National Colored Convention Movement

Essay

During the antebellum period, when Philadelphia was home to one the North’s largest free African American communities, the city’s Black leaders launched the national Colored Convention movement to address the hostility, discrimination, exclusion, and violence against African Americans by whites in northern cities. As national forums, the national Colored Conventions held from 1830 to 1864 brought together African Americans to debate and adopt strategies to elevate the status of free Black people in the North and promote the abolition of slavery.

The racial tensions in northern cities in this era can be attributed to Black migration from the South and the abolition of slavery in the North, which dramatically increased the free African American population in the early nineteenth century. Many whites viewed blacks as an economic threat, a burden for state and local poor relief agencies, and a source of crime.

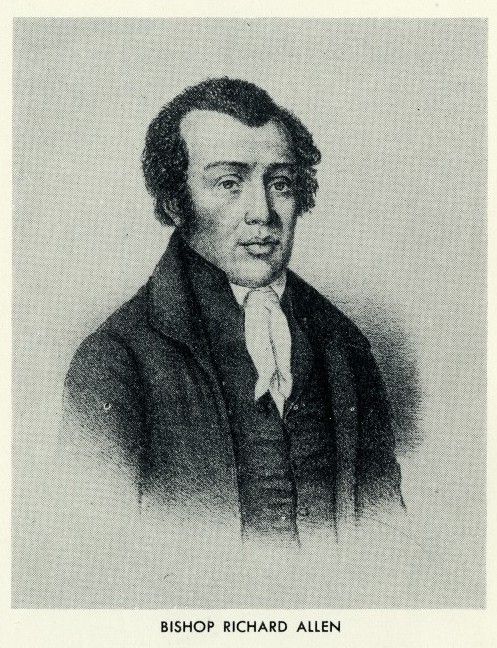

The idea for a national Colored convention first emerged among Black leaders in response to events in Cincinnati, Ohio, during the late 1820s. Following Cincinnati’s enforcement of Ohio’s “Black laws” in 1829 and subsequent violence unleashed by white mobs against the city’s Black community, in the spring of 1830 Hezekiah Grice (1801-?), a Baltimore activist, appealed to African American leaders throughout the North to devise a plan for emigration to Canada. His appeal went unanswered for several months until Richard Allen (1760-1831), minister and founder of Mother Bethel A.M.E. Church in Philadelphia, called a national meeting of Black leaders to address this issue.

Plans for a Settlement in Canada

The delegates who gathered in Philadelphia at Bethel Church from September 20-24, 1830, selected Allen as president of the newly formed American Society for Free Persons of Color. The purpose of this organization was to establish a settlement in Canada, viewed as preferable to the United States because of its lack of institutional racial discrimination, similar climate, and shared language with the United States. (Canada later fell out of favor among most blacks in part because of white hostility that blacks encountered and their conviction that they were due rights in the United States.) Before returning home from the 1830 Philadelphia meeting, though, delegates adopted a resolution that called for a general convention the following year in Philadelphia, thus launching the national Colored Convention movement.

In addition to the first gathering in 1830, Philadelphia hosted the conventions in 1832, 1833, 1835, and 1855. Guided by middle- and upper-class Black delegates, the conventions adopted a philosophy of respectability centered on education, temperance, and thrift. Black leaders believed this strategy would dispel popular stereotypes that portrayed African Americans as lazy, ignorant, and susceptible to vice. By demonstrating economic independence and success, convention delegates hoped that whites would see Black people as responsible and productive citizens worthy of equal rights. They also believed that respectability would lead to greater support for immediate abolitionism among moderate white reformers. Delegates also used the egalitarian rhetoric of the American Revolution, arguing that slavery and discrimination were incompatible with the nation’s founding documents.

Although strategies of respectability and moral persuasion dominated, a younger generation of activists in the 1840s and 1850s began to endorse more militant solutions. Black nationalism was one option, a controversial position that called for African Americans to establish a separate colony in Africa, the Caribbean, or Central America. Many Black Philadelphians rejected this strategy, believing that respectability and interracial cooperation were the best route to ending slavery and securing equality.

A Stronger Collective Voice Emerges

Launched during an important period of Black political activism, the national Colored Convention movement created a stronger collective voice among African Americans and a forum for devising national strategies to confront the growing racial hostility. Although the convention movement did not end slavery or gain equal rights for African Americans, by the outbreak of the Civil War some other notable goals were achieved. Delegates established manual labor schools that trained a number of blacks in skilled trades. The convention also created the American Moral Reform Society (1835-1841), an organization headquartered in Philadelphia and led by local businessmen James Forten (1766-1842) and William Whipper (1804-1876). This group attempted to uplift Black communities through education and promoting moral behavior such as temperance. The conventions also united African American communities from across the country into a national network of political activism. Finally, delegates formed a coalition with radical white antislavery activists to oppose movements such as the American Colonization Society (ACS), an organization with ties to slaveholders that encouraged free Black people to relocate to Africa.

During the Civil War the convention delegates began to devise plans for the post-war Reconstruction period. At the October 1864 meeting in Syracuse, New York, delegates created the National Equal Rights League, a national forum to replace the Black convention movement, and lobby the federal government for full citizenship rights for all African Americans on the premise of Black service in the Union Army and the notion that all men were created equal. With numerous state and local chapters, the league’s members became active in northern and southern politics. Members of the Pennsylvania State Equal Rights League lobbied members of Congress to ratify a constitutional amendment in support of Black male suffrage. The league successfully pressured the Pennsylvania Republican Party in ratifying the Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, while also continuing to demand protection of their civil and political rights in a new era in which white hostility increased and federal and state support for protecting Black rights waned.

Lucien Holness is a Ph.D. student at the University of Maryland-College Park. His research interests include African American and Atlantic history. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University