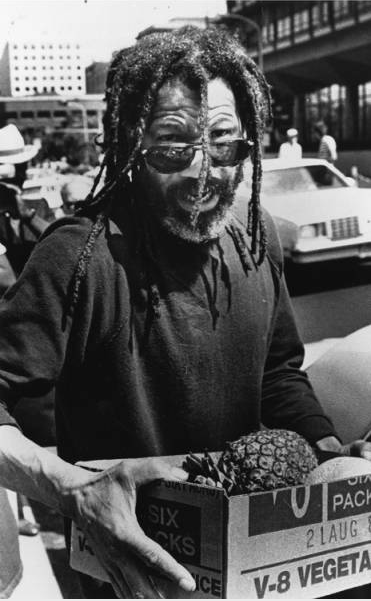

MOVE emerged in the early 1970s as the American Christian Movement for Life or the Christian Life Movement. Vincent Leaphart (1931-85), who later took the name John Africa, founded the group and wrote the foundational document initially known as The Book of Guidelines, The Book, or The Guidelines and eventually called The Teaching of John Africa. Because Leaphart was functionally illiterate, he turned to Donald Glassey (b. c.1946), a social worker from the University of Pennsylvania, to help him write and edit the document, which included roughly three hundred pages. This manifesto espoused the importance of self-reliance and a nature-based lifestyle that included scavenging, composting, eating raw foods, and exercise. Ultimately it called for a return to nature even for those who lived in the city. Since the founding of the group in 1972, MOVE members have lived communally primarily in West Philadelphia, with additional properties in Rochester, New York.

The first major confrontation between MOVE and the police led to a shootout in Powelton Village on August 8, 1978, that left police officer James J. Ramp (1926-78) dead and nine MOVE members in jail for life. The incident began when police arrived to execute a court order requiring the group to vacate a compound they had created at 307-309 N. Thirty-Third Street after repeated complains from neighbors concerning the number of animals being kept on the property, reports of filthy conditions, frequent use of a bullhorn to transmit lectures based on John Africa’s teachings, weapons code violations, the presence of children in reportedly filthy conditions, and MOVE’s refusal to pay gas and water bills. Shooting erupted, and Ramp was hit in the back of the neck. MOVE was blamed for his death, but accounts of MOVE members stated that Ramp was facing the home at the time of the shooting, leading to questions of whether the bullet could have actually come from a MOVE weapon. Five firefighters, seven police officers, three MOVE members, and three bystanders were also injured during the standoff.

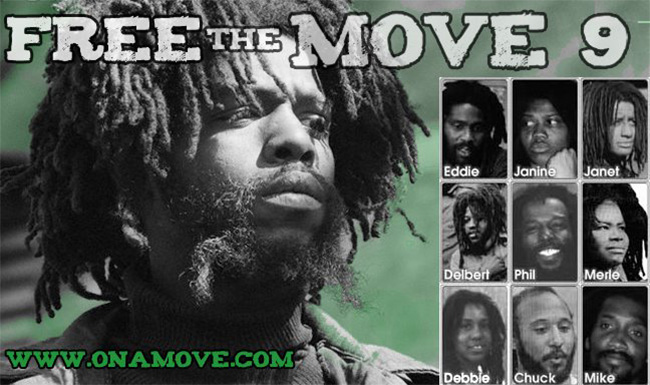

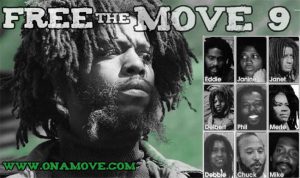

The arrested members, since known as the MOVE Nine, were sentenced and convicted of third-degree murder in Ramp’s death. They became eligible for parole in 2008, but all were denied then and in subsequent hearings. MOVE Nine members included Merle Africa (1951-98), who died in prison in 1998 at the age of 47; Phil Africa (1956-2015), who died in prison in 2015 at the age of 59; and Chuck (b. 1959), Michael, Debbie (b. 1956), Janet (b. 1951), Janine, Delbert, and Eddie Africa (b. c.1947).

Bullhorn Broadcasts

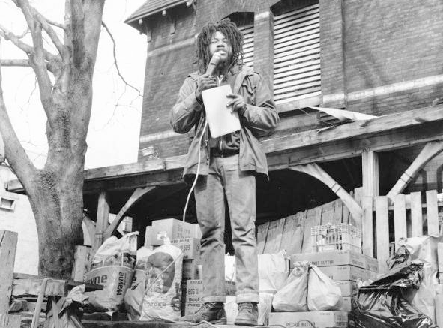

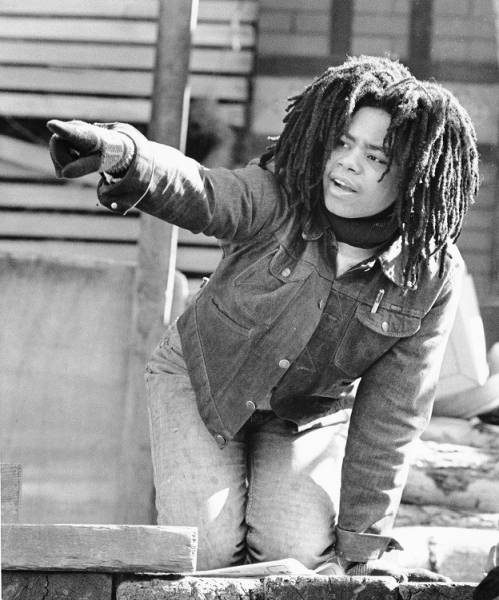

After the confrontation at Powelton, MOVE relocated to 6221 Osage Avenue, in the Cobbs Creek area of West Philadelphia, a predominantly African American and middle- class neighborhood. Determined to force their neighbors to hear their case and join their efforts to free the Move Nine, MOVE members broadcast their message night and day through a bullhorn from their fortified headquarters. They built what was essentially a fortress within the Osage home, adding bunkers inside the house and on the roof. They also kept many animals—from domesticated dogs and cats to wild rats—in the home, leading neighbors to complain of filth and health risks to both the MOVE children and to the neighborhood in general. Observers noted young children who were not enrolled in school. Some neighbors also complained of verbal and physical assaults committed by MOVE members and garbage being piled up around the home. As a result, District Attorney Edward Rendell (b. 1944) issued arrest warrants and Mayor Wilson Goode (b. 1938) sent the police to execute the warrants on Monday, May 13, 1985.

As police and city officials had anticipated, MOVE members refused to respond to the officers who arrived or to send the children out of the home. The mayor and Police Commissioner Gregore Sambor (b. 1928) saw this as justification to use military-grade weapons and extreme measures, despite the presence of the children. Announcing over a loud speaker, “Attention MOVE: This is America!” Sambor began the attack by sending in a team to flush the house with fire hoses. When MOVE remained unresponsive, officials blew holes in the walls to fumigate with tear gas. That did not work either, and a shootout ensued. After shooting thousands of rounds into the MOVE compound, police decided to use explosives to knock the bunker off the roof, using a Pennsylvania State Police helicopter to drop high-powered C4 explosives onto the house. The explosives caused a fire, accelerated by the presence of gasoline in the home. Fearing that firefighters could get caught in the crossfire between police and MOVE members, officials let the fire burn and it spread throughout the neighborhood as area television crews filmed the destruction. Danger from crossfire also kept MOVE members pinned inside the home. Some eyewitness reports indicated that when MOVE members finally tried to exit the burning house, police fired on them, but controversy remained over this claim. The conflicting reports, along with the live television coverage of much of the day’s events, led many people in Philadelphia and elsewhere in the United States to question the decision-making process of the mayor and other officials.

The bombing of the MOVE compound killed six adults and five children and destroyed more than sixty homes, leaving more than 250 Philadelphians homeless. Only 13-year-old Birdie Africa (1971-2013), who later took back his given name of Michael Ward, and Ramona Africa (b. c.1955) survived the confrontation. Those killed included children Katricia Dotson (Tree), Netta, Delitia, Phil, and Tomasa Africa and adults Rhonda, Teresa, Frank, CP, Conrad, and John Africa (1931-85).

Mayor Goode quickly appointed a committee to investigate the bombing. The commission’s report, issued on March 6, 1986, concluded that police used “grossly negligent” tactics and committed an “unconscionable” act by “dropping a bomb on an occupied row house.” The commission expressed doubt that police would have acted similarly in a white neighborhood. Although the commission called for grand jury investigations, nobody was prosecuted and in 1987 Goode won reelection. In 2013, Philadelphia Police Commissioner Charles Ramsey (b. 1948) requested a Justice Department review of the city’s use of force, and that review’s conclusions echoed the MOVE Commission Report, finding systemic deficiencies and problems with improperly trained police using military equipment against citizens.

Ramona Africa and the Aftermath

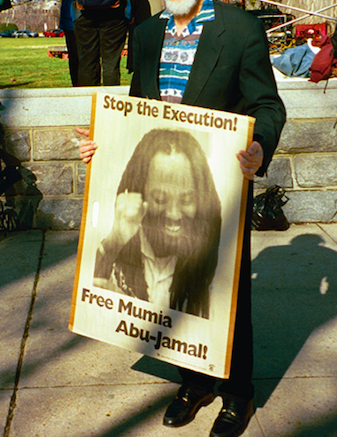

Ramona Africa served as her own attorney in a trial that ultimately led to her conviction on riot charges. She served seven years in prison. In 1996 she and relatives of two MOVE members who were killed in the bombing sued the city and won a total of $1.5 million in a civil suit judgment ordered by a federal jury. She continued to serve as the spokesperson for MOVE and to advocate for the release of the MOVE Nine and Mumia Abu-Jamal (b. 1954), a Black radio journalist who had covered the MOVE Nine trial before his own controversial conviction in the shooting death of a Philadelphia police officer in 1981. Michael Ward was placed in his father’s custody and spent years in therapy to deal with his experiences with MOVE and the bombing. He drowned in a hot tub on a cruise in 2013.

The neighborhood surrounding the Osage home never fully recovered from the bombing. A home at 6221, built to replace the MOVE compound, stood vacant in 2016. With four bedrooms, one bathroom, and 2,203 square feet, it was valued at approximately $54,119. Sixty-one homes were rebuilt by developers hired by the city, but they were almost immediately plagued by problems such as leaky roofs, faulty plumbing, saggy floors, inadequate electrical wiring, and peeling siding. The contractors who built the homes were sent to jail for mishandling funds, but some residents felt they had no choice but to accept the hastily and poorly rebuilt substitutes for the homes they lost. In the early 2000s the city finally agreed to buy the homes for $150,000 each, leading to a mass exodus of residents, many of whom had been part of the neighborhood for generations. Those who remained continued to emphasize that theirs is a safe and close-knit community within walking distance of Cobbs Creek Park.

In November 2016, thirty-one years after the conflagration, the City of Philadelphia issued a request for proposals to develop three dozen properties that had been vacant since the buyout of 2000.

The MOVE bombing gave Philadelphia police the distinction of having carried out the only aerial bombing against U.S. citizens on U.S. soil. The incident and the later state of the neighborhood, which the city failed to adequately rebuild, continued to serve as a testament to police brutality and institutional racism in Philadelphia. In 2016, Ramona Africa compared the MOVE bombing to the police killings of Black men throughout the U.S. in later years. Tying MOVE to the Black Lives Matter movement, she asserted that cases of police brutality are “happening today because it wasn’t stopped in ’85.”

Beverly C. Tomek is the author of Pennsylvania Hall: A ‘Legal Lynching’ in the Shadow of the Liberty Bell (Oxford University Press, 2013) and Colonization and Its Discontents: Emancipation, Emigration, and Antislavery in Antebellum Pennsylvania (NYU Press, 2011). She earned a Ph.D. in history at the University of Houston and teaches at the University of Houston-Victoria. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- 'Birdie Africa,' child of MOVE, dies at 41 (WHYY, September 25, 2013)

- New MOVE documentary is riveting, painfully accurate (WHYY, October 31, 2013)

- Seared into city's memory, MOVE tragedy holds lessons that still resonate (WHYY, May 13, 2015)

- Thirty years on, TV reporter recalls covering MOVE bombing (WHYY, May 13, 2015)

- Philly moves to sell houses rebuilt after MOVE bombing in '85 (WHYY, November 17, 2016)

- Site for marker memorializing MOVE bombing still not pinned down (WHYY, June 19, 2017)

- After 40 years, Debbie Africa of MOVE Nine released from prison (WHYY, June 18, 2018)

- As Philly honors former mayor with street sign, protesters assail Goode's MOVE legacy (WHYY, September 21, 2018)

- Last member of MOVE freed on parole in death of officer (Associated Press via WHYY, February 7, 2020)

- Former Mayor Goode: Philly must apologize for MOVE bombing 35 years ago (WHYY, May 11, 2020)

- Philly releases independent report on city's mishandling of MOVE bombing victims' remains (WHYY, June 9, 2022)

- MOVE supporters gather in Cobbs Creek, 40 years after deadly bombing by Philly police (WHYY, May 14, 2025)

Links

- "On a MOVE" (website of MOVE)

- John Africa's MOVE Organization (World History Archives)

- MOVE Commission Report (Temple University Library)

- The Disrespectful Handling of the MOVE Victims' Remains by the City and Penn Merits More Investigation (Philadelphia Inquirer)

- Independent Lens: Let The Fire Burn (PBS)